A novel approach to Arabic integrates the 'glorious' with the everyday; Man of Conviction; Speed Kills; Beer Nut; Good Vibe; Mixed Media; Dress for Excess

A novel approach to Arabic integrates the 'glorious' with the everyday

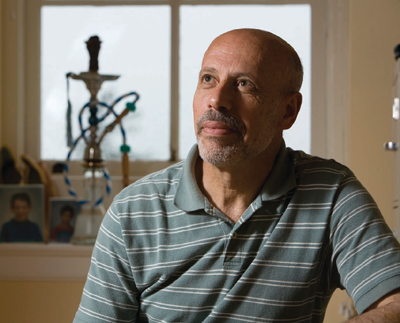

It's the quintessential scene in crime fiction: the hard-bitten cop interrogates the lowlife perp. In just about any language, the dialogue would likely be laden with expletives, the characters speaking in the gritty patois of the street. But in a modern Arabic novel, notes Munther Younes, both detective and suspect would sound as though they were speaking the equivalent of Elizabethan English. "The artificial, bookish language throws me off immediately," says Younes, a senior lecturer in the Department of Near Eastern Studies. "I can't relate to it."

That disconnect exemplifies Arabic's diglossia—the existence of two distinct but interrelated forms of a language. One is written and read; it's the formal language of the Qu'ran, literature, journalism, business, diplomacy. The other is the colloquial tongue, spoken in varying dialects around the world. "Structurally they are different," says Younes. "Ninety percent of words are shared by the two, but pronounced differently. The best way to illustrate it would be that once you pick up a pen you think in terms of formal language, and once you pick up the phone you speak in the conversational." Students in Western universities traditionally spend years studying the formal version before being allowed to learn the other, but the Palestinian-born Younes sees the bifurcation as a waste of time—and an inevitable source of frustration. "The formal language is not spoken conversationally by anyone," says Younes. "When students go to Arabic-speaking countries, they find that people laugh at them, because it's like they're speaking Shakespeare's language with all the 'thous' and 'thees.' "

Younes is the architect of a novel approach to Arabic instruction, integrating the two forms from day one. With Arabic speakers and translators in ever-greater demand, Younes's system promises to impart fluency faster and more efficiently than traditional classes. "Student enrollment has increased dramatically since 9/11, and it continues," says Rosemary Feal, executive director of the Modern Language Association. "It's important to have a method to learn not only the traditional language, but also the language spoken on the ground." According to an MLA survey, the number of students in Arabic classes nearly doubled from 1998 to 2002, from about 5,500 to 10,600; in 2006, the survey's most recent year, enrollment had risen to nearly 24,000.

Formal Arabic 'is like speaking Shakespeare's language with all the "thous" and "thees." 'Younes has authored two textbooks on his method, which he calls unique to Cornell. (Although other schools use his texts, he says, they're doing so within the context of traditional Arabic instruction.) "It's quite an exciting new approach," says President David Skorton, who took a series of hour-long tutorials with Younes over the course of a year. "There's some considerable discussion of this approach, because it's quite a departure from other ways of teaching Arabic."

Near Eastern studies chair Kim Haines-Eitzen notes that the method not only challenges long-established pedagogy, but asks fundamental questions about the nature of the language itself; as such, she says, it was bound to spark some tension. "What you can find with Arabic is an elevation of the written and read form as 'true Arabic'—it's the glorious written and read language, and the colloquial is 'just dialects,' " she says. "They're often looked down upon, as opposed to seeing Arabic as a living language that people use on a daily basis." Arabic studies, she says, "is a very entrenched discipline."

Haines-Eitzen attended Younes's Arabic classes for two years—not in an official role, she says, but "purely for my own enjoyment." The professor of Judaism and Christianity grew up in Nazareth and speaks Arabic at what she describes as a third-grade level. "Sitting in on Munther's classes was like returning to the language of my childhood," she says, calling his method a much more natural approach. "If you grew up in the Middle East, you would be speaking Arabic at all times, but you'd also be learning the written and read forms. There wouldn't be an artificial divide between the two." Plus, she says, it's a better way of addressing students' needs. "They want to be able to go to Damascus or Beirut and start meeting people, speaking with people, getting around, and they can do that much more quickly with this program."

