When Corey Earle ’07 was accepted early decision, his parents gave him a signed, first-edition copy of Morris Bishop’s A History of Cornell. The son and grandson of alumni who spent their careers on the faculty, Earle read the book the summer before he matriculated—the thirteenth member of his family to attend. In short, when it comes to Cornell lore, he may well have been the most prepared freshman ever.

Corey Earle ’07

Earle kept up the Cornell history habit as a CALS student majoring in communication—the department where his father, Brian Earle ’68, MPS ’71, taught for four decades and still maintains a presence in semi-retirement. As an undergrad, his trove of some 200 Cornell-related volumes won the University Library’s annual book collecting contest (it has since grown to more than 300), and the Daily Sun tapped him for a biweekly column on University history. When the library digitized the Cornell Alumni News back to its inception in 1899, he read every issue. “I was amazed at the crucial role that Cornell played in the development of higher education in the U.S.,” Earle says. “I don’t think a lot of students, or even faculty and staff, are aware of that. So I made it my crusade to raise awareness of Cornell’s history and try to spread the Cornell gospel.”

Three guesses where Earle—following in the footsteps of his brother, Evan ’02—went to work after graduation. He first served as a reference specialist in Kroch Library before moving over to Alumni Affairs and Development—where, as associate director of student programs, his duties include running the senior class campaign. “We’re training students to be good alumni,” he says. “We want them to feel like they’re part of the Cornell community, to create a culture of philanthropy and gratitude.”

Three guesses where Earle—following in the footsteps of his brother, Evan ’02—went to work after graduation. He first served as a reference specialist in Kroch Library before moving over to Alumni Affairs and Development—where, as associate director of student programs, his duties include running the senior class campaign. “We’re training students to be good alumni,” he says. “We want them to feel like they’re part of the Cornell community, to create a culture of philanthropy and gratitude.”

But he has also carved out a niche as a one-man repository of University history, building Big Red spirit by giving talks on campus and beyond. His traveling slideshow covers not only the familiar genesis tale (how the lowly born, self-taught Ezra Cornell made a fortune in the telegraph business and teamed up with cultured blue-blood Andrew Dickson White to found the school on the Hill) but many assorted gems of Cornelliana—from the Brain Collection to the live bear mascot to the infamous pumpkin atop McGraw Tower. In addition to a general round-up of Cornell facts both well known and obscure, he has created trivia quizzes, talks geared to special occasions such as Halloween, and presentations using University history to spark discussion about topics like ethics. “The best part,” says Earle, “is that I learn so much each time I do it, especially when speaking to alumni. They lived through history.”

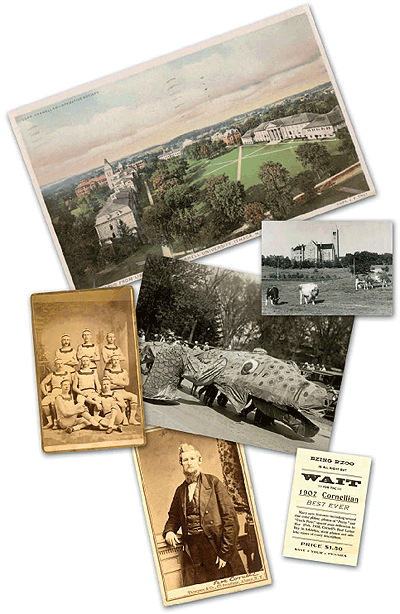

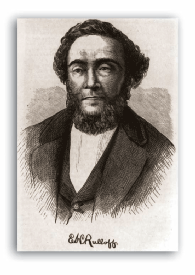

Big Red memories: As Earle tells his audiences, Cornell is often called “the first American university”—combining the practicality of Midwestern schools with the classicism of the Ivy League. Clockwise from top: A 1913 postcard of the Arts Quad; cows on Libe Slope in 1891; a 1920s Dragon Day; an ad for the 1907 Cornellian; a portrait of Ezra Cornell from the 1860s; and the 1876 men’s varsity crew.

