When the Moosewood Restaurant served its first meal thirty-eight years ago this month, the owners were still trying to figure out how to run the steam table (and the entrée was two hours late). But with a menu of tasty vegetarian cuisine, plus the success of the Moosewood Cookbook, the humble Ithaca eatery has grown to be one of the world’s most famous natural-foods restaurants. Now, Cornell’s Rare and Manuscript Collections is home to Moosewood’s historical archives—a trove of photos, business papers, fan mail, and much more.

When the Moosewood Restaurant served its first meal thirty-eight years ago this month, the owners were still trying to figure out how to run the steam table (and the entrée was two hours late). But with a menu of tasty vegetarian cuisine, plus the success of the Moosewood Cookbook, the humble Ithaca eatery has grown to be one of the world’s most famous natural-foods restaurants. Now, Cornell’s Rare and Manuscript Collections is home to Moosewood’s historical archives—a trove of photos, business papers, fan mail, and much more.

The University acquires the archives of the famed Moosewood Restaurant

By Beth Saulnier

Josh Katzen '70 is a Boston-area real estate developer. He holds a law degree from Penn. He has, as he puts it, "a lot of conservative activities on my résumé." When he was hired to teach real estate at Brandeis, he recalls, those right-leaning credentials ruffled some feathers. "Some professors were saying, 'Why is he here? He's a Zionist, conservative, right-wing guy,'" Katzen remembers. "And then somebody finally says, 'Look down his résumé. He started the Moosewood Restaurant. He might be OK.'"

Nearly four decades ago, Katzen and a handful of friends took an empty space on the bottom floor of a former junior high school in downtown Ithaca and created what would become one of the world's most famous natural-foods restaurants. A local carpenter built the original thirteen tables in exchange for free meals; a friend sewed the batik curtains. The idea, he says, was to create something warm and welcoming—the opposite of the stereotypical, self-serious vegetarian eatery that was the culinary equivalent of a hair shirt. "We served beer," he notes. "We definitely did not do seaweed."

It wasn't until shortly before it opened—on January 3, 1973—that they finally settled on a name for the place. They called it Moosewood, after the dog in Hugh Prather's trippy self-help book, Notes to Myself. "There were a lot of guys with ponytails and colorful clothes," Katzen recalls. "It was a very friendly place. Everybody knew everybody. It was like living the cover of a record album—like, 'Our house is a very fine house.' That's what Ithaca was like in those days, and Moosewood was the place everybody came."

Flash forward thirty-eight years. Moosewood, now tripled in size, is still doing a brisk trade in Ithaca's Dewitt Mall—no small feat in the notoriously Darwinian restaurant industry. The Moosewood Cookbook, that landmark guide to vegetarian cuisine written by Katzen's sister and fellow Moosewood founder Mollie Katzen '72, has taught generations of twenty-somethings how to tell their tofu from their tabouli. Subsequent cookbooks—penned by the restaurant's current owners, known as the Moosewood Collective—have become best-sellers and twice won the James Beard Award, the genre's Oscar. Bon Appétit called Moosewood one of the thirteen most influential restaurants of the twentieth century. A line of Moosewood-branded foods, including frozen soups and entrees, is sold in upscale supermarkets around the country. In short, the Moosewood name has spread far beyond one small Upstate New York city— occasionally rivaling a certain university on the Hill for bragging rights as Ithaca's most famous institution. "Whenever I travel anywhere and I mention I'm from Ithaca, half the people who recognize the city's name will say 'Cornell,'" says University Librarian Anne Kenney. "But equally as many will say, 'Oh yeah, Moosewood Restaurant.'"

Like chickpeas and tahini, Moosewood and Cornell go way back. In addition to the Katzens, many of the founders (and several current members of the nineteen-person collective) are alumni. Faculty and staff have always comprised a hefty portion of the restaurant's customer base, and Moosewood is a go-to spot for legions of visiting parents. (Just try getting a table on Commencement Weekend.) "Ithaca and the Cornell community have contributed to our success because they're populations that are adventurous when it comes to food," says Joan Adler '72, a collective member who started working at Moosewood as a waitress in 1974. "If it weren't for our regular diners we wouldn't have been able to try everything we've tried."

