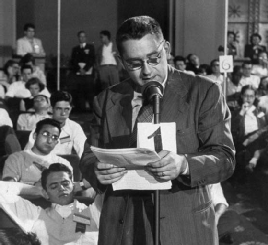

Nobel laureate Robert Fogel '48 rewrites history by the numbers. And those numbers are often controversial.

Nobel laureate Robert Fogel '48 rewrites history by the numbers. And those numbers are often controversial.

Nobel laureate Robert Fogel '48 rewrites history by the numbers. And those numbers are often controversial.

It's two days after Christmas, when not much happens in the work world, let alone in the halls of academia. At the University of Chicago, only a few pedestrians brave the gusty streets, while a security guard keeps tabs on an empty atrium at the Graduate School of Business. But lights gleam in a third-floor corner office. Down the hall from his life-size portrait, economic historian Robert Fogel '48 and several grad students hunch over a conference table, working overtime to finish a grant application due in six weeks at the National Institute on Aging. "We're trying to understand how the process of aging has changed between 1910 and 1980," says Fogel, a professor of American institutions, "to predict the trends in health over the next several decades, and to estimate the cost of health care and Social Security."

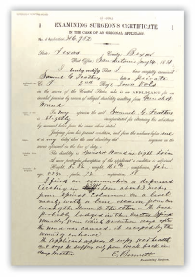

The concept sounds simple enough. But the execution brings new meaning to crunching numbers. For the past twenty years, Fogel has headed a massive study, leading a team of physicians and economic demographers in mining a trove of statistics: the Union Army's military, pension, and medical records for 40,000 white and 6,000 black recruits mustered from 1861 to 1865, with more than 15,000 data points on each soldier from childhood to death. Over the years, they've compared this information to statistics on subsequent generations. Among Fogel's findings: in the past 300 years, humans have become so much more physiologically fit than the previous 7,000 generations that it constitutes what he calls a "technophysio evolution." "I'm interested in measurement— trying to measure things that people speculated about," says Fogel, who directs the Chicago business school's Center for Population Economics. "Can I come up with good measures that tell me what theories to believe and what to discard? It's been a driving interest to know what's true through measurement."

Fogel revolutionized the way economic historians do their work—and pioneered a field called cliometrics—by marrying analysis of hard numbers from the past with sophisticated economic theory. With these methods, he's punctured the conventional wisdom on railroads, slavery, and now health and longevity. He predicts, for example, that children born between 1980 and 1990 have a 50 percent chance of living to 100—fifteen years longer than most experts project. The authors of The 100 Most Notable Cornellians called him an "intellectual agitator," while the London Times included him in its "1,000 Makers of the Twentieth Century." "It was not only his pioneering techniques that made him famous, but the challenging conclusions that he reached," says economics professor emeritus Alfred Kahn, whom Fogel says was his most influential Cornell professor. Perhaps most important, his work has spurred wave after wave of new research in quantitative economic history, one reason Fogel won the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1993, along with Douglass North, a colleague at Washington University in St. Louis.

It was not only his pioneering techniques that made him famous, but the challenging conclusions that he reached,' says economics professor emeritus Alfred Kahn.

Not bad for someone who was once one of the most embattled academics in the country—worthy, one critic said, of a permanent home in "the outermost ring of the scholar's hell, obscurity." That was one assessment of Fogel's audacious 1974 work, Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery, one of the most controversial books about slavery ever published. He and co-author Stanley Engerman showed that the institution was not only profitable, but that slaves worked more efficiently than their Northern counterparts and were not treated as badly as historians had assumed. The book outraged Black Power activists, and the authors were labeled as racists (apparently unaware that Fogel's wife was African American). The debate boiled over into the mass media in America and Europe; publisher Little, Brown and Company called it the twentieth century's most reviewed book. Despite the negative press, Time on the Cross won the 1975 Bancroft Prize, one of history's most prestigious awards, and Engerman says most economic historians now agree with their conclusions. "One of the big games in academics is to ask the right questions," says George Boyer, a professor of labor economics in the ILR school. "You can be a great scholar, but if you're going to ask boring questions, you're going to write boring papers, and no one is going to pay much attention to you. Robert Fogel doesn't ask boring questions."