Skorton's own Arabic skills went public in May, when he wowed the crowd at the Doha Ritz Carlton during commencement for the first class of MDs from Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar. He offered a lengthy greeting in Arabic to the emi-rate's first lady, Her Highness Sheikha Mozah Bint Nasser Al-Missned, in what was reportedly a quite respectable accent. "He's a very attentive student, very serious. He really wants to learn," Younes says of Skorton. "He would be a great student of Arabic, if he just had a little more time." (Skorton strongly emphasizes that he is in no way fluent, though he can hold simple conversations. "I'm probably at the level of a ten-month-old," he says.)

Starting in the fall of 2009, the University will offer a year-long intensive course using Younes's method, funded as a four-year pilot program by $900,000 from an anonymous donor. The course, the only one of its kind in the U.S., will comprise a semester on campus— students will be in class about four hours a day, five days a week—with the spring semester at Jordan's Hashemite University. Like the rest of Younes's classes, it will employ a variety of teaching materials—not only a poem written in the formal language, say, but also a song performed in a dialect. Such integration, he says, makes for a much livelier classroom. "When I want to chat with my students casually, I hesitate to use the formal language, so I switch to English most of the time," he says. "Whereas with the conversational one, it's natural and easy. There's no affectation. The student-teacher interaction is more normal, and we can introduce things like jokes and humor— which are not actually appropriate for the formal language."

— Beth Saulnier

Man of Conviction

As case director for the Innocence Project, Huy Dao '97 vets an avalanche of letters from prisoners claiming injustice

Founded in 1991 by lawyers Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld, the New York City-based Innocence Project is a group of nonprofit legal clinics that examine cases in which DNA evidence could potentially exonerate prisoners who have been unjustly convicted. With a staff of eight, Huy Dao is on the organization's front line, reading letters from convicts appealing for help.

Cornell Alumni Magazine: How much mail are you getting these days?

Huy Dao: Averaging over the last two years, we have about 250 new requests every month. As of now, we have close to 7,000 cases that are in some stage of evaluation.

CAM: Does it weigh on you to have such power over these prisoners' lives?

HD: It can be overwhelming and depressing. The joke around the office is that someday I'll sue them for therapy. But knowing that some clients have been exonerated, you realize how important the work is. I don't particularly feel like reading about rape and murder all day, but when I walk out the door, I know I've done something good.

CAM: How did you join the Innocence Project?

HD: I was kind of angry and politicized coming out of college. I had worked in Jansen's dining hall for four years, which opened my eyes to a lot of class issues. But it was also the music I was listening to, the friends I hung out with, what I was learning in class. So I started applying to nonprofits, figuring that while I had this energy I should put it to use.

CAM: And you became assistant director right out of Cornell? HD: That was my title, but I was the second rung on a two-rung ladder, so I wasn't directing anybody. The job entailed evaluating the cases of people writing in with claims of innocence to see if they applied to the project's mandate. When I started, I had three mail bins full of letters.

CAM: What's your process for answering them?

HD: First we evaluate the case to see if it can be resolved by

DNA. If it might be, or if we don't have enough information, we send the defendant a questionnaire about defense and prosecution theory, as well as what evidence was collected, what might be tested, what documents they have, who represented them, things like that.

CAM: Why did the project choose DNA as its standard?

HD: It's a level of investigation that can be done from one place but still have nationwide scope. We can't go out and interview all of the witnesses in any given case, in any given jurisdiction. With DNA we can locate the evidence, have it tested, and do the litigation without putting resources on the ground.

CAM: Do you pursue every claim?

HD: It would have to be explicitly outside of the mandate for me to reject it. For example, if someone wrote, "I have a drug possession case. It was baking powder and not cocaine," then that's not going to be settled by DNA. But I was trained to err on the side of generosity. The mandate is simple: if there is a way for post-conviction DNA testing to prove innocence, then we will look at the case. For a long time, most of our cases involved sexual assault, because those are more likely to have biological evidence. But as the technology has gotten better, we're opening our doors to cases where, twenty years ago, you'd have no idea that DNA testing could resolve innocence.

CAM: For example?

HD: One case involved the shooting of a Boston police officer. The perpetrator fled and went into a house, demanded a glass of water, drank it, and left some clothing behind. By testing clothing left at the shooting scene, clothing at the house, and the rim of the glass, we were able to prove that it wasn't Stephan Cowans, the guy who had been convicted of the crime and served six years in prison. I point out that story because it's not a sexual assault—it's not even blood, which is what most people think of when they think of DNA testing. It shows the power that this technology can have to right wrongs.