BRAIN POWER

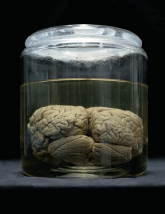

“I love the Brain Collection,” Earle says. “It’s a quintessential part of Cornelliana.” Still on display in Uris Hall, the collection was founded in 1889 by zoology professor Burt Green Wilder, a member of the original faculty. “He kept a menagerie of animals, including a bear, in the basement of McGraw Hall,” Earle says. “One story is that when they painted the ceiling of Sage Chapel, he was so disgusted at the musculature of the angels—that it was anatomically incorrect, because it would make it physically impossible for them to have wings—that he refused to enter.” Wilder donated his own brain to the collection, which at its peak comprised some 1,600 samples. “Goldwin Smith donated his brain,” Earle says, “but it got stuck in Canadian customs and rotted at the border.”

“I love the Brain Collection,” Earle says. “It’s a quintessential part of Cornelliana.” Still on display in Uris Hall, the collection was founded in 1889 by zoology professor Burt Green Wilder, a member of the original faculty. “He kept a menagerie of animals, including a bear, in the basement of McGraw Hall,” Earle says. “One story is that when they painted the ceiling of Sage Chapel, he was so disgusted at the musculature of the angels—that it was anatomically incorrect, because it would make it physically impossible for them to have wings—that he refused to enter.” Wilder donated his own brain to the collection, which at its peak comprised some 1,600 samples. “Goldwin Smith donated his brain,” Earle says, “but it got stuck in Canadian customs and rotted at the border.”

STRAIGHT SCOOP

As an undergrad, Willard Straight 1901 felt that the Architecture college didn’t have enough spirit—so he founded Dragon Day. He went on to a career as a diplomat; when he died of pneumonia after World War I, he left his estate to the University, “to make Cornell a more human place.” Willard Straight Hall became one of the nation’s first student unions; when it was built in 1925, Earle notes, “it was unusual to have a building with no academic purpose.”

WHITHER ‘BIG RED’?

The name “Big Red” traces its roots to a song. In 1905, the football team had a contest to write a football song, Earle says, “because they were jealous of the crew team.” The winner was celebrated humorist Rym Berry 1904 with a ditty called “The Big Red Team.”

BEANIE BABIES

“Back in the day, all freshmen, male and female, were required to wear the freshman beanie,” Earle says. “If you were caught on campus without it, you’d be in trouble.” A “sophomore vigilance committee” was in charge of enforcing the rules, which also banned smoking, walking on the grass, or entering certain bars, such as Zinck’s. “A lot of these rules vanished after World War II, when hundreds of veterans came to campus,” Earle points out. “You had freshmen who were five years older than the seniors, so having a sophomore tell a grizzled veteran of World War II that he had to keep his cap on didn’t go over so well.”

BEAR FACTS

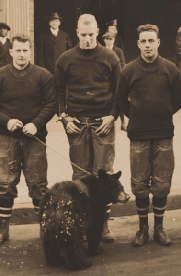

In 1915, some alumni decided that Cornell needed a mascot—so they donated a bear cub, who was dubbed Touch-down. “The manager of the football team suddenly became bear caretaker,” Earle says. “They’d take the bear with them to away games. They’d bring it on the train and it would stay in hotels with them. There are a lot of good stories of the bear getting loose in hotel lobbies or at bars and terrorizing people. None of the bears lasted longer than a season, because by the end it was a little larger than it started out.” Earle notes that Touchdown’s inaugural year corresponds with Cornell’s first national football championship—and that the last time the Big Red had a live mascot (Touchdown IV, in 1939), it won its last national title. “So if you ask me,” Earle says, “it’s not a new coach that we need, it’s a bear cub.”

In 1915, some alumni decided that Cornell needed a mascot—so they donated a bear cub, who was dubbed Touch-down. “The manager of the football team suddenly became bear caretaker,” Earle says. “They’d take the bear with them to away games. They’d bring it on the train and it would stay in hotels with them. There are a lot of good stories of the bear getting loose in hotel lobbies or at bars and terrorizing people. None of the bears lasted longer than a season, because by the end it was a little larger than it started out.” Earle notes that Touchdown’s inaugural year corresponds with Cornell’s first national football championship—and that the last time the Big Red had a live mascot (Touchdown IV, in 1939), it won its last national title. “So if you ask me,” Earle says, “it’s not a new coach that we need, it’s a bear cub.”

