In September 1933, Millie Uher made the ten-mile trip from Myers, New York, to the Cornell campus. She was the first in her family to go to college and—despite having excelled academically and athletically at Lansing High School—she enrolled at the University without the blessing or support of her immigrant father.

In September 1933, Millie Uher made the ten-mile trip from Myers, New York, to the Cornell campus. She was the first in her family to go to college and—despite having excelled academically and athletically at Lansing High School—she enrolled at the University without the blessing or support of her immigrant father.

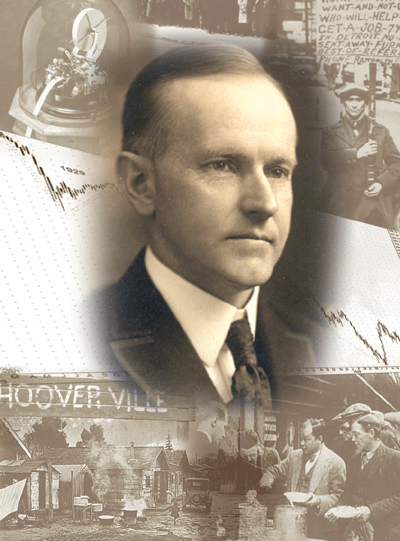

How the 30th president can help us reinvent the American Dream

By Richard Marin

In September 1933, Millie Uher made the ten-mile trip from Myers, New York, to the Cornell campus. She was the first in her family to go to college and—despite having excelled academically and athletically at Lansing High School—she enrolled at the University without the blessing or support of her immigrant father. He had worked twenty-five years in the rock salt mines and had saved enough to buy his own home as well as enough extra land to farm and open a gas station and roadhouse on Route 34B. He even donated land for his local church.

The story of the family of Ludmilla Uher Jenkins '37—my mother—embodies what most of us think of as the American Dream: a house, a business, prosperity derived from hard work, and generational advancement. Indeed, if you Google "American Dream" you learn that this catch-phrase was coined in 1931 by James Truslow Adams in his book The Epic of America. Adams, an investment banker turned writer, declared that with enough hard work and good fortune, anybody could achieve what they wanted in life. He wrote: "There are obviously two educations. One should teach us how to make a living and the other how to live."

I am an investment banker turned writer and teacher. After graduating from Cornell with a BA in 1975 and an MBA a year later, I went to Wall Street to make my living. After thirty-two years of commercial, merchant, and investment banking, I ran aground and have only now resumed learning how to live. As CEO of Bear Stearns Asset Management, I presided over the first hedge-fund bungalow on the beach to be hit by the great financial tsunami that continues to thrash the economic world. So I have moved on to use my skills in different and yet similar ways: I consult, I am launching new businesses on Wall Street, and I teach a practicum at the Johnson School.

After the events of the past year, I am haunted by the need to put the current prospects for the American Dream in perspective. More than ever, we all need to believe in and stand for something. Is that entitlement to prosperity? Consumerism has certainly run rampant of late. George Carlin spent his last days humorously preaching that the American Dream was called that because "you have to be asleep to believe it." He called consumption the new national pastime. He was a funny man—but I suspect he believed in Americans more than his humor would imply. I know I do, so let's see if we can find a reason to be optimistic about the future.

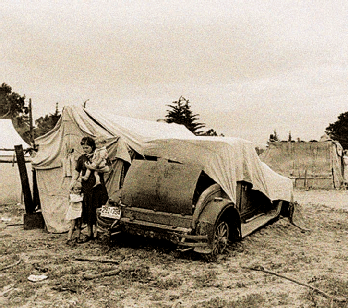

Many people seem to think that the American Dream is all about prosperity, success, and wealth. Art Laffer, the Reagan-era supply-side economist, epitomizes the heady chapter that now seems to be closing, and he recently editorialized in the Wall Street Journal that "the age of prosperity is over" and that George Bush will be likened to Herbert Hoover as we sink into a new depression.

Barack Obama ran for president by admonishing us to reclaim the American Dream. He developed this theme well before the financial crisis engulfed us. How prescient to invoke a cry for an economic and spiritual rally for the benefit of a broad array of citizens at a time of great but precipitous prosperity during which more Americans than ever enjoyed (no matter how briefly) the dream of home ownership. In 2003, Congress passed the American Dream Down-Payment Initiative to insure just that. Obama was foreseeing the repossession of the Dream just as Americans received their election ballots—and their foreclosure notices.

