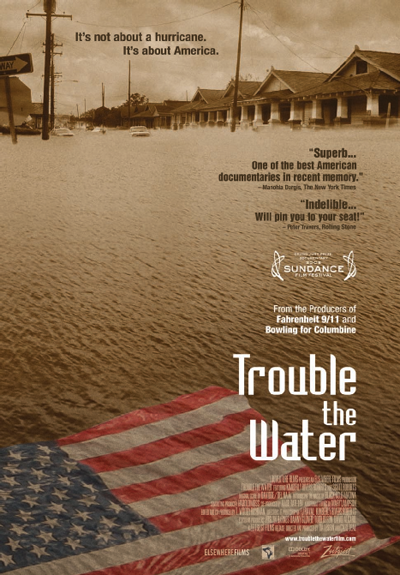

Tia Lessin ’86, BA ’88, learned the art of activist filmmaking from the master: documentarian Michael Moore. Last year, she got an Oscar nomination for Trouble the Water, a documentary about the struggles of New Orleans’s poorest residents during and after Hurricane Katrina. For Lessin—whose in-your-face style got her banned from Disney World—"storytelling is all about conflict."

Tia Lessin ’86, BA ’88, learned the art of activist filmmaking from the master: documentarian Michael Moore. Last year, she got an Oscar nomination for Trouble the Water, a documentary about the struggles of New Orleans’s poorest residents during and after Hurricane Katrina. For Lessin—whose in-your-face style got her banned from Disney World—"storytelling is all about conflict."

Filmmaker Tia Lessin's efforts to change the world earned her an Oscar nomination—and a lifetime ban from Disney World

By Brad Herzog

February 2009. Oscar night. The red carpet. A parade of stars and filmmakers weaves through a gauntlet of flash-bulbs, microphones, and giant replicas of gold statuettes. Television hosts, breathlessly informing viewers that Kate Winslet is wearing "a steel gray Yves St. Laurent asymmetrical gown with a black silk overlay," are buttonholing celebrities as they make their way into L.A.'s Kodak Theatre. Sophia Loren gushes about the "absolutely wonderful" night. Miley Cyrus plugs her new movie. It is the climax of Hollywood's self-congratulatory season—the epicenter of style, if not substance.

But here comes Tia Lessin '86, BA '88. Her ninety-six-minute film, Trouble the Water—the story of two residents of New Orleans's Lower Ninth Ward and their travails following the devastation of Hurricane Katrina—has been nominated for Best Documentary. The interviewers ask a few cursory questions and seem eager to move on. After all, Anthony Hopkins is on his way, as is the cast of Slumdog Millionaire. However, Lessin has something on her mind. "People are still struggling all along the Gulf Coast," she says, practically grabbing the microphone. "We're here to represent them and to make it clear that the region and so many regions around the country still need help."

Now that's focus.

Now that's focus.

When Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in August 2005, Lessin was as stunned and outraged by the images on television as the rest of the nation. At first, she figured the media was all over the story. What could she possibly add to the conversation? But then she and Carl Deal—her longtime producing, directing, and life partner—noticed that the press coverage began to turn. "They started to sensationalize all the looting and that was sort of adding insult to injury," she says. "I felt they were characterizing the people left behind as criminals. So that's when Carl and I thought, OK, we can do something here."

Usually, the process would have been gradual and organized: think of an idea, write a treatment, do some preliminary scouting and interviews, perhaps cobble together grants or get a commission from a broadcaster. But there wasn't time. "We didn't have a treatment," says Lessin. "We just had an impulse."

Deal had spent years working in international news gathering, so he was used to the spontaneous pursuit of a story. And Lessin's apprenticeship under documentarian Michael Moore had honed her ability to find a compelling hook. As an Emmy-nominated producer for both of his short-lived television shows, "TV Nation" and "The Awful Truth," she often found profundity in the absurd. Lessin staged a mock funeral outside health insurer Humana's corporate headquarters after a policyholder was denied funds for a potentially life-saving pancreas transplant. She conceived the idea of the "Sodomobile," a pink van loaded with gay men and women trying to break every sodomy law in the country. With a character named Crackers the Corporate Crime Fighting Chicken, she traveled to Disney World to expose allegedly unfair labor practices. She was eventually arrested for filming without a permit—and banned for life from the Happiest Place on Earth.