A DEADLY PRANK

Traditionally, the sophomores would try to sabotage the annual freshman banquet, generally by kidnapping the class president to make him miss the party. But in 1894, class rivalry hit a new high—or, rather, low—when some sophomores pumped chlorine gas into the banquet room of a downtown hotel via holes drilled in the floor. “Whether they had failed chemistry is not known,” Earle says. Freshmen started collapsing, rushing out of the building, and pulling each other to safety. In the end, the single casualty was the cook, whose death prompted a criminal investigation and strained town-gown relations. “No one in the sophomore class would come forward,” Earle says. “The ingredients were traced back to two class members; they refused to testify and were jailed for contempt, but successfully appealed on Fifth Amendment grounds.” The judgment became part of case law on “pleading the Fifth.”

LIFE BEFORE LYNAH

Once upon a time, the hockey team played on Beebe Lake—which probably sounds more romantic than it actually was. “This meant that away teams could spend a whole day on a train, and when they got here the ice would have melted and the game would have to be called off,” Earle says. “So it wasn’t the most convenient setup. Some years the season would be twelve games long, some years two, depending on the weather.” The Big Red stopped using the lake in the Forties—so, as unthinkable as it may be today, Cornell went a decade without a hockey program until Lynah Rink opened in 1957.

Once upon a time, the hockey team played on Beebe Lake—which probably sounds more romantic than it actually was. “This meant that away teams could spend a whole day on a train, and when they got here the ice would have melted and the game would have to be called off,” Earle says. “So it wasn’t the most convenient setup. Some years the season would be twelve games long, some years two, depending on the weather.” The Big Red stopped using the lake in the Forties—so, as unthinkable as it may be today, Cornell went a decade without a hockey program until Lynah Rink opened in 1957.

SOUP TO NUTS

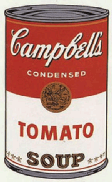

If Campbell’s Soup cans inspire Big Red spirit, it’s because the design is actually based on Cornell’s signature colors. As Earle tells it, a Campbell’s executive went to the Cornell-Penn game on Thanksgiving 1898— and “he was so impressed with the colors, he said, ‘We should make our cans red and white.’ ” Cornell lost that day, but its colors have graced Campbell’s labels for more than a century.

If Campbell’s Soup cans inspire Big Red spirit, it’s because the design is actually based on Cornell’s signature colors. As Earle tells it, a Campbell’s executive went to the Cornell-Penn game on Thanksgiving 1898— and “he was so impressed with the colors, he said, ‘We should make our cans red and white.’ ” Cornell lost that day, but its colors have graced Campbell’s labels for more than a century.

THE ‘EZRA LETTER’

When Sage Hall was built in 1873, Ezra wrote a letter that was sealed into the cornerstone; should the University fail, he told his contemporaries, the letter would explain why. Since Sage was built as a women’s residence, it was assumed that the letter addressed issues of coeducation. But when the cornerstone was opened during Sage’s gut renovation in the Nineties, the long-awaited missive proved to be about something else: religion. “Ezra was concerned that the non-sectarian nature of the University would be its downfall,” Earle says, “that pressure from religious critics might prevent the ‘any person’ ideal from holding true.”

When Sage Hall was built in 1873, Ezra wrote a letter that was sealed into the cornerstone; should the University fail, he told his contemporaries, the letter would explain why. Since Sage was built as a women’s residence, it was assumed that the letter addressed issues of coeducation. But when the cornerstone was opened during Sage’s gut renovation in the Nineties, the long-awaited missive proved to be about something else: religion. “Ezra was concerned that the non-sectarian nature of the University would be its downfall,” Earle says, “that pressure from religious critics might prevent the ‘any person’ ideal from holding true.”

THAT’S OUR MOTTO

Cornell is the only Ivy League school with an English motto: I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study. In his talks, Earle deconstructs how the motto offered inclusion on five fronts—noting that, “in 1865, these were radical concepts.”