Fogel entered Columbia for graduate study in economic history in 1956, when most in the field rarely used quantitative data to make their arguments. They debated classic questions, such as what the standard of living of British workers would have been in 1850 had the Industrial Revolution never happened—looking only as far as evidence like infant mortality rates. Lack of computing power stymied more sophisticated analysis. "They came up with answers just by thinking about them—and speculating," Boyer says.

But a movement was stirring to use mathematical models to study history, especially how and why economies and institutions changed; meanwhile, technology was providing computers that could process data much faster and at a much lower cost. The new field would become known as quantitative economic history, or "cliometrics," named for Clio, the Greek muse of history, and metrics, for measurement. For Fogel, cliometrics was the perfect tool to answer his nagging questions about inequity and instability. How did the factory system impact economic and social institutions? How much did new technologies such as railroads and steel mills contribute to economic growth? Given Fogel's interests—and lack of funds for tuition—his advisor suggested that he transfer to Johns Hopkins. It offered not only a scholarship but the chance to study with Simon Kuznets, who would later win the 1971 Nobel Prize in Economics.

It was Kuznets, Fogel has written, who taught him the art of measurement: how to correct incomplete data sets, to figure out how errors in the data had affected one's conclusions, and to use models to evaluate patchy evidence. "There are thousands of different ways that mistakes can be made," he says. "You're always worried. Have you got the right numbers, have you got the right weights, have you added them up in the right way?" Fogel worked for three years to turn his dissertation, on how much railroads contributed to the U.S. economy in the nineteenth century, into a book.

From the outset, Railroads and American Economic Growth was a sensation. It not only challenged the standard thinking that railroads were indispensable to America's expansion, but did it by creating a parallel universe in which railroads didn't exist— and posited that without railroads, the economy in 1890 would have been slowed by only one year. While economists called the book brilliant, Fogel notes, "the historians said, 'This man is an idiot.' " That may have been in part because Fogel pointedly attacked some of the most distinguished railroad historians and their antiquated approach—which Fogel now calls "the excesses of a young person."

Nonetheless, Railroads got Fogel his first professorship, at the University of Rochester, and his second, at the University of Chicago. And it led many people to see cliometrics as an important innovation, Boyer says. "My guess is that he wanted other people to study this, and boy, he got his wish. All of a sudden people started studying the effects of railroads in Britain, Germany, Argentina—and all because Robert Fogel wrote this book."

Ten years later, Fogel and Engerman's work on slavery had an even bigger ripple effect—this time by accident. He and Engerman, a fellow Johns Hopkins grad student, planned to write an article in which they suggested a future project for other economic historians: to show how much less efficient slave labor was compared to wage labor. "A lot of us, including me, believed that a system as evil as slavery could not have been profitable," Fogel says. To illustrate it, they did a back-of-the-envelope calculation. It took them two weeks, working from published census data.

To their astonishment, they found that the South was 6 percent more efficient than the North. "We said, 'That is a crazy result,'" Fogel remembers. "'What did we do wrong? We made too many shortcuts, we have to do it again.'" They spent three months revising the calculation—no longer assuming, for example, that cattle in the North and South weighed the same. The northern cattle were actually heavier, Fogel says. "Instead of counting heads, we had to count pounds." They combed through a variety of sources—from a plantation owner's journal to census material on Southern farms—to compile such data as the prices of slaves in New Orleans, the course of cotton prices from 1802 to 1861, and the average daily food consumption of slaves and of the general population in 1860. Their findings led them to question what had been unassailable truths. "At various points, we were so stunned by the results of what the other was working on that Stan and I were each prepared to accuse the other of finally having succumbed to racism."

