For nearly nine decades, Dale Corson has pursued photography with the eye of an artist and the exactitude of an engineer. Even at ninety-six, the president emeritus is still practicing his craft, and he recently had a solo show at the Kendal at Ithaca retirement community, where he and his wife live. A look at Corson’s work, from nature photography to images of his children to travel shots of exotic locales.

For nearly nine decades, Dale Corson has pursued photography with the eye of an artist and the exactitude of an engineer. Even at ninety-six, the president emeritus is still practicing his craft, and he recently had a solo show at the Kendal at Ithaca retirement community, where he and his wife live. A look at Corson’s work, from nature photography to images of his children to travel shots of exotic locales.

An avid amateur photographer for nine decades, President Emeritus Dale Corson brings a scientist's precision to his artistic passion

By Beth Saulnier

In the Sixties, when the Hill was a maelstrom of heightened emotions and bitter controversy—divisive battles about race relations, turmoil over the draft and the Vietnam war, the upending of long-cherished notions about academia itself—many on campus looked to then-Provost Dale Corson as a voice of wisdom and calm. But where did Corson turn when he needed a respite? "During the bad days on campus, I would often go to my darkroom on Sunday afternoons and lock the door," recalls Corson, who served as Cornell's president from 1969 to 1977. "No one could reach me, even by telephone."

For Corson, photography had long been a source of enjoyment, solace, and inspiration. He caught the bug at age seven, when an aunt taught him to develop the prints she took with a Kodak Brownie box camera. By high school, he had a darkroom in his basement; while in grad school in California in the Thirties, an exhibit of photographs by Edward Weston and Ansel Adams rocked his world. "I was so captivated by those images," he says, "that I resolved to learn how to do work of that caliber."

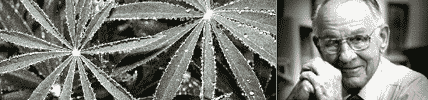

Today, the ninety-six-year-old physicist and president emeritus lives at the Kendal at Ithaca retirement community, where his photographs line the hallways—shots of crocuses, leopards, a 1973 eclipse, a ground squirrel nibbling a slice of water-melon. "He has a real feeling for black and white photography, for tone and hues, light and shadow, the technique of it," says Johnson Museum director Frank Robinson. "He also has a feeling for composition—he does not do just random shots, but he thinks about how it is composed. Technically, he's very careful in terms of the final print. I don't know how this relates to him as a scientist or as a university president, but it's amazing. He's the real thing."

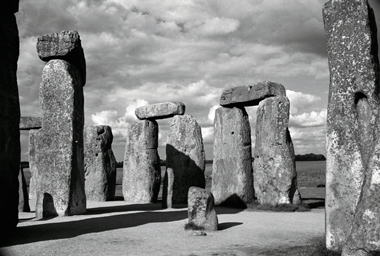

Though Corson and his wife, Nellie, pretty much stay home these days—"I've given up traveling; my wife and I go from our apartment to dinner, that's about it"—over the years the couple traversed the globe, including nine months in China. His collection of more than 25,000 Kodachrome slides and 15,000 black-and-white negatives includes many travel shots—England's Exeter Cathedral, the Acropolis, Kenyan safaris, 2,000-year-old Philippine rice pad-dies, the Taj Mahal. "I can take a piece of the world and see what's really there, not be distracted by clutter in the picture," says Corson, proffering his prize shot of the Indian landmark. "There's not one day in a hundred when you can take a photograph of the Taj Mahal and not have dirty skies, clouds, pollution—whereas this is just a clean, pure picture of the object itself." He waited hours to get the perfect shot of Stonehenge, where the light was just right and there were no visible tourists or cars. "Unfortunately," he says, "I was using the worst lens Nikon ever made."

That's just one of Corson's photographic laments; even decades later, some of the missed opportunities still nag at him. "When I first went to Rome in 1958, I walked all over the city. I cased the joint and looked at the things I'd like to photograph, decided what time of day the light would be the best," he recalls with a sigh. "I went back to those same places at the time of day I had decided and took a whole bunch of pictures, and the film did not advance in the camera. I lost them all, every single one."

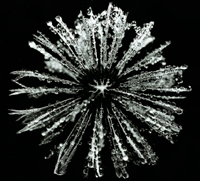

More recently, there was the nature photo that went awry. Corson likes to isolate his subjects via focus, lighting, and framing, and on one expedition he discovered that Mother Earth had done his work for him. "I had a marvelous opportunity in one of the wildflower places around Ithaca," he says. "I got a beautiful flower with the sun shining just on it and not on any background. I took the photo and thought, Boy, I really hit it this time, and I brought it home and discovered I'd forgotten to open the aperture. I would have had a marvelous picture, but it turned out to be a real dud." While Corson shoots in both color and black and white, he prefers the latter; it all comes back to his passion for spare, exact composition. "Most of the great photographs in the world are black and white," he says. "Color is a distraction."

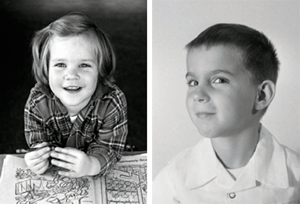

In addition to the dozens of Corson photographs that have been on display at Kendal for years—moving out of a five-bedroom house freed up a lot of framed prints—last spring its community center hosted a retrospective of his work. The images in the show, which ran for three months, ranged from shots of his children when they were little to a continuing series of portraits of Kendal residents taken on their 100th birthdays. "The idea," he says, "is to try to catch something of their character." Corson's work has also been the subject of an exhibit at the Johnson Museum, which devoted three galleries to his photographs several decades ago. In the Seventies, the International Center of Photography included him in an exhibit of talented amateurs, along with the likes of Senator Bill Bradley and actress Gina Lollobrigida. "Dale's work is in a tradition that includes people like Ansel Adams; it has those standards of technical and formal perfection," Robinson says. "His life has been extraordinary, and his work reflects and expresses that life in a perfect way. That's the way it is with an artist—and Dale is a real artist."

Even as he approaches the century mark, Corson has been keeping busy. A few years ago, he helped renovate the sundial on the Engineering Quad; he'd originally designed it, but its mechanism had corroded over time. He collaborated on a multi-media restrospective of his career, The Legacy of Dale Corson, released in 2009, and he's currently working with former dean of the faculty Bob Cooke on a history of the Arecibo radio telescope. And he's still shooting pictures; since moving to Kendal in 1996, though, he's segued to digital photography. After many decades in the darkroom, he relishes the ability to control minute details of post-production via the computer. "The things I've done in the last year are probably better than anything I've ever done before, so it continues to evolve," he says. "I'm still learning."