CAM: Do you remember the first case you followed from letter to resolution? HD: I remember the first two—one was a child rape and one was a false confession case in Pennsylvania, about fifteen minutes from where I grew up. I was surprised by my own reaction. What you usually see is people walking out with their hands in the air, celebrating. But for me, it was an overwhelming sense of relief that the case had not slipped past.

CAM: Has your job required you to go into prisons?

HD: I went to the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola to visit clients. I don't really remember what it was like, it was so overwhelming. The other prison I went to was in Pennsylvania, to collect a DNA sample. I got there after lunch, and I was struck by how the lighting and the smell were exactly like my high school. I walked past the cafeteria and it smelled like Tater Tots. The architecture was kind of the same, even the seating in the cafeteria. I took the sample in the infirmary, and it looked like a nurse's office in any suburban Pennsylvania school. That was quite shocking.

CAM: Since the prisoners' requests all come via the written word, has your English degree helped in your work?

HD: I went on to get an MFA in poetry at the New School, and I think that both degrees have informed me as far as looking at shades of meaning and context— you have to weigh lucidity, literacy, and various forms of desperation. Language becomes something else when someone is blindly reaching out for help, often without hope that anything is going to happen.

CAM: Is your poetry ever inspired by your day job?

HD: Very little of it, actually. I find that writing about what I do makes for over-wrought pieces that are really only interesting to me.

CAM: How has this work shaped your view of the criminal justice system?

HD: I don't know how anyone can not see that the system is fraught with potential for human error. As much as race and class shouldn't affect a system that is designed to be fair, we see that they do— both in targeting an investigation and in rates of incarceration. People are always asking me questions like, "How many innocent people are in prison?" I don't know, but there are over two million people in prison, and if 1 percent are innocent, you have tens of thousands. A 1 percent error rate—which would be good in any other system—is very disturbing.

CAM: How do you view the current debate over administration of the death penalty?

HD: Death penalty cases are so complex, I don't know that there has ever been a fair treatment in the mass media of what the issues really are. In talking about it, people aren't separating the moral outrage, "an eye for an eye"—the reasons why the death penalty might exist—from how the death penalty exists. It's the highest-stakes realm of a very flawed system. I don't want to live in a state that would consider the execution of an innocent person the cost that society has to bear for the death penalty to exist.

CAM: Are there any particular cases that haunt you?

HD: Every day, but I try not to obsess on any single case because the vast majority that come across my desk I have to reject, simply because they don't meet the mandate—but that doesn't mean that their innocence claims are any less true. And so the mass of them sticks with me. Not knowing, and not being able to provide a means of ever knowing, weighs on you every day.

– Beth Saulnier

Speed Kills

Lab of O aims to protect right whales

There are only 350 to 400 right whales left in the North Atlantic—and each year, as many as forty die from being hit by ships. But since January, the whales have had a chance for safe passing during part of their yearly migration between Maine and Florida, thanks to a network of sixteen high-tech buoys placed along shipping lanes in Massachusetts Bay. Designed by bioacoustics experts from Cornell's Lab of Ornithology, the buoys have underwater microphones that listen for the call of a right whale and send the information every twenty minutes to the Ithaca lab for analysis. If the calls are confirmed to be from a right whale, the ships' captains are immediately notified and required to slow down ten knots. "We know that when the ships go fast, whales have no chance to get out of the way," says Christopher Clark, director of the lab's Bioacoustics Research Program, which also studies the calls of birds and elephants. "Now we've implemented a technological solution."

Clark and his team had been implanting listening devices in the ocean around New England for ten years to gather information on whale migration patterns and behavior. The chance to use that technology for conservation came in August 2006, when a company called Excelerate Energy, bidding for permission to import liquefied natural gas, agreed to fund the whale-alert project in exchange for the right to use the port of Boston. Currently, only Excelerate ships and those from one other firm are mandated to slow down, but Clark and his team hope that other companies will sign on. "At this point," he says, "the collaborative relationship is just starting."

