In an excerpt from their new book about the GI Bill, the Cornell historians describe how the landmark postwar legislation not only aided veterans and benefited society at large, but transformed campuses. “Americans began to perceive undergraduate and graduate degrees as gateways to the professions,” they write, “the new route to the American Dream.”

In an excerpt from their new book about the GI Bill, the Cornell historians describe how the landmark postwar legislation not only aided veterans and benefited society at large, but transformed campuses. “Americans began to perceive undergraduate and graduate degrees as gateways to the professions,” they write, “the new route to the American Dream.”

In an excerpt from their new book, two Cornell historians describe how the GI Bill transformed American campuses

By Glenn Altschuler & Stuart Blumin

By the spring of 1946, Time reported, it was "standing room only" in many of the 2,268 universities, colleges, and junior colleges approved by the Veterans Administration as eligible for reimbursement under Title II of the GI Bill. Three hundred thousand World War II veterans had enrolled, more than three times the number of matriculants in the entire year of 1945. Millions more were on the way. In 1945, 88,000 of 1.6 million students were GIs. By 1947, 2.3 million men and women had enrolled in colleges and universities, 1.15 million of them veterans of World War II. The dilemma of administrators in higher education, wrote Milton MacKaye in the Saturday Evening Post, was akin to that of the family "who inherited a herd of elephants: where to put them. . . . The bitter tea of the educators is this: the dream of opportunity is at hand, and the colleges do not have the facilities, the housing, the instructors or classrooms to handle it."

With a big assist from federal and state governments, institutions of higher education struggled to meet the challenge. The impact on American society and culture cannot be measured with precision, but by all accounts the investment in human capital made through the GI Bill yielded enormous dividends. Hundreds of thousands of Americans who otherwise would not have returned to school completed undergraduate and graduate degrees. Along with the GIs who would have resumed their education without the legislation, they added 450,000 engineers, 180,000 doctors, dentists, and nurses, 360,000 teachers, 150,000 scientists, 243,000 accountants, 107,000 lawyers, and 36,000 clergymen to the ranks of the nation's professionals. Although the GI Bill was, at best, a mixed blessing for women and African Americans—its benefits fell disproportionately on white males—it clearly sustained postwar prosperity, fueled a revolution in rising expectations, and accelerated the shift to the postindustrial information age.

Less noted was the impact of Title II on institutions of higher education. The massive influx of veterans resulted in changes— some of them permanent and profound—in the physical plants, admissions procedures, guidance and testing services, curriculum, pedagogy, and relationship to the government of American colleges and universities. Most important, the GIs' academic achievements enhanced the prestige, practical value, and visibility of a college diploma. Harold Stoke, president of the University of New Hampshire, was perhaps too sanguine in proclaiming that the GI Bill had "unwittingly imposed compulsory education on the nation." The legislation, however, did help forge a consensus that the number of college-caliber candidates, drawn from all socioeconomic and ethnic groups, was far larger than previously thought. Americans began to perceive undergraduate and graduate degrees as gateways to the professions, the new route to the American Dream.

In 1946, Title II of the GI Bill remained an experiment with an uncertain outcome. Considering it "their bounded duty to open the doors of opportunity to the multitudes"—and not unmindful of the tuition pouring into bursars' offices—colleges and universities scrambled to accommodate as many students as possible. Enrollments on many campuses exploded. At Purdue University, degree matriculants jumped from 5,628 in 1945 to 11,462 in 1946. The enrollment at Syracuse University in 1945 was 4,391; a year later it had swelled to 15,228.

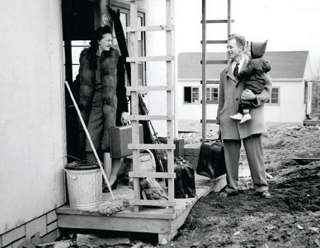

Housing the veterans was the most pressing problem. Of 100 colleges polled by the American Council on Education in 1945 (before eligibility under Title II was liberalized), eighty-seven reported shortages. These institutions alone needed 47,300 single rooms and an additional 22,120 apartments (to accommodate the families of married veterans). At first, the Veterans Administration refused to help with housing because it segregated veterans from civilian students and put them "in a special category." Congress raced to the rescue. In a series of amendments to the Lanham Act of 1940, which authorized the federal government to construct public housing to facilitate the nation's defense, the House and the Senate authorized the National Housing Agency to rent housing to veterans, construct temporary units for them, move facilities to sites approved by colleges and universities, and reimburse institutions that had already incurred expenses in doing so. Congress appropriated almost $450 million for these initiatives. When the funds ran out in August 1946, 101,462 accommodations had been transferred to institutions of higher education.

