When Janice Perlman ’65 first studied the favelas of Rio de Janeiro in the late Sixties, it was rare for an American academic to visit them, much less live there. Her groundbreaking 1976 book, The Myth of Marginality, upended long-held notions about the settlements, which were considered dangerous dens of social ills. Now, Perlman has revisited many of the same people and places for her new book, Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro.

When Janice Perlman ’65 first studied the favelas of Rio de Janeiro in the late Sixties, it was rare for an American academic to visit them, much less live there. Her groundbreaking 1976 book, The Myth of Marginality, upended long-held notions about the settlements, which were considered dangerous dens of social ills. Now, Perlman has revisited many of the same people and places for her new book, Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro.

A pioneering researcher returns to the favelas of Rio

By Beth Saulnier

Whatever image is conjured up by the phrase "international agent of subversion," it doesn't much suit Janice Perlman '65. But when the gregarious blue-eyed blonde was doing research for her doctoral dissertation in Rio de Janeiro in the late Sixties, the Brazilian military dictatorship tagged her with that very label—or, as she calls it with a laugh, "a great honorific."

As a graduate student in political science at MIT, Perlman spent eighteen months living in the city's favelas, the squatter settlements that housed the millions of migrants who'd come to Rio from rural areas in search of a better life. She was finishing her field work when the government passed a law forbidding foreign researchers from taking data out of the country. "The dictatorship was extremely brutal; many people were killed, tortured, or disappeared," she says. "The government was trying to prevent any knowledge of what was happening inside the country from getting out." So Perlman resorted to some tradecraft worthy of an international woman of mystery. She had her data transferred to a computer tape, which she disguised as a make-up compact and carried in her purse; she asked a friend in the U.S. consulate to ship her original surveys and punch cards home in the diplomatic mail pouch. She then hopped the first flight out of Rio—and shortly thereafter, the shack she'd been living in was ransacked, its floorboards torn up and furniture destroyed in a search for subversive material.

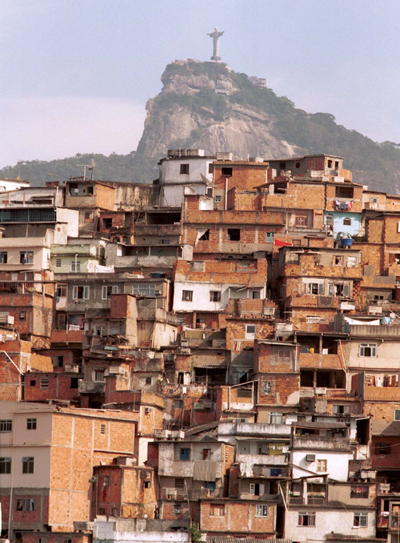

The government, Perlman explains, figured that the only reason a foreigner would live in the favelas was to foment political unrest. But in fact Perlman had been undertaking a seminal study of the dense urban squatter settlements, one that would not only form the basis of her career but prompt social scientists to rethink the favelas themselves. Her research became the subject of her first book, The Myth of Marginality: Urban Poverty and Politics in Rio de Janeiro; published by the University of California Press in 1976, it upended long-held notions about the settlements, which were considered so dangerous that taxi drivers would refuse to stop outside their entrances. "The common opinion was that favelas were absolute dens of crime, violence, prostitution, family breakdown," she says, "that everything you can imagine in terms of social disintegration and dysfunction was concentrated in them."

But Perlman got to know the residents of three favelas, living among them and, with the help of research assistants, conducting detailed surveys of 750 people, each of whom was given a seventy-five-page questionnaire. She recalls her months in the favelas as among the happiest times of her life. "It was beautiful," she says. "It was full of life. The people were wonderful. There was a huge amount of conviviality and laughter." Her book also challenged the view of favela dwellers as mired in poverty, with no ability or inclination to improve their lives. In fact, she says, for many people the lively communities were preferable to isolated, sub-par public housing; residents' greatest fear was that they'd be displaced, since the government had been known to use forcible evictions, demolition, and even arson to erase favelas from desirable land. "My major point was that the people in the favelas were not economic parasites—they were just being exploited, working in jobs no one else wanted, for salaries no one else would accept," she says. "They were considered marginal to society, living on the outskirts; not having apartment buildings or addresses, they weren't even on the map. They weren't seen as human beings with potential to contribute to the city."

An anthropology major on the Hill, Perlman fell in love with Brazil while performing in a musical theater tour of Latin America the summer before sophomore year. The nation, she says, "was in a big political transition, and everyone was talking about the rights of the poor and excluded." She returned on a grant to study in an isolated fishing village—it was a total language immersion, since no one spoke English and Cornell didn't offer Portuguese—where she examined how the youth developed their world view and future aspirations. "They'd just gotten the transistor radio, which brought them the first news of the outside world," she recalls. "All the young people wanted to go to the big city, where the action was. I realized this migration from rural to urban was going to be the big story of my life. So I started studying these migrations, and the favelas are where these people ended up."