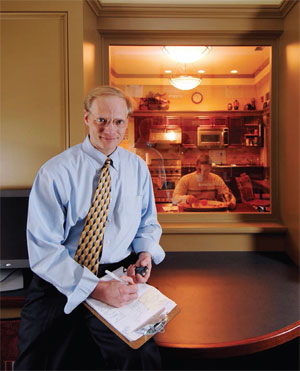

Play with your food: Marketing professor Brian Wansink in the lunchroom at an Ithaca-area elementary school.

Offer most kids the choice between apple slices or French fries, and odds are they’ll go for the greasy goodness. But what if you first ask them to ponder a philosophical question: Which would Batman choose?

To fuel his crime-fighting adventures around Gotham City, many kids allow, the Caped Crusader would take the healthier option. Could contemplating that fact inspire them to do the same?

Marketing professor Brian Wansink showed as much a couple of years ago, with a small study published in Pediatric Obesity. He and his colleagues worked with twenty-two campers aged six to twelve over the course of a month, exploring how their choices of a fast-food side dish changed after considering what their role models, such as superheroes, would eat. And indeed, the researchers found that invoking Batman and his compadres quadrupled the number of kids who went for the apples—a switch that cut nearly 200 calories out of each meal.

If your family eats fast food once a week, Wansink’s lab calculated, getting your kids to eschew the fries could keep each of them from gaining three pounds a year—no small achievement in the midst of a childhood obesity epidemic. And even better: to get the little ones on board, you don’t have to lecture them on good nutrition. Just leave it to Batman.

Through the looking glass: A one-way mirror in the Food and Brand Lab offers a view of a testing room complete with high-end kitchen.

That’s the study’s lesson, the moral to its story. And with Wansink’s work, there’s always a lesson. The mantra in his Food and Brand Lab is to create “news you can use”—practical strategies to promote healthier eating. “We will never begin to publish anything unless there is news you can use that can make someone’s life better,” says Wansink. “We’re all about easy changes you can make. It’s always focused on a single takeaway. If we can’t find a takeaway, we won’t even promote it. We might publish it in a journal, but we don’t want somebody saying”— his voice rises to a high, absurdist warble—’Well, there’s kind of a relationship between talking to your kids about their weight and how much they weigh, but we’re not even sure what it is.’ We’re not going to do that, because then we lose our reputation for having solutions.”

On a chilly afternoon last semester, Wansink and two postdocs are discussing that very subject: the potential connection between how much a young girl’s parents talk to her about her weight and how much she weighs later in life. They’ve collected data and surveys from women aged twenty to thirty-five, asking them to recall the extent to which their parents were fixated on their weight—be it too high or too low—and their eating habits. “We’re trying to figure out the relationships, partly so we can make suggestions to people as to how to approach talking to their daughters,” Wansink explains. “We’ve got journals interested in this paper, but our takeaway isn’t so punchy and impressive that we even like it. They say it’s enough of a contribution that they may want to publish it, but it’s not up to our standard of really having the impact we want. So now we’re taking it in some weird directions and seeing if we can uncover something.”

‘We will never begin to publish anything unless there is news you can use that can make someone’s life better.’ Wansink and his students are meeting in a lab space that’s part conference room, part dream kitchen. There’s the usual long table, chairs, and flat-screen TV—but at the far end of the room are cherry cabinets, a granite countertop, sink, stainless-steel refrigerator, and high-end stove. Plus, there’s another unorthodox element: a pair of one-way mirrors. The room serves as a testing and observation space for the lab’s many studies on food choices—colorful, often unorthodox experiments that have made Wansink a media darling. “Brian is a really strong marketer of the science that he completes,” says former postdoc Lizzy Pope. “One of the problems we have as researchers is that we do great studies and they just kind of die in the scientific journals because most people can’t access them or even understand them. Brian is published in well-respected, peer-reviewed journals, but he’s really good at translating his results into practical tips that you can actually use, and getting that information out to the general public.”

Wansink has been featured in the New York Times, USA Today, the Atlantic, ABC News, NPR, “Good Morning America,” CNN—just about every media outlet you can think of, and many that you can’t. (A Google News search on him brings up, among more than 200 other results, a mention of his work in a column on emotional eating from the Wallowa County Chieftain of Enterprise, Oregon.) Arguably, he’s the most widely known, media-savvy Cornell professor since Carl Sagan. “I spent a year freelancing, and it gave me a real appreciation of all the people who say no to you,” admits Wansink, who holds a master’s in journalism and mass communication from Drake University as well as a PhD in consumer behavior from Stanford. “I told myself, ‘I will never say no to the smallest newspaper or the most inexperienced reporter.’ Even student journalists get five minutes.”