Barack Obama ran for president by admonishing us to reclaim the American Dream. He developed this theme well before the financial crisis engulfed us. How prescient to invoke a cry for an economic and spiritual rally for the benefit of a broad array of citizens at a time of great but precipitous prosperity during which more Americans than ever enjoyed (no matter how briefly) the dream of home ownership. In 2003, Congress passed the American Dream Down-Payment Initiative to insure just that. Obama was foreseeing the repossession of the Dream just as Americans received their election ballots—and their foreclosure notices.

Herbert Hoover had a much less ambiguous war cry. He ran for president in 1928 with the promise of "a chicken in every pot and a car in every garage." This was a trend-following pledge after a decade of unprecedented economic progress under President Calvin Coolidge, during which U.S. per capita income grew by 37 percent, auto production grew eight-fold, the national debt fell by 36 percent, taxes were reduced by 20 percent, and stocks appreciated by 256 percent. We all know how that story unfolded.

Wall Street Crash Course

Wall Street always strives to predict the future— but it is often forced to use historical information and quantitative measures (leavened, one hopes, with a modicum of judgment) to make what are informed bets. It is therefore not unusual that when a financial crisis of biblical proportions finds its way to our door— via the Street—that we look to history for precedent.

The financial and popular press have been filled with references to the Crash of 1929 and the Great Depression as we seek a comparable time and circumstance to compare, contrast, and mollify our sense of the danger that lies ahead. But all of this conjecture and concern seems to miss the real point of the American Dream. It may be about prosperity and wealth—but it is more about thrift, hard work, independence, and economic justice.

At this point, we need to think less about Herbert Hoover and more about Calvin Coolidge. "Silent Cal" was known for his parsimonious ways and his conservative-but-just manner. During his laissez-faire years in the White House (1923-29), the nation's economy grew more than at any time in American history, before or since. This era of economic awakening was characterized by a blend of industrialization, consumerism, and broad-based economic well-being. And Coolidge himself stood for honesty, decency, thrift, the work ethic, and a long list of other values that have the common element of striving for the greater good of the American people.

Many think that the excesses of the "Roaring Twenties" and the speculative bubble on Wall Street are what caused the Crash and the Great Depression. Bubbles pop and there are consequences, right? This satisfies our collective sense of cause and effect. But it just isn't so.

Cornell's Hal Bierman, the Noyes Professor of Business Administration, writes in The Great Myths of 1929 and the Lessons to Be Learned about "rational price bubbles." He says that "there were solid reasons for buying stock in October 1929, but market sentiment soon shifted from optimism to pessimism, and the negative psychology of the market became more important than the underlying economic facts."

Other recent studies on bubbles would suggest that they are an important and somewhat unique aspect of economic development. Daniel Gross '89, a financial writer for Newsweek, has written Pop: Why Bubbles Are Great for the Economy, in which he addresses the infrastructure building they bring about. Tom Friedman also mentions the issue in The World Is Flat, when he quotes Bill Gates on the Internet bubble and the network infrastructure it created, and why it formed the foundation for the next significant stage of growth of the technology economy. Indeed, bubbles may advance the American Dream more than retard it.

Coolidge set the stage for what could have become one of the golden ages of American economic history, rather than one that would sink it into depression. As Hal Bierman has noted in his books on the Crash, the causes had less to do with economic fundamentals or speculation than with ill-advised monetary and fiscal policy and actions like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, which greatly impeded trade with Europe. Even the regulations enacted to rein in stock speculation may have added to the pessimism that engulfed the market. One is forced to wonder whether if Coolidge had chosen to run again in 1928, his non-interventionist beliefs might have produced a far better outcome—perhaps one that could have built on the prosperity of the Twenties and even on the stock market bubble. One's next thought is whether our new administration will fall prey to the same zealousness practiced by Hoover or learn from history.

We now have a more complex and globally intertwined financial system than in 1929, and our economy is more dependent on that system functioning properly. This is the logic behind the so-called federal bailout and the reason for bipartisan support for what is normally considered an unpalatable level of government intervention.

So where does this lead us as a country—and a world? As part of a global economy, Americans are less concerned about borders and currencies and more about our national values and psyche. Weak dollar = more exports? Strong dollar = less inflation? What we know for sure is that all markets seem to converge and correlate just when we don't want them to. Other countries start to eschew the weak dollar and talk of disconnecting from it—right up until the crisis washes over their shores. Then the U.S. Treasury suddenly needs to increase the money supply to feed foreign demand for the dollar. The U.S. is still the safe haven, and it certainly can't be due to our financial or fiscal prudence. It must be something greater, something to do with our socioeconomic makeup.

