Margaret Weiterkam, PhD ’01, at the Smithsonian’s Moving Beyond Earth exhibit.

Margaret Weitekamp, PhD ’01, holds a doctorate earned under eminent historian Richard Polenberg. She has taught women’s studies at Hobart William Smith. She’s the author of an award-winning scholarly book published by Johns Hopkins University Press. And there she was: trying to figure how to get a 14,000-pound space shuttle engine into the Smithsonian without cracking the floor. “I sat through hours of meetings about exactly how much weight would be on any one wheel of the frame; how much weight is required for the tug that can pull the thing or the forklift that can lift it; what’s the combined weight of the engine, the stand, the forklift, the crane, and the truck; and whether it would break the end of the museum to put it on our terrace,” Weitekamp recalls with a laugh. “It’s an interesting application of one’s historical training to, on the one hand, be a publishing researcher, and on the other hand try and figure out, ‘Is there a door big enough?’ “

Weitekamp is curator of the National Air and Space Museum’s Social and Cultural Dimensions of Spaceflight Collection—essentially, the historian in charge of the museum’s pop culture holdings. She’s responsible for some 4,500 objects—both actual historic artifacts, like medals and mission patches, and objects from the world of science fiction, from a Flash Gordon ray gun to a Buzz Lightyear toy to comic books based on “The Jetsons,” War of the Worlds, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The huge engine is part of the museum’s Moving Beyond Earth exhibit, which features not only rarefied holdings like astronaut gear and a twelve-foot-high model of the space shuttle, but mass-market items such as a shuttle-themed bath toy, puzzle, and kids’ sneakers. Such things, she explains as tourists mill about the gallery, can put the evolution of human space flight into cultural and historical context. “The idea of putting wings on a spacecraft or having one that takes off like a rocket and lands like an airplane didn’t suddenly show up in the Seventies,” Weitekamp says, pointing out a vintage depiction of a rocket at the exhibit’s entrance. “You can look back to the Twenties and Thirties—Buck Rogers’s ships were winged spacecraft that were used over and over.”

A self-confessed “closet space and science fiction nerd” since childhood, Weitekamp was six years old when Star Wars came out in 1977—what she calls “exactly the right age.” She played with toys from the movie; her brother even had Star Wars curtains from the Sears catalog. “I loved imagining what it would be like to go into space,” she recalls. “In some ways that’s part of what I do now—think about how the ways people have imagined space flight relates to what is actually possible.” On the Hill, she was Polenberg’s last graduate student—”At some point,” she says, “it became clear that I needed to finish so he could retire”—and taught freshman writing seminars on science fiction. Her dissertation, on a selection program for female astronauts in the Fifties and Sixties, eventually became a book entitled Right Stuff, Wrong Sex, published by Hopkins in 2004, the year she joined the Smithsonian. She has also written a kids’ book on Pluto and co-edited a volume on the aesthetic culture of science and technology, contributing an essay on how the space shuttle is interpreted as a toy. (It gets shorter and rounder, with infantile features, sometimes even sporting a smiley face.)

Weitekamp’s job is a hybrid: in addition to designing exhibits—and wrangling with such dilemmas as how to deal with the clashing reds in the U.S. and Soviet flags for a 2007 show on the fiftieth anniversary of the space age—she is an actively publishing scholar and does outreach to schoolchildren and the media. Currently, she’s working on an overhaul of the museum’s venerable Apollo exhibit, set for 2018 or 2019. “The challenge is always, ‘show it, don’t tell it,’ ” she says. “The joke is that, left to our own devices, curators would paste our books on the walls, complete with footnotes, and have everyone read them in order. An exhibit is a different way of telling a story; it needs to be something you learn from but you don’t just read, and that people don’t always do in order. Historians are linear thinkers, but museum visitors bounce all over like ping-pong balls.”

Arguably the most famous sci-fi item under Weitekamp’s purview is located not in the exhibition galleries but in the museum’s final frontier: the hinterlands of the basement gift shop. There, behind Plexiglas—past the junior space suits and the astronaut ice cream and the zero-gravity pens—is the eleven-foot-long studio model of the starship Enterprise, used in the original “Star Trek” series from 1966 to 1969. “People have this vision of what the Enterprise looked like when they saw it on a cathode ray tube in the Sixties, with that glowy Technicolor,” she observes. “This is both impressive in size and in the sense that it’s the real thing—but sometimes fans also feel, Really? That’s it?”

The model is primarily made of painted wood, which breathes—necessitating three restorations over the years. Its curatorial file runs some 1,000 pages. “Why do we have imaginary spaceships in the middle of the nation’s foremost collection of real airplanes and spacecraft?” Weitekamp muses. “Because many of the people who were inventing and flying the actual spacecraft and airplanes were fans of imagining what it would be like, and because there’s a complex relationship between one’s ability to imagine going into space and the real ability to build that kind of a program. One of the things that we at the museum do is not just preserve the hardware of ‘the first, the fastest, and the farthest,’ but tell the broader story of how aviation and space flight have transformed America and the world.”

Science fiction, Weitekamp notes, has traditionally been a mirror of its time—current concerns about racial and income inequality, for example, are reflected in dystopian fare like Elysium and District 9—and the original “Star Trek” was a prime example. “In addition to a vision of a spaceship that can go from star system to star system, you had a bridge crew that was mixed sex, racially integrated, international, and included an alien,” she says. “In 1966, in the middle of the civil rights movement and the second wave of the women’s movement, you had this powerful vision of racial and gender integration. That has long-lasting consequences—not only culturally but in people’s real lives, for being able to visualize what’s possible.”

Big Red Rovers

Smithsonian hosts show on Mars explorers

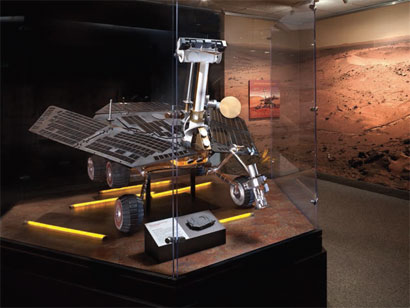

Mars Rover

Through mid-September, the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum is hosting an exhibit marking the tenth anniversary of the Mars Rover mission—including Cornell’s contributions to the project. A team led by astronomy professor Steve Squyres ’78, PhD ’81, designed, built, and outfitted the scientific instrumentation for the twin rovers, which landed on Mars in January 2004. While Spirit was disabled by the Red Planet’s harsh weather after more than six years of service, Opportunity is still going a decade later. “Our rovers were built by people like me who were inspired by space missions, both human and robotic, back in the Sixties and Seventies,” says Squyres. “If Spirit and Opportunity can provide the same kind of inspiration to others, then that’s as important a part of our legacy as our discoveries are.”

Highlights of “Spirit & Opportunity: 10 Years Roving Across Mars” are available online at airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/mer.