‘My work is so weirdly fringy,’ Wansink admits. ‘Most people who are superstars in their field want to stay in the dead center of it.’Wansink’s offbeat experiments—many of which he detailed in his first book, Mindless Eating (2006)—are catnip to readers and reporters. There’s the now-infamous bottomless soup bowl caper, in which he demonstrated the awesome power of the “clean plate” phenomenon. His lab rigged bowls to keep refilling with tomato soup as the subjects ate—leading them to put away 73 percent more than controls eating from regular vessels. And what’s more—as the article’s abstract in the journal Obesity Research noted—the diners “did not believe they had consumed more, nor did they perceive themselves as more sated than those eating from normal bowls.” Ouch.

Then there was the study that was published under the title “Bad Popcorn in Big Buckets.” For that one, Wansink and his grad students surprised moviegoers with free popcorn, either in medium or large containers. The catch: it was five days old and had the texture of Styrofoam. But his unsuspecting subjects munched the stale snacks anyway, even though a lot of them had just eaten lunch—and they put away even more if it came out of a giant tub. “Did people eat because they liked the popcorn?” Wansink muses in Mindless Eating. “No. Did they eat because they were hungry? No. They ate because of all the cues around them—not only the size of the popcorn bucket, but also other factors . . . such as the distracting movie, the sounds of people eating popcorn around them, and the eating scripts we take to movie theaters with us. All of these were cues that signaled it was okay to keep on eating and eating.”

Wansink cheerfully admits that his academic path has been a bit tortuous, if not torturous. He traces his research interests to growing up in Iowa, in a home where money was sometimes tight; his mom kept an extensive vegetable garden to help feed the family and supplement their income, and took extension courses to learn canning and preserving techniques. “I grew up selling vegetables door to door,” he recalls. “And some places I’d stop, they’d buy everything in my wagon—and at the very next house, identical in every regard, they’d look at me like I had kryptonite.” The conventional wisdom was that healthy eating was a matter of education and income—but Wansink sensed there was something more complex at play. Years later, as a grad student, he wanted to do research on why some people eat their vegetables and some don’t. It didn’t go over well with his advisers. “They said, ‘This is ridiculous,'” he mimics with a chuckle. “‘You’re not going to study that stuff. You’re going to study something theoretical.'” He eventually landed his dream job on the marketing faculty at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business—but his career hit a speed bump when he was denied tenure in the mid-Nineties. (Again, his area of interest got little love from the powers that be; as he recalls it, the takeaway was, “Nobody’s interested in food.”) He was teaching at Penn’s Wharton School when he was offered tenure at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign; he notes with a wry laugh that when he asked Wharton to make a counteroffer, they essentially said: best of luck to you.

He came to Cornell in 2005; its practical, land-grant ethos, he says, is a perfect fit. “My work is so weirdly fringy,” Wansink admits. “Most people who are superstars in their field—whether they’re in consumer behavior, psychology, behavioral economics, or nutrition—want to stay in the dead center of it. They don’t want to work with a strange, fringy thing that’s too overlapping.”

Blond, blue-eyed, and very fair, Wansink looks like he could be Conan O’Brien’s long-lost brother—and he’s got some of the TV host’s manic energy, gift of gab, and comedic flair. When he talks about using corporate-style tactics to get kids to eat better in school lunchrooms, for instance, he channels a pitchfork-wielding villager from a monster movie. “A lot of people will say, ‘There shouldn’t be any branding or marketing in schools, because”—again, his voice rises to a comic warble—“it’s evil! Evil, I tell you!‘” He goes on to add: “But we did this study that said, ‘Who really benefits most from branded items in schools?’ It’s not cookies and candy, because everybody wants those anyway. If you put Elmo on something, it’s going to have a much bigger impact on carrots. In fact, it triples how many carrots kids buy.”