— Jenny Niesluchowski '10

Beer Nut

Dan Mitchell's stein overfloweth

The aroma Dan Mitchell '00 remembers best from his microbrewery's early days is not that of yeast or barley or hops. It's the distinct fragrance of a 1987 Subaru station wagon, Ithaca Beer Company's first delivery vehicle. "You'd turn on the heat and it smelled like a squirrel's nest," Mitchell recalls. "It was brutal, but it's what I had." The Subaru could hold only a few kegs, its back bumper dragging en route to Ruloff's and other Ithaca bars. "There was no one else moving the beer around," Mitchell says. "It was me."

What a difference a decade makes. Now wholesalers lug truckloads of the suds to bars and restaurants in four states. The company is marking its tenth anniversary this year, and it has two extra reasons to celebrate: its "birthday" beer, Ten, won first prize as the state's best craft-brewed beer at the 2008 Tap New York festival, and Ithaca Beer Company (IBC) was crowned the state's best craft brewery. Drinkers seem to agree. IBC has averaged about 25 percent growth each year since tapping its first keg in 1998. "Something's working right," Mitchell says. "I'm not complaining."

The company is riding the wave of several trends in the beer world. Like many other independent craft brewers— which the trade defines as ones that produce fewer than 2 million barrels annually and are not owned by industrial beverage behemoths like Anheuser-Busch—IBC is capitalizing on its small-town roots by using local ingredients and cranking up the variety, flavor, and alcohol content. "We're not overly flashy," Mitchell says. The company's Double IPA (India pale ale) uses 100 percent New York State hops and has twice the alcohol of its other beers. Apricot Wheat—its best seller, with about 45 percent of total sales—has a fruity finish, while coriander and lemon zest spice its Partly Sunny. Ten is a pumped-up version of IBC's slightly bitter CascaZilla ale, but with more hops and alcohol and a touch of smoked malt for a little bite. The company also makes artisanal root beer and ginger beer. "They aren't breaking any barriers and doing crazy, wild stuff," says Lew Bryson, managing editor at Malt Advocate magazine. "But the crazy, wild stuff is less than 1 percent of the craft-beer market. The beers that people drink the most are the kinds that Ithaca is making. When I go into a bar, that's the kind of beer I'm going to have three of."

For Mitchell, business came before beer. "I was always the kid on the corner with the lemonade stand," he says. He got into a fistfight at age six because his buddy kept swilling their product. "I said, 'If you drink it all, then what are we going to sell?' It was the only fight I was ever in." A self-described "horrible student," he dropped out of Hobart College after two years, unsure of his future. He came into his own in California, where he climbed the ladder—literally—at an organization that trains students to manage painting companies. In two-and-a-half years, Mitchell went from painter to district manager for Northern California, training fifteen managers to run their own territories. "It was a crash course in learning how to run a business," he says. "I was excelling at it, I liked it, and I had to do every aspect. That was a major transition for me."

He planned to finish his degree at Berkeley, but his sisters in Ithaca convinced him to apply to Cornell. "I figured I was a long shot," Mitchell says. "But Cornell liked what I had done with my time off." While bartending one night, he overheard a couple of customers wondering why the city didn't have its own brewery. "Microbrews were fairly new, but we were selling a lot of them," he says. "Light bulbs went off, and I said, 'That's a great idea.' "

Eventually, Jeff Conuel '92 took over the brewing while Mitchell focused on sales. 'We'd bottle together,' Mitchell says, 'and then I would throw it in my truck and start going store to store, bar to bar.'He left Cornell (his wife, Mari Rutz Mitchell '98, MS '03, would eventually convince him to return and graduate), and with a partner contracted a Chicago brewery, developed a dreamy logo modeled on Cayuga Lake, and started peddling. Six months later, customers complained when they learned that Ithaca Beer was made in Chicago. His partner quit. And then the brewery shut down. "I decided I might as well learn how to brew and just do this myself," Mitchell says. He spent a year apprenticing at a pub in Peterborough, Ontario, 300 miles from Ithaca—far from future competition. "Every weekend I'd drive up there and brew," he says. "Then I'd come back here—tend bar, paint houses, whatever. Eventually I raised the money and knew the craft." Soon Jeff Conuel '92 took over the brewing, while Mitchell focused on sales. "We'd bottle together," he says. "And then I would throw it in my truck and start going store to store, bar to bar."

Nationwide sales of craft beer have increased by 58 percent since 2004, while overall beer sales have remained nearly stagnant, according to the Colorado-based Brewers Association. "The local guys are growing faster than the national brands that have more name recognition," says Paul Gatza, the association's director. That's because of the low quality of so-called industrial beer made by the likes of Budweiser, Miller, and Coors, Mitchell says. "It's like the American beer market has set us up [for success]. They've convinced the audience that American beer is this dumbed-down drink."