Any gender—”It didn’t say ‘any man’; it said ‘any person,'” Earle points out. “This was the close of the Civil War, and there were no major coeducational institutions in the U.S. Cornell was the first to admit women alongside men.” In the Twenties, when the League of Women Voters published a list of the twelve greatest women in the country, three were Cornellians: naturalist Anna Botsford Com-stock, Cornell’s first female professor; home economics pioneer and Cornell dean Martha Van Rensselaer; and Martha Carey Thomas 1877, second president of Bryn Mawr College.

Any ethnicity—From the outset, the University was open to people of any race. Alpha Phi Alpha, the first African American, intercollegiate Greek letter fraternity in the U.S., was founded at Cornell in 1906.

Any nationality—At a time when few universities had international students, Cornell’s first class included people from Russia and Brazil.

Any religion—”The other institutions of the time were pretty much of one faith or sect; it would be a Presbyterian school or a Methodist school,” Earle notes. In his talks, he displays a page from an early yearbook listing class statistics that included religious affiliation, with responses ranging “from Hebrew to heathen.” “At any other school you’d get kicked out if you said you were a heathen, but at Cornell that was just fine,” Earle says. “Cornell got a lot of negative press for this—we were called ‘the godless institution.’ As a joke, a group of students once formed the Infidels Association.”

Any socioeconomic class—As a self-taught man raised in modest circumstances, Ezra wanted his university to welcome people from all walks of life. Says Earle: “Cornell had an early version of the work-study system, where the students built McGraw Hall to pay their tuition.”

STUCK IN THE MUD (RUSH)

Class rivalry used to be much more intense than it is now, Earle says. Among the quaint traditions of yesteryear: the Mud Rush, “which was basically the freshman and sophomore classes beating the crap out of each other.” Another popular tradition, known as the cane rush, involved trying to steal a stick that served as the class symbol. “It would turn into an all-out brawl—people would break arms and legs, clothes would be torn off,” Earle says. “Today, I think Risk Management would have a problem with it.”

Class rivalry used to be much more intense than it is now, Earle says. Among the quaint traditions of yesteryear: the Mud Rush, “which was basically the freshman and sophomore classes beating the crap out of each other.” Another popular tradition, known as the cane rush, involved trying to steal a stick that served as the class symbol. “It would turn into an all-out brawl—people would break arms and legs, clothes would be torn off,” Earle says. “Today, I think Risk Management would have a problem with it.”

STAR POWER

Actors who have attended Cornell include the late Christopher Reeve ’74 of Super-man fame; “L.A. Law” and “West Wing” star Jimmy Smits, MFA ’82; Ellen Albertini Dow ’35, MA ’38, who has played a spunky senior citizen in films like The Wedding Singer and Wedding Crashers; and Jane Lynch, MFA ’84, currently cast as the abrasive cheerleading coach on “Glee.” Peter Ostrum, who was Charlie Bucket in the original 1971 Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, earned a DVM from Cornell in 1984; Frank Morgan 1909, immortalized in the title role of The Wizard of Oz, dropped out after freshman year. Famous fictional Cornellians include Charles Foster Kane of Citizen Kane, unrelenting Big Red booster Andy Bernard of “The Office,” and animated sidekick Sideshow Mel of “The Simpsons.” Cornell has also figured in a number of recent films, including Up in the Air (as the alma mater of George Clooney’s ambitious protégé) and The Informant, about the escapades of ADM whistleblower (and multi-million-dollar embezzler) Mark Whitacre, PhD ’83. At the end of the film, Whitacre is seen leaving federal prison wearing a Cornell sweatshirt.

