![]() The Lab of Ornithology's new coffee table book captures the sounds of more than 700 species

The Lab of Ornithology's new coffee table book captures the sounds of more than 700 species

The Lab of Ornithology's new coffee table book captures the sounds of more than 700 species

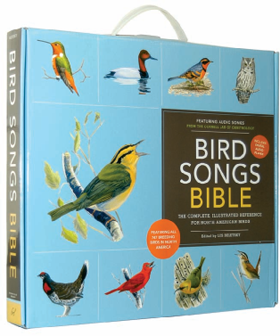

The latest book from the Lab of Ornithology could be a field guide . . . if you're a giant. Published this fall by Chronicle Books, the hardcover Bird Songs Bible weighs in at ten and a half pounds, is two inches thick, and even comes with its own carrying case. It covers all 747 breeding birds in North America— not only their images and vital statistics, but most of their songs as well.

Organized by region, the $125 coffee table book includes a built-in MP3 player with 728 individual recordings, most taken from the lab's Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds. To summon up a clip—the call of an alarmed female spectacled eider, say, or a blue-throated hummingbird in song—the user punches a three-digit code into the number pad. "There's no fuss, no muss," says Greg Budney '85, the library's curator of audio. "You don't have to load a disk or go online and access a file. You have these wonderful portraits, many of which are almost life-sized, and a player that is thoughtfully executed, so you can access the sounds rapidly." In the genre of audio bird books, he says, "this is probably the best user experience to date."

Some two years in the making, the hefty volume includes hundreds of original paintings of the birds, as well as information on their geographic distribution, habitat, and behavior. Budney hopes that the finished product will appeal to a wide audience—and with its vibrant images and interactivity, he sees it as a great way to get children interested in nature. "As beautiful as the illustrations are," he says, "the element that really transports you is the fact that you can make the voice come alive as though the bird were sitting there on the table beside you."

Some two years in the making, the hefty volume includes hundreds of original paintings of the birds, as well as information on their geographic distribution, habitat, and behavior. Budney hopes that the finished product will appeal to a wide audience—and with its vibrant images and interactivity, he sees it as a great way to get children interested in nature. "As beautiful as the illustrations are," he says, "the element that really transports you is the fact that you can make the voice come alive as though the bird were sitting there on the table beside you."

For Budney, choosing the audio clips meant diving deep into the collection of the Macaulay Library, the world's largest repository of animal sounds and video. For example, the library has more than 800 recordings of the red-winged blackbird, which is found throughout the U.S.—so which regional "dialect" should represent the species? "Most of the recordings were already in the library," he says, "but what hadn't been done was going through the multiple examples that might exist for a species and determining, say, the best 'witchity-witchity' call for the common yellowthroat that fit the running time."

In addition to choosing the clips, Budney and his colleagues faced the challenge of squeezing them all onto the book's memory chip. Although most last less than fifteen seconds, that still meant some serious data compression. "And when you data compress, you're basically throwing bits of information out, and that can dramatically affect the fidelity of the sound," Budney says. "The resulting product, if not dealt with carefully, can sound pretty abysmal." Making it work, he says, required an understanding of human psychoacoustics. "What bits of information does the human ear need to receive," they asked themselves, "for this to sound like what we might hear outdoors?"

{youtube}1X5WMu_oJnQ{/youtube}

The Language of Birds (9:42)