Bishop's secret mystery gets a second chapter

BISHOP'S SECRET MYSTERY GETS A SECOND CHAPTER

mORRIS BISHOP SPENT HIS LIFE AT CORNELL. He earned an undergraduate degree in 1913 and a PhD in 1926, taught Romance literature for half a century, penned the seminal A History of Cornell. Off the Hill, he's known for his definitive history of the Middle Ages, his New York Times book reviews, and the light verse he published in the New Yorker.

mORRIS BISHOP SPENT HIS LIFE AT CORNELL. He earned an undergraduate degree in 1913 and a PhD in 1926, taught Romance literature for half a century, penned the seminal A History of Cornell. Off the Hill, he's known for his definitive history of the Middle Ages, his New York Times book reviews, and the light verse he published in the New Yorker.

Few people remember the woman he killed in Uris Library.

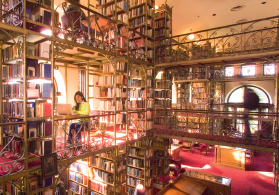

Her name was Lucie Coindreau, a French professor found in an ornate reading room with her neck broken, her head surrounded by an "ever-widening stain" of blood.

Though her death was initially labeled an accident, her murderer was ultimately brought to justice by librarian Gilda Gorham, a spunky young woman and a stick-ler for library rules.

Gilda is the protagonist of The Widening Stain, Bishop's only foray into mystery fiction. Published in 1942 by Knopf under the pseudonym W. Bolingbroke Johnson, the comic novel was reissued in August by Rue Morgue Press; according to the publisher's president, Tom Schantz, sales of the initial print run of 2,300 have been surprisingly brisk. "It's an enjoyable book, and it's from the period when academics were in love with detective fiction," he says. "For 1942, the heroine is very much a forerunner of the modern woman amateur detective."

Rue Morgue acquired the copyright to The Widening Stain from Bishop's daughter, Alison Jolly '58, a primatologist in Sussex, England, who does frequent fieldwork in Madagascar. ("Our chief problem," Schantz says of getting permission for the reprint, "was that she was always off looking at lemurs.") Jolly stresses that her father went to great pains to set the story at a fictitious university and avoid basing his characters on real people—but after it was published he was contacted by academics throughout the Ivy League who were sure they recognized someone. The exterior of the library where Lucie dies is based on a building at Yale, she says, but the interior clearly comprises the A. D. White Library as well as the Uris crypt, formerly home to Cornell's rare book collection. "On the way down to the crypt," Jolly recalls in an e-mail, "Pop would show me that bound volumes of the New York Times might well be fatal if they fell on you."

The novel is filled with Bishop's signature limericks; the author himself jotted one in a copy housed in Olin Library, obliquely acknowledging his identity. "A cabin in northern Wisconsin / Is what I would be for the nonce in, / To be rid of the pain / of The Widening Stain / and W. Bolingbroke Johnson." Although Bishop long denied authorship, says University Archivist Emeritus Gould Colman '51, PhD '62, he more or less did it with a twinkle in his eye, and "everybody knew who wrote it." As Bishop said in a note to a friend in June 1941: "I am writing a mystery story. The mystery itself would not deceive an intelligent chimpanzee, but I think I can make it more obscure on second writing. The background may carry it. Most of it is laid in our University Library, a kind of Notre-Dame de Paris. I have written half the book in three weeks, so there will be no great loss if no one wants to publish it, and in the meantime it serves as a most admirable retreat. Come to think of it, 'The Corpse in the Ivory Tower' wouldn't be a bad title."