Actors who have attended Cornell include the late Christopher Reeve ’74 of Super-man fame; “L.A. Law” and “West Wing” star Jimmy Smits, MFA ’82; Ellen Albertini Dow ’35, MA ’38, who has played a spunky senior citizen in films like The Wedding Singer and Wedding Crashers; and Jane Lynch, MFA ’84, currently cast as the abrasive cheerleading coach on “Glee.” Peter Ostrum, who was Charlie Bucket in the original 1971 Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, earned a DVM from Cornell in 1984; Frank Morgan 1909, immortalized in the title role of The Wizard of Oz, dropped out after freshman year. Famous fictional Cornellians include Charles Foster Kane of Citizen Kane, unrelenting Big Red booster Andy Bernard of “The Office,” and animated sidekick Sideshow Mel of “The Simpsons.” Cornell has also figured in a number of recent films, including Up in the Air (as the alma mater of George Clooney’s ambitious protégé) and The Informant, about the escapades of ADM whistleblower (and multi-million-dollar embezzler) Mark Whitacre, PhD ’83. At the end of the film, Whitacre is seen leaving federal prison wearing a Cornell sweatshirt.

OUT OF OUR GOURD

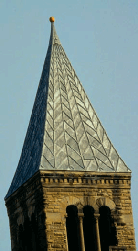

When Earle gives presentations to students, the question he’s asked most often is, “What’s the story with the clocktower pumpkin?” So his lecture includes a detailed account of the day in late October 1997 when the campus woke to find a gourd mysteriously speared atop McGraw Tower. The story immediately caught on with national media; as Earle jokes, “The New York Times basically had a beat writer assigned to it.”

When Earle gives presentations to students, the question he’s asked most often is, “What’s the story with the clocktower pumpkin?” So his lecture includes a detailed account of the day in late October 1997 when the campus woke to find a gourd mysteriously speared atop McGraw Tower. The story immediately caught on with national media; as Earle jokes, “The New York Times basically had a beat writer assigned to it.”

The University cordoned off the grass around the tower with police tape, lest the vegetable fall and kill somebody, and set up a “Pumpkin Cam” with live video streaming on the Web. East Hill was agog with pumpkin mania. Engineers tried to design a device to go up and take samples; the Glee Club sang a pumpkin-themed parody of the Alma Mater on the national news; when the pumpkin failed to rot with the advent of spring, plant science students debated whether it was real.

Ultimately, the administration decided to play it safe and take it down, bringing in a crane and planning a gala ceremony—but during a preliminary run, a gust of wind knocked the crane into the spire and the pumpkin fell off. Ultimately, it was determined to be a genuine, hollowed-out gourd that had been freeze-dried by the Ithaca winter.

So how did it get up there? Years later, a plausible story emerged: skilled rock climbers had attended a chimes concert and hidden in the tower until everyone left, then put tape over a door lock on their way out. They retrieved their equipment and returned to the tower, where they took the stairs to the top, cut open a locked hatch in the roof, and scrambled up to deposit the pumpkin by cover of night. “No one ever took responsibility,” Earle says, “but it has been said the local climbing community is very aware of who the perpetrators are.”

CORNELL’S FAVORITE KILLER

“Probably the best spooky story about Cornell is Rulloff,” Earle says. “He’s Ithaca’s most famous criminal.” In the mid-nineteenth century, Edward Rulloff was a schoolteacher in nearby Dryden when his wife and infant vanished; around the same time, a neighbor was asked to help Rulloff carry a large trunk to his carriage. He was assumed to have murdered them in a rage and tossed them in the lake—but since their bodies were never found, he was prosecuted for kidnapping. He escaped from custody after befriending the son of the jailkeeper and continued his life of crime. A sociopath who fancied himself an unsung genius in the field of philology, he was eventually arrested for the murder of a Binghamton shopkeeper. After being convicted in 1870 in what Earle calls “the O. J. Simpson trial of the mid-1800s,” he became the last person publicly hanged in New York State. A jailhouse interview shortly before his death cemented his legend. “He said, ‘You cannot kill an unquiet spirit, and I know that my impending death will not mean the end of Rulloff. In the dead of night, walking along Cayuga Street, you will sense my presence. When you wake to a sudden chill, I will be in the room. And when you find yourself alone at the lake shore, gazing at gray Cayuga, know that I was cut short and your ancestors killed me . . .’ He gave this really spooky statement, and afterward there were sightings of Rulloff’s ghost along Cayuga Lake.” While not strictly a Cornellian, Rulloff lives on as the namesake of a popular Collegetown eatery. His brain, which is on view in Cornell’s collection in Uris Hall, is among the largest on record.

