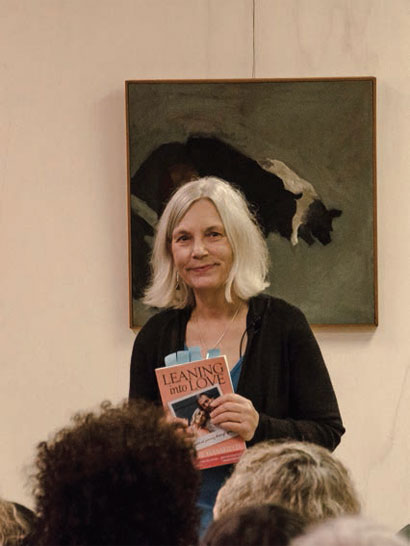

Healing process: Elaine Ware Mansfield ’67 at a reading of her memoir, Leaning Into Love. Photo: Franklin Crawford.

Elaine Ware Mansfield ’67 met the love of her life nearly a half-century ago in a motorcycle shop on Ithaca’s West End. There was a lot to like about Vic Mansfield: handsome and athletic, he was a doctoral student in astrophysics who worked at Cornell’s Arecibo Observatory. “I knew right then that he was the one,” she recalls. “I was so sure of it that I didn’t worry about chasing him. I just made it obvious.” They were married in 1968.

Three days after their fortieth anniversary, Elaine Mansfield bid farewell to her husband and best friend. After a two-year battle, Vic Mansfield, PhD ’72, succumbed to a rare form of lymphoma. He was sixty-seven, a professor of astronomy and physics at Colgate, and a practitioner and teacher of Tibetan Buddhism; his book on Buddhism and physics featured a foreword by the Dalai Lama himself.

Mansfield was at her husband’s side from diagnosis to treatment to death. Throughout that painful process, she filled dozens of notebooks with clinical and personal observations. She fashioned these and other writings into the memoir Leaning Into Love: A Spiritual Journey Through Grief, published this fall by Larson, a small press in Upstate New York. “For two years I’ve tried to save him,” she writes in the first chapter, which describes her husband’s passing. “We’ve both tried, but there are no more escape routes. After years of struggle, his gentle passage opens my heart and stills my mind. This quiet death is his last gift to me, even as I weep and whisper my goodbyes. Just after midnight, he exhales. I wait for an inhalation that does not come.”

Mansfield’s account can be brutal in its honesty. She’s candid about moments of exasperation and resentment that overwhelmed her as primary caretaker, and the stress of being left behind to tend a house on seventy-plus acres “when I didn’t even know how to use the tractor.” There are warm moments, too, including a tender scene of marital intimacy. Throughout, Mansfield’s memoir serves as a primer on the transformative power of grief. “This honest, heartfelt first book is the story of how Mansfield lived, survived, and triumphed with her pain, told in an authentic voice by a woman who values human connection, spirituality, and the earth,” Joan Jacobs Brumberg, professor emerita of human development and gender studies, wrote in a review. “Her profound love for her husband is at the center of the book, but she never romanticizes the ways in which life-threatening illness produces anxiety and irritability, transforming both the minutiae of everyday life and the larger relationship of patient and caregiver. Mansfield acknowledges the gritty everyday tensions they both felt, as well as the profundity of caring for the deteriorating body of someone you love.”

When the couple met, Vic was twenty-five, three years into his doctoral program; his future wife was a senior majoring in government. They marched in anti-war demonstrations on campus and off. The Mansfields meditated together, studied philosophy and psychology together; they raised two sons and preserved the woodlands and meadows on their property, located half an hour outside Ithaca.

Mansfield—who is certified as a personal trainer and holds a degree in nutrition from Empire State College—now works as a volunteer with Hospicare and Palliative Care Services, leading support groups for the bereaved. She has held on to her sense of humor: in November, she gave a TEDx talk entitled “Good Grief! What I Learned from Loss.” She says her mix of gravitas and lightheartedness—and the upbeat presence of her chocolate Lab, Willow—serve her well. A lifelong student of Jungian psychology, she employs poetry and mythology in her bereavement work, encouraging the use of simple rituals and practical readings. She believes there are stages of grief similar to those outlined by Elizabeth Kübler Ross—denial, bargaining, acceptance, etc.—but says it’s a personal process that follows no particular course. “I tell people to come as they are,” she says. “Crying is okay here.” Mansfield encourages survivors to focus on themselves, and notes that many struggle with guilt for not having gotten over their loss and moved on. “In this culture we’re supposed to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps,” she says. “Grief is not on anybody’s clock. I still miss Vic. He’s part of me.”

Most of Mansfield’s workshop participants are female—in part because that’s how the meetings began, but also because of demographics, with women tending to outlive their male partners. But more men are joining, she says, and circumstances vary widely among the bereaved. Some lose spouses to long-term illness, others are facing sudden loss and trying to raise children on limited resources. To help them cope, Mansfield stresses self-care for body, mind, and spirit. She maintains a blog that covers simple ways to get through the dark hours: making pots of soup, going for walks and light workouts, and avoiding isolation. “I know I am a lucky person,” she says. “Watching Vic die made me want to help others. Death became my teacher, and my friend.”