This is just one article from CAM’s Summer Reading Special! Click the link to read the entire section.

Big Red Writers have penned many memorable books — including a few set at a certain university on a hill.

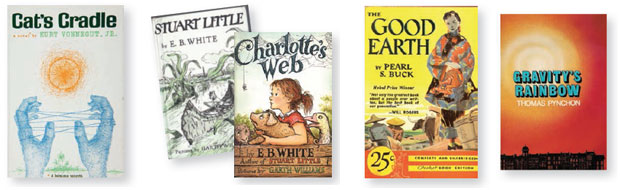

Cat’s Cradle Kurt Vonnegut ’44

Vonnegut’s most famous work—Slaughterhouse-Five, inspired by the author’s experiences during the bombing of Dresden—is the subject of this year’s New Student Reading Project. Another of his celebrated literary sci-fi novels, Cat’s Cradle (1963), also ponders the legacy of war. The book’s central allegory, a substance called “ice-nine” that can instantly freeze any living thing, was invented by a fictional creator of the atom bomb. The book’s narrator meets up with the scientist’s children, and they go on a journey to a Caribbean island nation ruled by an ailing dictator.

Charlotte’s Web & Stuart Little E. B. White ’21

White, the longtime New Yorker contributor, authored two of America’s most beloved works of children’s literature. Charlotte’s Web, published in 1952, tells the bittersweet story of a friendship between a pig named Wilbur and a spider named Charlotte, who saves him from being slaughtered through messages she weaves in her silk. As Eudora Welty wrote in a review: “As a piece of work it is just about perfect, and just about magical in the way it is done.” In Stuart Little (1945), White told the tale of a talking mouse born to human parents. Actor Michael J. Fox voiced Stuart in the 1999 Hollywood version and its 2002 sequel.

The Good Earth Pearl S. Buck, MA ’25

“It was Wang Lung’s wedding day.” So begins Buck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1931 novel about the lives of a farmer and his wife, whose fortunes rise and fall in their village in pre-World War I China. A fixture on middle- and high-school English curricula, Buck’s novel went back on the bestseller list in 2004, when Oprah Winfrey included it in her book club. A 1937 film version won two Oscars—including a Best Actress nod for Luise Rainer as Wang Lung’s long-suffering wife, O-Lan—and was nominated for Best Picture.

Gravity’s Rainbow Thomas Pynchon ’59

Winner of the National Book Award for fiction, Pynchon’s dense and complex four-part postmodern epic clocks in at nearly 800 pages. Its title refers, among other things, to the trajectory of a German V-2 rocket; its plot—if that is indeed the appropriate term—defies easy summary. To quote the original New York Times review from 1973: “Gravity’s Rainbow is bonecrushingly dense, compulsively elaborate, silly, obscene, funny, tragic, pastoral, historical, philosophical, poetic, grindingly dull, inspired, horrific, cold, bloated, bleached, and blasted.”

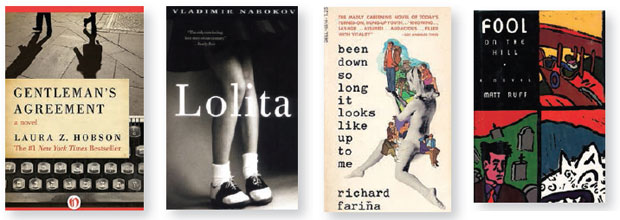

Gentleman’s Agreement Laura z. Hobson ’21

While the 1947 movie version, starring Gregory Peck, is arguably better remembered than the novel—it won three Oscars, including Best Picture—the book was both a runaway bestseller and a critical darling when it was published that same year. The plot concerns a journalist who, tasked to do a series of magazine stories on anti-Semitism, decides to experience it firsthand by pretending to be Jewish. “Abrupt as anger, depression plunged through him,” Hobson writes in the book’s opening lines. “It was one hell of an assignment.”

Lolita Vladimir Nabokov

Nabokov was teaching Russian literature on the Hill when he wrote his 1955 masterwork, which the Modern Library put at number four on its list of the 100 best novels of the twentieth century. Shocking in its—or, in fact, any—day, it follows a middle-aged scholar sexually obsessed with a twelve-year-old girl. “She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock,” Nabokov wrote. “She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.” Hollywood has filmed it twice: a 1997 version (with Jeremy Irons as narrator Humbert Humbert) and a now-classic 1962 release directed by Stanley Kubrick and starring James Mason, Shelley Winters, and Peter Sellers.

Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me Richard Fariña ’59

Fariña died in a motorcycle accident just two days after the 1966 publication of his first novel, which he wrote while a student on the Hill. Now a cult classic, it’s set at a thinly disguised Cornell—dubbed Mentor University—and features numerous local characters and landmarks. Its protagonist, one Gnossos Pappadopoulis, goes on a trippy trip through the counterculture in his college town. “Not that this is a typical ‘college’ novel, exactly,” Thomas Pynchon, a friend of Fariña’s, wrote in his introduction to the paperback edition. “Fariña uses the campus more as a microcosm of the world at large. He keeps bringing in visitors and flashbacks from the outside. There is no sense of sanctuary here, or eternal youth. Like the winter winds of the region, awareness of mortality blows through every chapter.”

Fool on the Hill Matt Ruff ’87

Publisher’s Weekly summed it up handily when the book debuted in 1988: “This exuberant first novel unfolds at Cornell University, the alma mater of its twenty-two-year-old author, who has re-imagined his school as the center of a violent and funny modern-day fairy tale. Stephen Titus George is a young writer longing for true love and a great story to tell. With the mysterious appearance of Calliope, a sorceress who can transform herself into anyone’s vision of female perfection, both of his dreams begin to come true. Ruff shapes an adventure for his protagonist that includes everything from poisoned apples to winged dragons, all set on a campus where there isn’t a professor in sight and where the actions of dogs, cats, and invisible sprites are as meaningful as those of the students.”

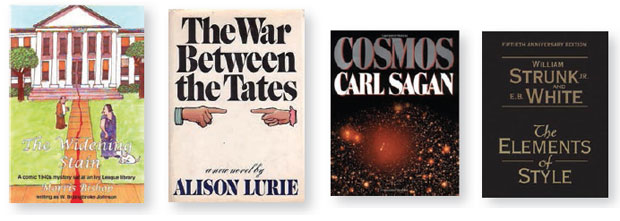

The Widening Stain Morris Bishop 1913, PhD ’26

Best known on the Hill as the author of the original History of Cornell, Bishop also penned a definitive history of the Middle Ages, reviewed books for the New York Times, and published light verse in the New Yorker. His sole foray into mystery—a comic novel released in 1942 under the pen name W. Bolingbroke Johnson—centers on the murder of a French professor found dead in a fictional version of Uris Library’s ornate reading room. While Bishop winkingly denied authorship throughout his lifetime, he did cop to it—obliquely—in a limerick he jotted in a copy shelved in Olin: “A cabin in northern Wisconsin / Is what I would be for the nonce in, / To be rid of the pain / of The Widening Stain / and W. Bolingbroke Johnson.” Rue Morgue reissued the novel in 2007 under Bishop’s byline.

The War Between the Tates Alison Lurie

Lurie’s fictional Corinth University, a recurrent setting for her novels, is the backdrop of this acclaimed 1974 study of the upending of a faculty marriage in a town closely resembling Ithaca—and, unsurprisingly, many on the real-life campus speculated wildly about whom the characters may have been modeled on. A TV version, starring Elizabeth Ashley and Richard Crenna, aired in 1977. Lurie taught English on the Hill for nearly three decades before retiring as a professor emerita in 1998. Her other novels include Foreign Affairs, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1985 (and also became a TV movie, starring Joanne Woodward and Brian Dennehy).

Cosmos Carl Sagan

While the late astronomer won the Pulitzer for The Dragons of Eden, it’s for Cosmos—both the phenomenally popular PBS TV series and its accompanying book, published in 1980—that he’s best remembered. “The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be,” Sagan wrote. “Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us—there is a tingling in the spine, a catch in the voice, a faint sensation, as if a distant memory, of falling from a height. We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.” The book, which won a Hugo Award for nonfiction, was re-released in 2013 with a forward by his widow, Ann Druyan, and an essay by astronomer Neil deGrasse Tyson, host of a rebooted “Cosmos” series.

The Elements of Style William Strunk Jr., PhD 1896 & E. B. White ’21

Known on campus as “the little book,” Strunk’s quintessential guide to the mother tongue fell into disuse after the legendary English professor’s retirement in 1937. It got a second life two decades later, when White lauded it in the New Yorker as “a forty-three-page summation of the case for cleanliness, accuracy, and brevity in the use of English.” With some reworking—White’s original manuscript is housed in Kroch Library—it became a bestseller after its publication in 1959. (As one bookstore clerk wrote to White: “It’s propped up on the front table with all the other ‘hot’ paperbacks—between the Rand McNally Road Atlas and The Joy of Sex. And it’s selling faster than either one of them.”) Generations of students have been schooled in its precepts, including “Omit needless words”; “Use definite, specific, concrete language”; and “Use the active voice.”