“Probably the best spooky story about Cornell is Rulloff,” Earle says. “He’s Ithaca’s most famous criminal.” In the mid-nineteenth century, Edward Rulloff was a schoolteacher in nearby Dryden when his wife and infant vanished; around the same time, a neighbor was asked to help Rulloff carry a large trunk to his carriage. He was assumed to have murdered them in a rage and tossed them in the lake—but since their bodies were never found, he was prosecuted for kidnapping. He escaped from custody after befriending the son of the jailkeeper and continued his life of crime. A sociopath who fancied himself an unsung genius in the field of philology, he was eventually arrested for the murder of a Binghamton shopkeeper. After being convicted in 1870 in what Earle calls “the O. J. Simpson trial of the mid-1800s,” he became the last person publicly hanged in New York State. A jailhouse interview shortly before his death cemented his legend. “He said, ‘You cannot kill an unquiet spirit, and I know that my impending death will not mean the end of Rulloff. In the dead of night, walking along Cayuga Street, you will sense my presence. When you wake to a sudden chill, I will be in the room. And when you find yourself alone at the lake shore, gazing at gray Cayuga, know that I was cut short and your ancestors killed me . . .’ He gave this really spooky statement, and afterward there were sightings of Rulloff’s ghost along Cayuga Lake.” While not strictly a Cornellian, Rulloff lives on as the namesake of a popular Collegetown eatery. His brain, which is on view in Cornell’s collection in Uris Hall, is among the largest on record.

FAMOUS FALSEHOODS

What are Earle’s favorite Cornell “facts” that prove to be way off base? The main one that audiences often ask him about is the University’s supposedly astronomical suicide rate—which, despite the gorge deaths last spring, is actually in line with that of other schools. Also, Earle says, “There’s a story that says the Dairy Bar ice cream isn’t FDA-approved or legal to sell off campus, because the fat content is too high. That’s actually not true; they just have chosen to keep the operation on a smaller scale since its focus is on education, not making money.” Another bit of dairy-related apocrypha: “It was never a requirement to milk a cow before you graduate—though it is on the list of ‘161 Things to Do,’ so most students do try to get some milking in.”

Yet another common falsehood is that the University’s infamous swim test was initiated by a wealthy alum whose child drowned, inspiring a donation to Cornell—with the stipulation that all students learn to swim. “That isn’t true,” Earle says. “It started in the Nineteen-Teens as a Red Cross program for women. Then, as part of military preparedness, men began taking it. For years, men had to do fifty yards and women had to do a hundred. It wasn’t until the Seventies that they equalized it to seventy-five yards for everybody.”

MOTHER OF INVENTION

Cornell educated the inventors of SuperGlue (Harry Coover, PhD ’44), the Heimlich Maneuver (Harry Heimlich ’41, MD ’43), air conditioning (Willis Carrier 1901), and chicken nuggets (Robert Baker ’43). The latter was a Cornell food science professor who made it his mission to design new uses for poultry. Says Earle: “He was sort of the George Washington Carver of chicken.”

PIGSKIN’S POP

Among the Cornellians who had the most influence on the wider world of sports was Glenn “Pop” Warner 1894, who not only coached the Big Red football team but invented the tackling dummy and pioneered such now-standard practices as putting numbers on uniform jerseys. “He credited himself with more rule changes than anyone else—and that’s because they had to create the rules because of things he was doing,” Earle says. “He had creative strategies like sewing a fake football on everyone’s jersey, so it looked like they all had footballs. They also had to make a rule saying, ‘You can’t hide the football under your jersey,’ because he would instruct his players to do that.”

Among the Cornellians who had the most influence on the wider world of sports was Glenn “Pop” Warner 1894, who not only coached the Big Red football team but invented the tackling dummy and pioneered such now-standard practices as putting numbers on uniform jerseys. “He credited himself with more rule changes than anyone else—and that’s because they had to create the rules because of things he was doing,” Earle says. “He had creative strategies like sewing a fake football on everyone’s jersey, so it looked like they all had footballs. They also had to make a rule saying, ‘You can’t hide the football under your jersey,’ because he would instruct his players to do that.”