They debated how to present the incendiary findings. Engerman voted for modesty, Fogel for candor. Fogel won. In the book's prologue he called their work "corrections" to the vast literature on the slave economy, and listed ten bold propositions, such as that slaves received 90 percent of the income they produced, and that they were better fed and worked less than free industrial workers. The day after the book was published, the authors were flooded with interview requests from the U.S. and Europe. Historians didn't know what to make of the statistics and math; economists accused them of faking data and seeking publicity; civil rights activists called them apologists for slavery. "We had crossed all the ideological wires," Fogel says. "It was not left, it was not right. They didn't know what to make of the argument. Were we anti-slavery or pro-slavery?"

To back up their claims, the pair later turned the footnotes detailing their evidence and analytical techniques into major articles and ultimately the four-volume work Without Consent or Contract: The Rise and Fall of American Slavery, published from 1989 to 1992. As others picked apart their research paragraph by paragraph, it sparked interest in the subject matter, with many of the top quantitative economic historians exploring antebellum issues such as the economics of slavery, sharecropping, and Reconstruction. The combination of Railroads and Time on the Cross put cliometrics on the map, Boyer says. "We're a small field. But we'd be a lot smaller if it wasn't for Robert Fogel."

Marxism and Communism loomed large in Fogel's world, even before he was born. The outbreak of the Russian Civil War prompted his parents to flee from Odessa in 1922. An affluent family, they bribed their way to Constantinople, where his father almost died of typhus and gangrene. Having spent most of their money to keep him alive, the Fogel family arrived at Ellis Island in steerage. Robert was born four years later. For a time the family lived in a tenement on Manhattan's Lower East Side that lacked electric lights; they later moved to the Bronx. "Although I lived through the Great Depression, I remember it as a golden age, because I knew I was loved," Fogel says.

Fogel has said his greatest intellectual influence was his brother Ephim, who was six years older. (Ephim Fogel would join Cornell's faculty in 1949 and chair the English department from 1966 to 1970.) Robert Fogel remembers lying in bed at night listening to Ephim and his friends debate what to do for a date when one had only a dime, as well as ask questions about the economy and politics. For a date, visit a girl at her babysitting job. For the rest, "They said, 'The answers to all that are in Marx,'" Fogel remembers. "For years after that I thought Marx must be the name of an encyclopedia." The U.S.S.R. was an American ally then, and Hollywood films framed Communists as freedom fighters while newsreels lauded the heroic struggles of the Russians beating back the Nazi invasion during World War II. "Marxism was colorful," Fogel remembers. "It was the snobbery of the young intelligentsia to know these arcane works about the analysis of capitalism and its imperfections." By the time he entered Cornell in 1944, he was a devoted Marxist.

It was an ironic philosophical choice, given his father's capitalist success. By then his father, an engineer by training, owned a profitable meat wholesaling business. "I didn't become a radical through my own experience of how terrible capitalism was—it was purely intellectual," Fogel says. "I was a rich boy, the son of rich parents. And I believed that Marxism was the science of society and Marxists were the social scientists of the time." He joined the University's chapters of the NAACP, American Youth for Democracy (the Communist Party's youth wing), and the Young Progressive Citizens of America, and also chaired the Marxist Discussion Group. He spent half of his sizable allowance to bring radical speakers to campus. "My father thought American capitalism was God's gift to the Earth," Fogel says. "I had a big argument with him about how capitalism corrupts and oppresses people. He said, 'Look at me, I came here with nothing. Anyone who works hard and who is bright can make a good living in America.' And I said, 'No, Papa, you're the exception that proves the rule.' Sometime afterward he said his attitude toward me was that with some kids, it's sex, but with me, it was politics—and he was just waiting for me to grow up."

As the World War II euphoria dimmed, forecasts of another Great Depression prompted Fogel's interest in economics and history, as he wondered why it would be difficult for the country to maintain full employment in peacetime. In his junior year, he switched his major from physics and chemistry to history with an economics minor. After graduation, he turned down his father's offer to work in the family business. Instead, he took an unpaid position in Harlem with American Youth for Democracy, where he met his future wife, Enid Cassandra Morgan. A Sunday school teacher from a family of activists, she headed a Harlem youth group that supported 1948 presidential candidate Henry Wallace, who campaigned for voting rights for blacks, universal health insurance, and an end to segregation. Fogel and Morgan married a year later and had two sons.