Last year, those town-gown ties became more formalized, when the Moosewood Collective made Cornell's Rare and Manuscript Collections the official repository of its archive. Housed in four boxes in Kroch Library—two full filing boxes and a couple of oversized containers for large-format items—the archive contains a wide variety of material, from vintage photos and early menus to handwritten cookbook drafts to glossy mock-ups of product packaging. "There's so much in those four little boxes," says Kroch curator Brenda Marston. "There are records of a local business, and there's the whole angle of their success as a collective. They represent that movement in the Seventies to think about different ways of doing everything. There was such a desire to try new ways that were less hierarchical. And what's great about their story is that they were successful as a business, too."

Marston and others see the archive as appealing to scholars interested in everything from local history to the evolution of vegetarian cooking to the joys and pitfalls of collective ownership. "This is a great case study of a bunch of people who didn't have much experience but learned to run a business, one that has been successful for going on four decades," says Hotel professor Mary Tabacchi. "That's a food and beverage entrepreneurship story that has to be told, and the papers are there for someone who wants to do it."

But you don't have to be an academic to graze the archive's offerings. Like all of Cornell's collections—the University has world-class holdings on topics from Icelandic sagas to the French Revolution to hip-hop music to witchcraft—it's available to everyone. "We're open to the public," notes University Archivist Elaine Engst, MA '72. "You don't need to be a serious scholar to look at this. You just have to be interested." After making a request in advance, you take a trip underground to Kroch— accessed through Olin—stash your belongings in a locker, and enter the Rare and Manuscript Collections' reading room, a meditative space where pens are banned but pencils are kosher.

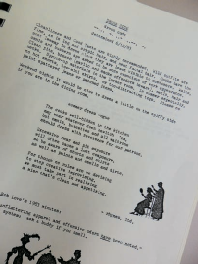

An Eighties-era policy manual advises, 'Try to be polite to take-out customers even if they're not deserving of it and it's a drag.'Even a cursory poke around the Moosewood collection yields a treasure trove of memorabilia, a colorful peek into the not-so-distant past. One of the favorite items among the archives' staff is a document from the mid-Eighties entitled "The Moosers' Book of Harmonious Functions or, More Succinctly, Moosewood Policy Notebook (and More)." The manual is a combination of practical edicts ("no bikes in the locker room"), legalese (procedural rules and bylaws), and quirky gems ("try to be polite to take-out customers even if they're not deserving of it and it's a drag")—capturing the ethos of a group of people trying to run a business with progressive principles in a particular time and place. Witness the official Moosewood dress code, as determined on June 12, 1983:

Cleanliness and good taste are highly recommended. Wild outfits are fine, as is leg and armpit hair, and neat facial hair. Cooks have the most leeway in dress since they are least visible to customers. Waits, omnis, and bussers are asked to be more conscious of work appearance. Clean pits, breath (garlic and smoke offenders beware), nails, hair, and necks. Spruce-up materials in the locker room. In summer especially, no hot shorts, too-mini skirts, or too-distracting tops. Please no paint-spattered jeans or patched items. Weekend nights it would be nice to dress a little on the spiffy side if you are in the dining room.

Of course, many restaurants have policy manuals (though most aren't anywhere near as entertaining). But how many have a handwritten guide to waitressing that advises against letting customers over-order, since it's unethical to waste food? Or keep a journal in which staff members record restaurant-related dreams? The archive includes excerpts from the latter, including this one, by a woman named Susan:

I was in the dining room at night, waiting on tables, with that weird fishbowl feeling when it's dark outside. All of a sudden sirens and church bells sounded all over town. Everyone went outside and there was a parade—Albert Einstein was waving from a float. He was covered with leis of flowers and he was beaming. It seemed that world peace had been declared and we all felt quite excited and hopeful and relieved. Then it was announced that everyone in the world had to adopt an orphan baby and we were all to report immediately to the Women's Community Building to receive the children chosen for us. So workers and customers forgot about dinner and we lined up before a conveyor belt which the babies were coming down. Flora was ahead of me in line and she was given a baby orangutan, which I knew was intended for me. I recognized this as my real child, but she wouldn't trade.

The archive also contains dozens of thank-you letters and pieces of fan mail from around the world (including a note from Fred Rogers on official "Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood" stationery). A 1996 postcard from a couple on vacation at Lake Titicaca opens, "Dear Moose, Please do not let this go to your heads…" and goes on to describe meeting an English couple living in Chile. "When we exposed ourselves that we were from Ithaca," it reads, "they immediately asked us if we knew the Moosewood."