So Lessin was accustomed to following the whiff of a story, and she found a unique angle in the tale of thousands of Louisiana National Guard soldiers returning home from Iraq, decommissioned so they could help their displaced families. She was intrigued by the fact that the men and women charged with protecting American citizens had been half a world away when their communities needed them most. Lessin and Deal didn't know if there was a movie in there, but it was a starting point.

The pair assembled a crew, borrowed some equipment, cashed in their frequent flyer miles, headed from their Brooklyn home to the Joint Readiness Training Center in Louisiana, and started asking questions. Why were most of the state's high-water vehicles left in Baghdad? What use would a high-water vehicle be in the desert anyway? It was about that time that a National Guard PR representative cut off access to the troops, explaining bluntly, "Fahrenheit 9/11 screwed it up for all you guys."

Of course, the rep had no idea that Lessin and Deal had worked on that Michael Moore film, which won the Palm d'Or as the best film at the Cannes Film Festival and became the highest grossing documentary in history. The year they spent producing the film, says Lessin, was "one of the most amazing experiences. We were trying to stop a war. We were trying to unseat a president. We had high ambitions, not only to make a beautiful film, but to make change."

But rule number one in documentary filmmaking is this: respond to what you encounter in the here and now. You can research, strategize, make phone calls, prepare as much as possible, but you have to be in the moment and react accordingly. "The audience isn't going to respond to anything unless you as a filmmaker and your camera are responding to it," says the forty-five-year-old Lessin. "So we go by instinct."

Those instincts led them to a Red Cross shelter next to the National Guard armory, where they were approached by a young African American couple who had made their way out of New Orleans a week earlier. Scott and Kimberly Rivers Roberts, self-described street hustlers, had been barely scratching out an existence in the Lower Ninth Ward, primarily by dealing drugs. Kim, an aspiring rapper whose mother had died of HIV, had bought a $20 camcorder just before the storm. "What I got, I've been saving it, 'cause I don't want to give it to nobody local," she told the filmmakers. "This needs to be worldwide. 'Cause all the footage I've seen on TV, nobody got what I got. I got right there in the hurricane."

It was certainly amateur footage: jumpy, raw . . . and riveting. It began with the daily grind of impoverished New Orleans and the community's collective shrug at the realization that most of its residents, with no means of evacuating, would have to face the coming onslaught. Then it showed the winds whipping, the streets flooding, Kim and Scott rescuing neighbors and taking refuge in an attic as the waters rose. It was the hurricane seen from the inside, looking out. "The more time we spent with them, we realized, wow, they have a story to tell," says Lessin, "and the story didn't seem to start with Katrina."

Still, the filmmakers had a more sweeping movie in mind. They shot 160 hours of material, planning to dovetail various stories and paint an epic picture of a hurricane's devastation. But then came the news that Spike Lee was making a four-part series on Katrina, backed by millions of dollars from HBO. "We realized we couldn't make that film," Lessin recalls, "and that ours was going to have to be more focused and intimate."

The story of Kim and Scott Roberts resonated because it touched on so many issues that Katrina uncovered, including the abandonment not only of the city's poorest, but also the incarcerated (Kim's brother) and the hospitalized (Kim's grandmother, who was among hundreds who died). Lessin and Deal filmed them on and off for two years—as they made their way out of the city, to her uncle's trailer in central Louisiana, then to the home of relatives in Memphis, and finally back to their community with a newfound sense of purpose.

The filmmakers spent some nine months in the editing room, distilling Kim's raw footage to about fifteen minutes, sifting through archival material, trying to determine if their story could sustain an audience for an hour and a half. The final product unfolds in raw vignettes. It portrays the residents of the Lower Ninth Ward—inevitably pigeonholed by the news media as either helpless victims or criminals—as multi-dimensional and resourceful. "They were complicated people who were also pretty resilient in taking charge of their lives," says Lessin, "and they became their own first responders because there was no one there to help." As a reviewer for Salon.com put it, the film tells a story "in which Hurricane Katrina is both tragedy and opportunity."