Today, Grabbe has graduated from snakebite victim to doctor in charge. She organizes students into groups: some prepare for McStay's arrival, some for Edelstein's, and a few are assigned to row out to retrieve the patients. They find them in the chilly water thirty feet from shore; the rescuers have no choice but to jump in, helping them to shore and stabilizing their spines on the frigid, slippery, guano-covered rocks. The rescuers eventually load them into the boats and bring them back to the camp, where the students have gathered wood to make a lakeside fire. A shivering McStay is found to have a dislocated shoulder, while Edelstein's condition is more serious; she may have spinal damage. The student doctors aim to have her airlifted, but Gaudio nixes the possibility, upping the stakes. "There's been a pileup on I-90," he tells them. "All the helicopters are being used for that." Informed that no rescue is available for twenty-four hours, the students set about stabilizing the patients. Afterward, during the feedback session, Lemery notes that although their performance was good, they made one obvious mistake. "There were two patients on the dock and a beautiful fire," he says, "and they didn't come together for at least twenty minutes."

The final scenario, back at Camp Dudley after the group returns from canoe-camping, proves to be even more wrenching. Three victims are struck by lightning; one has only minor injuries but is visibly agitated, a second suffers cardiac arrest but is revived, and a third has a spinal injury—and ultimately dies. "We never really talk about death in the back country, but it's an important topic," says McStay. "Most of the time when you're hiking, you're with people you know. When I take care of people in the emergency room who die, I have no emotional connection with them— but if you're in the back country, chances are that you do. That complexity is the final thing that we cover. It's probably the most emotionally charged and most difficult." In that scenario, the student doctors do CPR on the dying victim for about half an hour, to no avail. "At some point, there's a conversation about what to do next. 'Do we keep doing CPR? Do we stop?' " McStay says. "Every year somebody cries or gets angry that we've stopped— they were friends and we should keep going."

In addition to offering practical training in back-country medicine, participants say, the trips have an important fringe benefit: getting time-crunched medical students and professors out of the city for a week. In fact, one of the research projects being conducted by Lemery and Gaudio is on the protective effect of outdoor education on mental health, comparing Cornell freshman surveys to diagnostic codes in a double-blind study. "We always say that a huge part of what we're doing is getting people out so they can see the link between the outdoors and health and wellness," Lemery says. "Historically, doctors take care of themselves horribly. So that's a big component of it, acknowledging that there's a tremendous amount of stress, from being a medical student to a resident to an attending." Although Camp Dudley is just an afternoon's drive from Manhattan, in some ways it feels like another planet. The fresh air, the silence, the open space, the greenery, the blue water of Lake Champlain—it's light years from the noise and bustle of the city, not to mention the pressure of medical school. "In third year, you're in the hospital all day and then you go to the library," says Santos. "You don't leave the little radius of the hospital. There are studies showing that medical students are sodeprived of sun that they are vitamin D deficient. It gets that bad."

GET OUT

At Cornell Outdoor Education, nature is the classroom

In Last Child in the Woods, author Richard Louv describes a condition called "nature deficit disorder." As Cornell Outdoor Education (COE) director Todd Miner describes it, "Kids these days, who average thirty hours a week of screen time— whether that's TV, computers, whatever—are not getting outside and exploring the woods. Louv claims that everything from ADD to the rise in asthma and obesity can be at least partially traced to the fact that kids spend way too much time indoors." Miner sees COE as an antidote, connecting people to the environment— both for their own physical and mental health and to provide the next generation of environmental leaders.

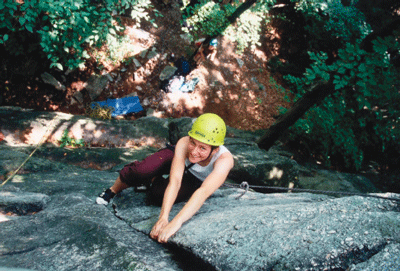

Each year, about 2,500 Cornell students participate in COE activities, which range from basic hiking and paddling to more advanced outings like ice climbing and whitewater rafting. With an annual budget of $1.2 million—funded, in part, by course fees—COE also offers a wilderness-based orientation program for new students, courses in outdoor leadership, and training in everything from nature photography to back-country first aid. "Our goal is to touch every Cornell student, though we're a ways from that now," says Miner. "We want to make COE like waiting in line for hockey tickets or climbing the bell tower or eating at the Hot Truck—that you can't say you graduated from Cornell without doing something with COE." Many courses can be taken for physical education credit, others just for fun. Some—like a backpacking tour of Utah canyon country, a tree climbing trip to Costa Rica, or a dogsledding and skiing expedition in northern Minnesota—are held over school breaks. COE's facilities include two rock climbing walls, two challenge courses, and an equipment rental center open to the public. Says Miner: "We're arguably the largest university-based outdoor education program in the country."

COE's participation is key to the Medical college's wilderness medicine program; according to emergency medicine professor Jay Lemery, such a joint effort between a medical school and an outdoor education program is unusual, if not unprecedented. The collaboration dovetails with efforts in recent years—especially since cardiologist David Skorton became president of Cornell—to strengthen ties between the New York and Ithaca campuses. "COE has the expertise in wilderness skills, staff, equipment, and logistics, and we know how to put together outdoor expedition programming—what we lack is wilderness medicine expertise," Miner says. "On the other side, Weill has incredible expertise in emergency, disaster, wilderness, and environmental medicine, but not a whole lot of hands-on outdoor skills and experience, and it doesn't have the logistical system in place. Bring the two together, and we've got both sides fully covered."

PHYSICIANS, AL FRESCO

Why wilderness medicine is on the rise

With growing interest from students and an active professional association—the 3,000-member, Utah-based Wilderness Medical Society—wilderness medicine is a burgeoning field. Emergency medicine professor Jay Lemery, an alumnus of Dartmouth Medical School who grew up in the Adirondacks and founded the program at Weill Cornell, cites a variety of trends that have sparked interest in wilderness medicine, from increased concern about the environment to a tendency for Baby Boomers to continue their outdoor pursuits into their later years. "They're still active, but they have diabetes and congestive heart failure and all of those other things," says Lemery, who has been spearheading efforts to establish a fellowship in wilderness and environmental medicine at Weill Cornell. "So the type of person who is going out into the wilderness is someone who may have less physiological reserve." Another factor is a demographic trend that Lemery jokingly calls "the dumbass effect." "It's the whole X Games generation, people doing extreme sports or adventure races—weekend warriors, ultra-marathoners, things like that," he says. "We're seeing more of that, which is a medical niche that needs to be filled. Who's taking care of these people?"

Finally, he notes that increased interest in wilderness medicine reflects the growth of two related fields: disaster response and international medicine. "For those of us who were in September 11 and Hurricane Katrina, we know that our approach to treating patients was not like anything we'd ever learned," he says. "The skills we teach in wilderness medicine are how to improvise, to think beyond the algorithm, to look around and make clinical decisions based on what you have in front of you—that's disaster medicine in a nutshell." The same applies to international medicine; as more students spend time in the developing world, he says, the lessons gleaned from wilderness medicine are invaluable. "What are students going to know if their entire medical training has been in NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital and they show up at a clinic and are told, 'Here's a pair of rusty scissors, a roll of duct tape, and half a bottle of penicillin. We're happy to have you here—and by the way, there are 500 patients waiting for you'? What is that student going to do? The things we teach give them a place to start—to know there are lots of different ways to approach patient care, and that there's a real science to treating someone in an austere environment."