Pepper Trail ’75, PhD ’84, never knows what might land on his desk. Take the time that Trail—senior ornithologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Forensics Laboratory in Ashland, Oregon—found a Styrofoam takeout container in his office, wrapped in evidence tape and sent by one of the service’s 250 special agents nationwide.

Trail in his Oregon office, where he works on about 100 cases each year and processes some 1,000 pieces of evidence.Tom Fowlks

Inside was a tiny roasted poultry breast on toast, garnished with parsley and mustard sauce. The agent wanted to know if Trail could identify the meat’s source—and he soon confirmed that it was an American woodcock, a game bird that restaurants can’t legally serve. Trail’s work led to a raid of a Vermont eatery where more than 100 frozen woodcock breasts were discovered. “When I first took this job I was a little concerned that it would become boring,” he says. “But that has definitely not been a problem.”

Described by National Geographic as the “Sherlock Holmes of bird crimes,” Trail has spent the last two decades helping the federal government investigate wildlife trafficking, habitat destruction, and other offenses involving avian victims. He doesn’t hunt down crooks or go undercover; instead, his responsibility at the lab—the only one in the world dedicated to crimes against wildlife—is to provide scientific assistance to those who enforce federal laws protecting threatened and endangered species or mandating conservation measures. The work can be gruesome: Trail is usually called on to identify a species from partial remains. To make an identification—which often plays a key role in bringing charges for such crimes as international smuggling and illegal hunting—he scrutinizes the anatomical features of recovered bird parts, sometimes with nothing more to go on than a single feather or talon. Though many of the experts with whom Trail shares the 40,000-square-foot forensics facility use cutting-edge technologies, his methods are decidedly old school. Says Trail: “The highest-tech tool I use is a microscope.”

Each year, Trail takes part in about 100 cases and handles more than 1,000 pieces of evidence. That means he’s seen a lot of unusual—and upsetting—things over the years, from poisoned bald eagles to artwork made with hornbill skulls to necklaces crafted from cassowary toes. He once testified in court as an expert witness against a man accused of smuggling songbirds to New York from Guyana; there’s a black market for the birds, called towa towas, among Guyanese immigrants who bet on them in singing contests. More recently Trail has been disturbed by a thriving trade in love charms made from dead hummingbirds—known as chuparosas—that are smuggled in from Mexico. For Trail, the daily procession of remains can be hard to take. “All birders have a ‘life list’ of the birds they’ve seen in their life, but I also have a death list,” he says. “It’s now over 800 species.”

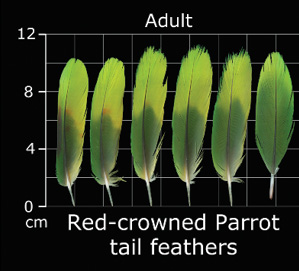

A page from the online database he established to help identify feathers of North American birds.Feather Atlas

To ease the uglier aspects of the job, Trail writes poetry in his spare time. He has published three collections, one of which was a finalist for the 2016 Oregon Book Award. He’s also heartened by another accomplishment: the creation of the Feather Atlas, the first online database for identifying feathers of North American birds. The website—which now includes almost 400 species and had 1.5 million visitors in 2018—is used by law enforcement, birders, teachers, and artists. “It’s become a much more widely used and appreciated resource than I ever thought it would be,” Trail says.

Raised on a 100-acre farm in Upstate New York, Trail fell in love with birding as a boy and majored in biology in the College of Arts & Sciences. His doctoral thesis in CALS took him to Suriname, where he studied the mating behavior of the Guianan cock-of-the-rock, a tropical bird whose males boast striking orange feathers and a dramatic, semicircular head crest. After doing postdocs at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and the California Academy of Sciences he served as a senior wildlife biologist in American Samoa for two years before relocating to Ashland, where his wife had gotten a job as a pediatrician. In 1998 the forensics lab asked him to fill in after its only ornithologist left; what was supposed to be a temporary position proved to be a vocation. Now sixty-five and planning to retire by the end of 2020, he has trained another forensic ornithologist to succeed him. “I consider this job ethically important, and it gives me a lot of satisfaction,” he says. “It directly aids the survival of the birds that I love so much.”