In the past few years IBC executive brewer Jeff O'Neil has come up with a high-end, experimental line called Excel-sior, named after the New York State motto meaning "ever upward." The line includes three types of ale: White Gold, a rustic pale wheat; Old Habit, a barrel-aged rye; and Brute, a golden sour ale. They're the kind of new styles that puzzled wholesalers ten years ago. "They weren't actively looking for small breweries," Mitchell says. "Then they'd come back and say, 'That beer you're making in your basement—I hear it's pretty good.' "

— Susan Kelley

Good Vibe

Hospitality plus rock & roll equals one grad's dream job

John Resnick sips a Coke in a corner booth of a coffee shop called Maryjanes, which is itself in a corner of the Hard Rock Hotel in San Diego. Over the chorus of the Ohio Players' 1975 hit "Love Rollercoaster," the 2007 graduate of Cornell's master's program in hospitality management contemplates the hardest thing about his job: "explaining what I do."

Resnick is the vibe manager, a title only found at Hard Rock hotels—the sort of overtly hip properties where atmosphere is everything. "The best way for me to describe my job is that I'm in charge of music and culture," says the twenty-six-year-old Manhattan native. "But really it's the entire guest experience— the content on the video wall behind the front desk, the music, the smells, but also how that experience translates to our employees, how they act, and what they can tell you about the brand."

In other words, Resnick spreads the gospel of Hard Rock. On this Sunday morning in May, which happens to be his day off, he sure has dressed the part. Clad in True Religion jeans, with leather bracelets on his wrists, a chunky, biker-style silver chain around his neck, and an elaborate tattoo on each bicep, he looks like an indie rocker. But looks can be deceiving. "I've pretty much come to understand that I don't have any musical talent," he says, while a tune by Jane's Addiction rocks from the coffee shop's sound system. "In my apartment, I fool people all the time. I have a guitar. I have turntables. But I have no talent."

But he did grow up with a passion for music, greatly influenced by his stepfather, a writer and musician who once lived next to Bob Dylan and the Band in the hinterlands of Woodstock. Resnick earned his undergraduate degree in business administration from tiny Salve Regina University in Rhode Island. After a stint with a property management company, he enrolled at the Hotel school, thinking he might someday run his own bed-and-breakfast.

When Resnick heard that a Hard Rock Hotel was opening in San Diego, he snagged a two-week internship in January 2007. The property was under construction, and its managers were trying to get a sense of the local party scene. "My first assignment was to go to as many bars as I could, write reviews of them, find out bottle and drink prices, and bring in my receipts," he says. "I called all my friends and told them, 'It's official. I have the greatest internship ever.' " Upon earning his degree, Resnick was hired as a guest services manager; six weeks later, he was offered the vibe spot. "I said, 'What's the job description?' They didn't have one."

One of Resnick's primary responsibilities is music—programming every playlist from a collection of more than 15,000 songs in constant rotation in fifty-two zones of the hotel. What plays in Mary-janes, a sort of retro-yet-contemporary diner, differs from what's heard in the lobby or the elevators. "A lot of the flexibility comes in our meeting spaces," he says. "We have over 40,000 square feet of meeting space. Some groups really embrace the Hard Rock theme, so often I'm asked to make playlists for them."

If a CEO would like to surprise his employees by learning how to spin records for the company shindig, Resnick (who has befriended nearly every DJ in town) will offer some lessons. If a celebrity requires a personal concierge for the weekend, Resnick is the man. Occasionally, he'll burn CDs for hotel guests, no matter how questionable their taste— like the one who asked for a birthday CD comprising "Party Like a Rock Star" recorded over and over.

"Danny California" by the Red Hot Chili Peppers comes over the diner's speakers. "It's off the Stadium Arcadium album," says Resnick. He nods toward the door. "If you walk out and turn left, we have the jumpsuit that Chad Smith wore as a drummer while they were recording it." Resnick's favorite pieces of memorabilia at the hotel are handwritten lyrics of George Harrison's "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" and Jimi Hendrix's Fender Jazzmaster guitar. "I know every single thing about every piece we have," he says—and it's his job to make sure new employees do, too. But along with celebrating rock's past, it's also Resnick's responsibility to see into its future. "At Hard Rock, we're always trying to be on the cutting edge of music," he says. "We try to find out what's going to be big."