In Mindless Eating, Wansink detailed myriad strategies for consuming fewer calories without thinking about it. (Another of his mantras: “It’s easier to change your eating environment than to change your mind.”) As he notes, every day we make more than 200 eating decisions. Since constant virtue is both exhausting and unrealistic, the best strategy is to set yourself up to make the right choices. Among his many tips: switch to smaller dinner plates, since they make it seem like you’re getting a bigger portion; leave serving dishes on the counter rather than the table, so you have to make a conscious effort to get more food; never eat straight out of a container, like a bag of chips; and serve caloric beverages in tall, skinny glasses, since his research has shown that even professional bartenders pour too much into short, wide ones. “Life is so hard already,” observes Pope, the former postdoc. “When we’re asking people to make hard eating choices, it’s almost like they don’t have enough willpower left over from all the decisions they have to make in every other area of their lives.” With Mindless Eating-style tactics, she says, “people think, OK, I can do that, because it’s not going to test me every day.”

On the tray: In the wake of new USDA regulations, school lunches have become a focus of Wansink’s work.

In his new book—Slim by Design, which comes out in late September—Wansink expands the concepts to encompass what he calls one’s “food radius.” More than 80 percent of what you and your family eat, he writes, is dictated by five main venues: your home, your workplace, your favorite grocery store, your go-to restaurants, and your children’s schools. The book describes, for example, the Food and Brand Lab’s work on improving eating habits in school lunchrooms via relatively minor changes. Want to get kids to take more fresh fruit? Put it in an attractive, well-lit bowl in at least two locations, one of which is near the cash register. To encourage them to eat their veggies? Rebrand them as “X-ray Vision Carrots” or “Superman Salad.” To give students a sense of pride and ownership in their lunchroom? Put up banners naming it after the school mascot (i.e., the “Bobcat Café”). To promote white milk over chocolate? Rather than an outright ban—which can make kids feel alienated and deprived—put the white out front and move the chocolate to a more inconvenient location, so it’s up to them to decide whether to bother getting it. “Brian calls them ‘low-cost, no-cost’ changes,” says Alison Nathanson ’14, a former applied economics and management major who served as a TA for Wansink’s Food and Brand Lab Workshop course, which gets roughly five times as many applicants as there are spots. “They help the students eat healthier without even knowing that they’re doing it.”

Nathanson, who grew up outside New York City, got involved with the lab the spring of her freshman year and went on to TA for four semesters; after graduation, she landed a marketing internship at a tech company. Pope, who recently joined the faculty at the University of Vermont after a year in Wansink’s lab, praises him for making mentoring a priority even amid his packed schedule. “Brian really cares about the people who work for him—he really wants them to be successful,” she says. “With someone like him, who’s a superstar in his field, it’s hard to know what you’re going to get; sometimes you meet these big scientists and, frankly, they’re not that nice. But Brian is incredibly caring.” And she points out that working in a lab with so much going on—the constant media requests, the many studies, the varied research topics—was its own learning experience. “This is a really high-powered lab, and Brian runs at quite a high frequency,” Pope says. “For me, just watching that has been really informative—being exposed to all these different projects and this ‘go-go-go’ mentality of, ‘Where’s the next place we’re going to make an impact?’ “

In the late Aughts, Wansink took a two-year leave from Cornell to lead the USDA’s Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, which unveiled new federal dietary guidelines in 2010; the following year, based on that work, the agency released an overhauled version of the “food pyramid” dubbed MyPlate. School lunches have become a major lab focus, as Wansink has helped the USDA assess the impact of the new federal regulations released in 2012. He and behavioral economics professor David Just created the Smarter Lunchrooms Movement, which offers advice on best practices—like the well-positioned fruit bowl, or crafting restaurant-style names (say, “Grandma’s Roasted Chicken”) for healthy entrees. Former postdoc Drew Hanks, who recently took a job at Ohio State University after three years in the lab, worked on an ongoing project to assess waste in the wake of a mandate that every lunchroom tray have a fruit or vegetable, whether the student wants it or not. “The lab is very open to new ideas—that’s what’s so exciting about it,” Hanks says. “It has high expectations as far as publishing is concerned, but there’s a lot of support. There is always a new project to work on, always new ideas to kick around and discuss.”

And the investigations aren’t just conducted by grad students and postdocs; Wansink has long involved undergrads in research, which has been a University priority in recent years. As a sophomore, Nathanson got to spend a day single-handedly revamping the lunchroom at an Ithaca elementary school, making changes and reporting the results. “You’re learning how to put yourself in the consumer’s point of view, whether it’s for profit or not,” notes Nathanson. “Brian’s not trying to sell anything—he’s trying to get people to eat healthier—but you have to think the same way.”