In addition to the East Vetsburg and Tower Road complexes, Cornell leased the Glen Springs Hotel in Watkins Glen, a once luxurious facility with a country club.An additional 100,000 units came from government facilities located near college campuses. Just about anything with four walls, including Quonset huts and mess tents, sufficed. Quarters once utilized by bachelor officers at Kirtland Field housed students at the University of New Mexico; barracks at Camp Kilmer and a prefabricated steel factory, about to be delivered to the Soviet Union, were turned over to Rutgers University; Hiram College in Ohio gained access to apartments at the Ravenna Ordnance Plant; Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute leased LSTs (landing ship tanks), floating in the Hudson River, to accommodate 600 veterans; and the government converted thirty-nine prisoner-of-war barracks from Weingarten, Missouri, into 117 housing units for veterans enrolled at Notre Dame. At peak enrollment, historian Keith Olson has estimated, perhaps 300,000 student veterans lived in facilities acquired under the Lanham Act amendments.

Colleges and universities also used their own resources to add housing stock. In addition to the East Vetsburg and Tower Road complexes on its Ithaca campus, for example, Cornell leased the Glen Springs Hotel in Watkins Glen, a once luxurious facility with a country club, health resort, and golf course that had been unoccupied for four years. Cornell converted the hotel into apartments for 135 married veterans, an infirmary, a sun porch, and a recreation lounge for dancing. Meals were served in a cafeteria set up in the main dining room. Although New York State provided assistance for the project, the University's contribution included $50,000 for furnishings and equipment and about $26,000 a year to bus the students to Ithaca, a round trip of more than fifty miles.

In addition to housing, colleges and universities provided more classrooms, laboratories, libraries, and offices for faculty and administrators. Convinced that the battle of the (enrollment) bulge would last no more than four years, Veterans Administration director Frank Hines insisted that permanent additions to the physical plant constituted "expansion to destruction." In August 1946, with the Veterans' Educational Facilities Program (VEFP), Congress amended the Lanham Act yet again to permit and pay for the disassembly, transportation, and reassembly of surplus military buildings on the campus of any Title II institution facing a temporary shortage of floor space. At a cost of about $80 million the government moved 5,920 structures, including ordnance depots, military barracks, and Quonset huts, to more than 700 colleges, where they became makeshift classrooms and faculty offices. Two other provisions of the VEFP permitted educational institutions to acquire without cost or purchase in advance of public sale surplus government property, including furniture, textbooks, cars, lockers, electronics equipment, air conditioners, chemicals, and medicine. By the end of 1948, assets valued at almost $125 million had been transferred.

In addition to housing, colleges and universities provided more classrooms, laboratories, libraries, and offices for faculty and administrators. Convinced that the battle of the (enrollment) bulge would last no more than four years, Veterans Administration director Frank Hines insisted that permanent additions to the physical plant constituted "expansion to destruction." In August 1946, with the Veterans' Educational Facilities Program (VEFP), Congress amended the Lanham Act yet again to permit and pay for the disassembly, transportation, and reassembly of surplus military buildings on the campus of any Title II institution facing a temporary shortage of floor space. At a cost of about $80 million the government moved 5,920 structures, including ordnance depots, military barracks, and Quonset huts, to more than 700 colleges, where they became makeshift classrooms and faculty offices. Two other provisions of the VEFP permitted educational institutions to acquire without cost or purchase in advance of public sale surplus government property, including furniture, textbooks, cars, lockers, electronics equipment, air conditioners, chemicals, and medicine. By the end of 1948, assets valued at almost $125 million had been transferred.