Resnick gets an iTunes allowance, and he attends at least one concert a week. He works with the hotel's venue manager to bring in live acts like the Black Eyed Peas, and he oversees planning for major parties, such as the hotel's massive winter wonderland-themed bash last New Year's Eve, which featured a dance floor that looked like a frozen pond. "My job is to create experiences that our guests can't get anywhere else," Resnick says, over the opening guitar lick of the Kinks' "Lola," "experiences that leave them begging for more."

— Brad Herzog '90

Mixed Media

Scrimple & Save

At Collegetown Pizza you can get a free soda; at Fontana's Shoes, you get 10 percent off your purchase; you can save $2 per wash at East Hill Car Wash. To get these and other deals, you have to present the S Card—the latest offering from scrimple.com, a site that posts discounts at Ithaca businesses, valid with a student ID.

ILR student Matt Ackerson '09 started Scrimple Inc. as a project for an entrepreneur-ship class his junior year. The site initially allowed students to print and clip free coupons; participating businesses paid Scrimple each time one was redeemed. After hundreds of coupons were printed, Ackerson decided there was enough interest in the site to try a more modern approach, so he introduced the S Card. While businesses now sign up for free, students have to purchase the card, which costs $20 per year, to take advantage of the deals. "It's the same idea as before—encouraging students to go out and be social while helping them save money—but we are now using better point-of-sale technology," he says.

Scrimple beat out nearly 150 other entries from Cornell undergrads to take first place at last year's Big Idea Competition, sponsored by Entrepreneurship@Cornell and Student Agencies; Ackerson invested most of the $2,500 prize back into the company. His future plans for Scrimple include expanding into other markets such as Syracuse and New York City, partnering with Cornell student groups seeking a fundraising tool, and introducing the Blakk Card, which can be used at bars and other nightspots. "It's only going to ramp up further next year," Ackerson says. "I've started saying I go to school on the side and run the business full-time."

— Liz DeLong

On the Slope and Online

On a typical day last spring, a visit to the slopemedia.org website offered video from a campus fashion show, a Grease-themed promo for the senior prom, student debate about the Democratic presidential nomination, and photos from a Saturday night concert by a DJ named Girl Talk. The site is home to Slope Media Group, Cornell's first student-run multimedia organization. Comprising radio, TV, and an online magazine, Slope lets users customize their media menu, choosing from both current material and archives of all its shows and articles. "It's definitely revolutionary," says president Caitlin Strandberg '10. "Even in the car, our generation is plugging in iPods. People want to self-select their music, and you can do that with Slope."

In addition to music, Slope Radio offers talk shows and Big Red sports coverage. Slope TV, broadcast both online and on CUTV (available in residence halls), covers sports, news, music, politics, and culture. Slope Magazine, currently digital, will offer a print version beginning this fall. More than 300 students are involved in Slope, Strandberg says, but its programmers can be anywhere in the world, since users can upload and edit content. Students on the New York and Qatar campuses have logged on, as have undergrads studying abroad. The organization is hoping to get alumni involved—creating, say, a Class of 1980 playlist on the radio station—and encouraging more users to contribute content. Says founder Yaw Etse '08: "I would like it to get to the point where the first thing that pops into someone's head when they record something on campus is, 'Let me throw this onto Slope Media.' "

— Chelsea Theis

A Wiki for CU

If you type "Big Red Bucks" or "Insectapalooza" into the online encyclopedia Wikipedia.org, you'll come up empty. But type them into CUWiki.org, and the information will be at your fingertips. Launched in 2007, the student-run site aims to be an encyclopedia of all things Cornell, says founder Tyler Garzo '08, a bio major who started it as an independent study. Like Wikipedia, it relies on the public to generate content. While Garzo wrote the first fifty articles (or "wikis"), the site now has more than 100—from "Dragon Day" to "Pumpkin on Clocktower"—and gets more than 1,000 unique visitors a month.

As the sole arbiter, Garzo vets all postings; he pays for the host server himself to keep the website unofficial. "It avoids risk for the University and allows CUWiki users to write more freely," he says. Garzo's favorite is the wiki on tunnels, which describes the verified (and rumored) underground routes beneath the campus. When the subject of the tunnels came up on a recent carpool trip, Garzo realized that the site had arrived. "Some of the other passengers started talking about the article as a good source of information," he says, "without realizing that I had written it."

