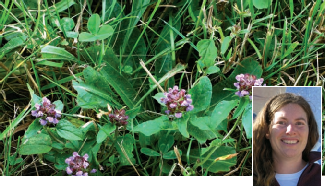

Nancy Gift, PhD '02, pleads the case for 'plants out of place'

Nancy Gift, PhD '02, pleads the case for 'plants out of place'

Come spring, Nancy Gift, PhD '02, liberates the manual push mower from her garage and sets to work tending her half-acre lawn in the Pittsburgh suburbs. Despite her enthusiasm for the chore that doubles as a summertime exercise regimen, Gift rarely plots a straight course across the yard. A love of weeds—from creeping violet to goldenrod—guides her path. This time of year, she steers clear of the mountain bluets, a clumping relative of the gardenia bearing pale blue blossoms on eight-inch stems. Later in the summer, hawkweed—a perennial relative of the sunflower—gets a pass. "I get excited about leaving something audacious in the front lawn," she says, noting that every so often, her husband uses the family's gas-powered mower to tame the effect. "The nature of weeds is totally individual."

As a graduate student in crop and soil sciences on the Hill, Gift memorized the common and Latin names of hundreds of weed species, learning to identify them in their earliest stages of growth, all the better to eradicate them with uniquely tailored herbicidal cocktails. Today she campaigns for the preservation of what she calls "plants out of place," the mosses, wildflowers, and dandelions that suburbanites battle with an arsenal of carcinogenic chemicals. "I end up advocating organic lawn management because people are not willing to read the small print on herbicide labels or learn how they differ from one another," she says, recalling an Ithaca neighbor who wore only shorts and tennis shoes when treating his lawn. "A farmer has to have a license and learn something [to legally apply herbicides], but homeowners don't."

This winter, St. Lynn's Press released Good Weed, Bad Weed, a wire-bound, laminated guide, complete with full-color photos of forty-three species common throughout the Northeast, Pacific Northwest, and Canada. It's Gift's latest salvo in her campaign for a gentler approach to lawn care. Her first book, A Weed by Any Other Name, was published in 2009. Subtitled The Virtues of a Messy Lawn, or Learning to Love the Plants We Don't Plant, the light-hearted collection of essays is a paean to the weeds of Gift's youth in the hills of Kentucky, a meditation on the hazards of indiscriminate chemical use, and a chronicle of her efforts to make peace with both the weeds of Pittsburgh and neighbors who don't necessarily share her aesthetics.

Gift may have subtitled her latest book Who's Who, What to Do, and Why Some Deserve a Second Chance, but the Chatham University assistant professor of ecology has her limits. She despises crab-grass and musters little more than grudging respect for multiflora rose, despite the Vitamin C-rich hips she savors in tea. While one chapter of A Weed by Any Other Name details the joy of home-brewed dandelion wine shared with fellow graduate students, another recounts how, in one of her first acts as a new homeowner, she wielded a bottle of Roundup to eradicate the poison ivy vining its way up a hedgerow where her two daughters play. In Good Weed, Bad Weed, which also offers recipes for the edibles common to lawns, Japanese knotweed serves as a stand-in for rhubarb in a strawberry pie and garlic mustard features in pesto—but culinary redemption wasn't enough to bump the two invasives from the category of the condemned. "My publisher was surprised because I included recipes for them, but neither deserve a second chance," she says. "When I take them to eat, there's a sense of vengeance."

For her dissertation, Gift investigated whether quackgrass, a perennial weed ubiquitous in agriculture throughout the Northeast, could be maintained as a cover crop in corn fields, reducing herbicide use and coaxing value from the plant. "The idea behind her research was, this weed isn't all bad," says her former adviser, crop and soil sciences professor Russell Hahn. "If we could learn to manage it, we could prevent erosion, reduce runoff, and suck up nitrogen that might be left over from the growing season." Gift's nuanced approach to assessing the thresholds at which individual weed species cause harm or create value makes as much sense for homeowners as it does for farmers, says Hahn. "I get upset when people say they're going to eradicate a weed," he says. "It's almost impossible and probably unnecessary."

Soon after the publication of A Weed By Any Other Name, the author received the latest notice from her daughters' school about upcoming herbicide and pesticide applications. She didn't like what she read: plans to spray the lawns with a chemical implicated in both childhood leukemia and breast cancer. Her protesting e-mails went viral, and the school adopted a one-year pilot plan to go herbicide free. "A couple of the parents who got involved ended up making me sound reasonable," recalls Gift. "They didn't want anything sprayed, ever. It made my approach of saying, 'Let's look at the label and the toxicity,' seem sane."

— Sharon Tregaskis '95