As the World War II euphoria dimmed, forecasts of another Great Depression prompted Fogel's interest in economics and history, as he wondered why it would be difficult for the country to maintain full employment in peacetime. In his junior year, he switched his major from physics and chemistry to history with an economics minor. After graduation, he turned down his father's offer to work in the family business. Instead, he took an unpaid position in Harlem with American Youth for Democracy, where he met his future wife, Enid Cassandra Morgan. A Sunday school teacher from a family of activists, she headed a Harlem youth group that supported 1948 presidential candidate Henry Wallace, who campaigned for voting rights for blacks, universal health insurance, and an end to segregation. Fogel and Morgan married a year later and had two sons.

At the time, New York was semi-segregated, making life difficult for the interracial couple. Some restaurants would not serve them, and some department store personnel refused to let Enid try on clothes. Blacks and whites alike would stare at them when they held hands on the subway. "But we never had any doubts," Fogel says. "We knew we loved each other." He has written that Enid was both his most confident supporter and keenest critic. "No individual has done more to help me pursue a career in science than my wife." She was associate dean of students at the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business and dean of students at Harvard's summer school, but she often put his career before her own. Friends say Fogel was devastated by his wife's death in September 2007.

Fogel worked for American Youth for Democracy for five more years, earning $50 per week when the organization could pay him. But as Marxists' predictions of severe unemployment failed to materialize, he began to question if they understood capitalism at all. "They couldn't even get a business cycle forecast right. They were Johnny One Note," Fogel says, referring to a 1937 show tune. "The one note was, 'It's going to get terrible.' And if it didn't get terrible, they didn't have an answer." In 1956 Fogel left the Communist Party and enrolled at Columbia, borrowing money from a Cornell friend to pay tuition. "I decided that I wanted to go back to school," he says, "because I had glibly accepted a lot of things."

Now eighty-one, Fogel has the health troubles typical of his age. He walks with a cane, has hypertension (kept in check with medication), and probably should lose a few pounds. But he works full-time—albeit seventy hours a week rather than eighty—and is writing two books, Enid and Bob: An American Odyssey (a memoir) and Simon Kuznets and the Empirical Tradition in Economics. He calls himself a prime example of technophysio evolution, a process that he and Dora Costa, an MIT economics professor and his former student, say is the result of synergy between technological advances and physiological improvements. The theory suggests that over the past 300 years, human biology has changed, with people in the industrialized world becoming taller, stronger, and better able to resist disease. It's one of the many findings to come out of the Center for Population Economics, which the University of Chicago established to lure him back from Harvard in 1981.

Since then, his Union Army work has expanded in many directions, with unexpected findings. A major surprise is that children exposed to unhealthy environments—even in utero—had a higher risk of chronic health problems later in life. The most recent grant will allow the researchers to build on another discovery: that Americans in the countryside lived much longer than those in urban areas. The bigger the metropolis, the sooner the veterans died— by as much as eighteen years for large cities like Philadelphia and New York. "We just stumbled on that by accident," Fogel says. "We realized, my God, the cities were death traps." The grant will also expand the research to collect and analyze data detailing the aging process for the "oldest old"—those who lived to ninety-five—during the first half of the twentieth century. The results may affect issues like financing health care and retirement, and other topics debated not just by economists but medical researchers, epidemiologists, and demographers. "Every year," he says, "we get stunned by something we never anticipated."

But ultimately, Fogel says, his expertise is not in crunching numbers but in finding the right numbers to crunch. Engerman, now an economics professor at the University of Rochester, says Fogel's strength lies also in his persistence. "He would always push at the evidence as hard as he could to see what arguments could be made," Engerman says. "He never accepts the first answer, or the easy one.