— Chelsea Theis

Dress for Excess

Arbitrage caters to the aspiring titans of Generation Y

On the "shirts" page of Arbitrage's online clothing store, a brooding young man with five o'clock shadow gazes intently at the camera—cigar in one hand, whiskey in the other. A photo to his right depicts the tanned, toned torso of an anonymous woman, slightly sweaty, clad only in artfully placed sushi. Click through to the online "brand book" of the high-end men's haberdashery (button-down shirts run $165 to $185) and you'll find more provocative images: a man teasing a sexy blonde's lips with his forefinger, naughtily threatening her with a riding crop as he tugs her hair from above; a trio of women lounging lustily on a bed as a man videotapes them; a naked woman, photographed from behind, blindfolded by a swanky necktie. The photos, shot by fashion photographer Marc Todd, embrace the unapologetic flaunting of masculine power—a sex-drenched updating of Eighties-style conspicuous consumption à la Wall Street's Gordon Gekko.

Launched in 2007 by Alan Chan '06, Manoj Dadlani '04, and Kristin Ming '06, Arbitrage offers men's shirts for both the boardroom and the bar, as well as ties, cufflinks, and wallets, all catering to the status-conscious urbanite. Over the past year, the line has landed coveted shelf space in stores ranging from Fred Segal and Saks Fifth Avenue to Canada's GotStyle and Japan's Liquor, Woman, and Tears. The fashions have even made it onto the backs of celebrities like "Entourage" star Adrian Grenier. "It's not just clothing," says Chan. "It's about a lifestyle of success." Arbitrage caters to that ambition, with its logo—a bull—everywhere from its cufflinks to the linings of its ties.

Chan describes Arbitrage's target market as a "modern urban businessman who works hard and plays hard," which he says he can relate to; he worked for Summit Partners, a Palo Alto venture capital and private equity company, before deciding that finance wasn't for him. When he started work, Chan felt he had few options to fill his post-college closet. There was Brooks Brothers, but its clean-cut style was too conservative, catering more to men of a certain age. There were generic department store button-down shirts—but they were, well, generic. Then there were offerings from Hugo Boss, Ermenegildo Zegna, and Paul Smith, but Chan wanted something with a slimmer fit, more suitable for a twenty-something man-about-town.

Dadlani, too, was a member of Chan's target audience, having worked at the management consultancy and private equity firm Applied Value for a few years after Cornell. While Chan is technically chief executive officer and Dadlani chief operating officer, they each have their hands in all aspects of the young company. The two spend their days talking to store reps, organizing promotional events, and overseeing production at their Boston-area and New York factories. Ming, who studied textiles and apparel at Cornell, is the line's creative director, the artistic force behind the clothes. Though she expected to land her first job with a large design house—perhaps working just on accessories or sketching rough designs—Ming says she prefers overseeing products "from concept to finish" at the startup.

Arbitrage's so-called "corporate" line tends toward light-colored shirts made from luxe cottons and crisp patterns like pinstripes and herringbone, along with wide-cut ties that force a large knot, the better to make a strong statement in the boardroom. Then there's the "lounge" line, with slightly shorter, slimmer shirts meant to stay untucked. One of the company's most popular items is its $230 Krona hoodie, a mullet of a shirt with a button-down front, French cuffs, side slant pockets, and a hood. There's a summer-friendly style in seersucker, which online culture maven Thrillist says is "perfect for maintaining your rep as the hardest mofo at the yacht club."

The brand recently launched the Arbitrage EFG (Environmentally Friendly Garment) collection, made of organic materials, and is looking into more bamboo- and soy-based products. With the word "charity" embroidered on the shirts' cuffs, the wearer can casually drop into conversation that $25 from each item goes to an organization that brings safe drinking water to developing communities. After all, as Dadlani says, the lounge shirts are meant to appeal to a specific audience: "The guy who wants to pick up a girl when he's out." To that end, the company's advertising suggests that men who wear its clothes are more likely to be fighting off the ladies in a club's VIP room than chasing them on the dance floor. Playing up the lure of an exclusive lifestyle, Arbitrage made its early-stage website password-protected. The key? "Fidelio," the word that allowed entry into the erotic nightclub in Eyes Wide Shut.

— Melissa Korn