Coolidge's Rules

Even today, the thoughts of Calvin Coolidge serve as a guide for the solid and moral path that America needs to follow if it is to re-establish its leadership role. He said that banks were "public institutions… with moral obligations to be administered for the public welfare." This seems quite insightful given the current circumstances. And while no one would accuse Cal of being a socialist, he did feel that "all true Americans are working for each other…serving and being served."

The cycle of fear and pessimism is upon us. What would Coolidge do? He might conclude that large conglomerates have gotten too big and too opaque to manage risks in a manner that protects the public welfare. Nationalization would not be acceptable to Cal; he would rely on natural economic forces. I think his advice would be that once stability was achieved, the economy should regain its footing through economizing, working hard, saving, and—most important—rebuilding capital and trust. That may seem basic, but it's pretty sound as well.

Robert Frank, the Louis Professor of Management at the Johnson School, has written in his books and newspaper columns about the recent narrowing of the wealth gap. He explains that financial asset declines such as the one we are now suffering narrow that gap, which had widened considerably in recent years. It's hard to suggest this as a desirable means of improving ourselves, but it does highlight a silver lining: the economy needs consumerism. George Carlin's rants notwithstanding, social and economic equality hinge on narrowing the wealth gap. In the same way that greed is good in moderation, so is consumption. But this narrowing of the gap is but a pea under the pile of cash-stuffed mattresses that we all feel compelled to sleep on these days. The extent of economic injustice today would have "Silent Cal" reaching for his megaphone, not just because of his social conscience but for its sheer irrationality.

Wall Street needs Main Street: 65 percent of GDP is from consumer spending. And Main Street needs Wall Street—but it needs one that it can trust and that is strong enough to do the heavy lifting for the economy. Wall Street surely must rebuild. The remaining big banks will provide a meaningful and stable base. Look at the example of Bear Stearns becoming a part of JP Morgan: the house of Morgan (founded by one of the great robber barons) absorbs the grittiest broker/dealer and king of subprime mortgage structuring, then launches a trend-setting mortgage modification program to help salvage overburdened homeowners. You can't write fiction that's more compelling and ironic than this. The signs on Park Avenue should read: YOUR TAX DOLLARS HARD AT WORK REBUILDING TRUST.

More than the big banks, it will be independent, imaginative, and hard-working startup boutiques that will reshape Wall Street, and thus the American economy. Many on the Street have known for years that the markets are ruled by the boutiques. Hedge funds have dominated liquid (and supposedly liquid) markets, and private-equity firms have dominated corporate finance. Commercial, merchant, and investment banks have served mostly to imitate and service these mustangs of the financial prairie. Regulators have tried to corral them, only to realize that they are best controlled on the free range. They can maneuver better than any rigidly capitalized and regulated bank. They are wild and tough—but so are the markets they work. And they can "reincarnate" over and over again.

The current shakeout in hedge funds and private-equity shops is just part of the ebb and flow of the market. And their recently mediocre showing in the public markets does nothing but make the point that private capital is their best course and monetization is a "buyer beware" game. These are the dominant movers of the world economy, and they are a primal force for deploying intellectual capital. Time and time again we see that labor and capital are fungible and generally in abundance (even though occasionally in hiding), but that entrepreneurial zeal and high-quality intellectual capital are always in short supply.

Calvin Cake

So here is my version of Calvin Coolidge's recipe, using his own words, for curing post-traumatic financial stress syndrome:

- "Fate bestows its rewards on those who put themselves in the proper attitude to receive them." Stop the madness of pessimistic thinking.

- "Prosperity is only an instrument to be used, not a deity to be worshipped." Spread the wealth, mind the wealth gap, and reinvigorate the consumer (here and abroad).

- "Persistence and determination are omnipotent." Get on with the hard work of rebuilding trust and fiscal soundness. Promote entrepreneurship in finance and investment as well as other sectors of the economy.

- "The real standard of life is not of money but of character." Reward service and long-term value creation, not short-term profitability.

- "The higher our standards, the greater our progress, the more we do for the world." Entrepreneurs are our future, both in America and globally.

Stir gently, bake carefully, let stand for several quarters, and then have your cake and eat it too. This is how we reinvent the American Dream.

Richard Marin '75, MBA '76, is executive-in-residence in asset management at the Johnson Graduate School of Management.