“This is my first time on stage,” says the man in the bright yellow hoodie. “Oh my God.”

Demetrius Molina stares out at the audience from his unfamiliar perch, not so much a stage as a low platform. Despite his deep voice and neatly trimmed goatee, there’s an oddly childlike air about him: gap between his front teeth, sweatshirt the jolly color of a traffic sign, palpable awkwardness at being on display.

It’s a Monday night in mid-May, the first time that Molina and his fellow cast members have rehearsed in the space where they’ll perform the following Thursday. Alison Van Dyke, a senior lecturer in acting at Cornell, sits in the front row with a script in case the actors fumble a line. Theatre professor Bruce Levitt—red shirt untucked over blue jeans, Mozart hair askew—stands at the back, taking in the action and urging the cast to project.

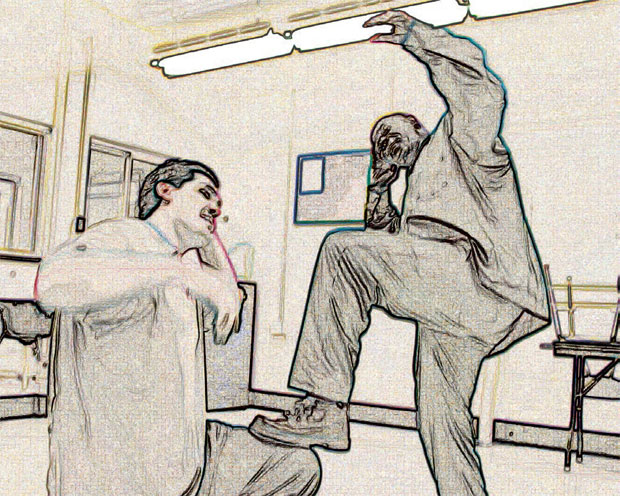

Cornell professor Bruce Levitt in a Phoenix Players Theater Group (PPTG) rehearsal with (from left) inmate Nate Powell, Ithaca College professor Judy Levitt, and inmates Demetrius “Meat” Molina and David Bendezu.

“I’m nervous,” Molina says, to no one in particular.

“Just focus on what you’re doing,” Van Dyke tells him.

He takes a deep breath. “This is a story about life,” he says. “This is a story about love—” Molina stops. “It seems like I’m yelling.”

“No, you’re not,” she assures him.

“I gotta get used to this,” he says.

“That’s why we do it,” she replies, and Molina gives it another go.

For the next ninety minutes, the teachers and actors run scenes and tweak blocking, skipping over some sections and reworking others. It’s a typical rehearsal—except for the countless ways in which it isn’t.

Take the monologue that Molina launches into, about a falling out with his younger sister over her abusive boyfriend. He describes how the man beat her up and got her pregnant, how she wouldn’t leave him despite Molina’s pleas, how the situation escalated to where she helped the boyfriend try to kill him in a drive-by. Although the tale has a happy ending of sorts, it’s bittersweet. Brother and sister mend fences—but their rapprochement comes in the visiting room at Auburn Correctional Facility, where Molina is serving time for murder.

“This is a story about life,” Molina says again, his voice booming to the back row. “This is a story about love. And this is a story about loss.”

At Auburn, there are hundreds of incarcerated lives, and it doesn’t take a sociologist to see that the inmates have experienced—and caused—an immense amount of loss. What’s surprising is that, at least in this room, there’s a fair amount of love.

PPTG member Molina.

The performers are members of the Phoenix Players Theatre Group (PPTG)—an inmate-led program, facilitated by volunteers from Cornell and Ithaca College, that uses acting and writing as tools of personal transformation. Each Friday, Levitt and his colleagues travel to Auburn to help the inmates develop scenes and monologues that explore their experiences. Every spring for the past four years, the group has performed those works for some eighty invited guests; this year’s show is entitled An Indeterminate Life, a nod to New York State’s policy of indeterminate sentencing.

As Levitt explains on the forty-five-minute drive to Auburn, the system is designed to reward good behavior in prison with less time served—but in practice, parole boards tend to be more influenced by an inmate’s original crime than what he’s made of his life behind bars. “What we’ve witnessed with these guys is their hunger for confronting what they’ve done, for understanding that they’re not their crime—that they’re rich, full individuals who have worth beyond their labels of incarcerated people,” Levitt tells me as we cruise north. “Being able to tell their own stories, to create a safe place for themselves in the context of an institution where things aren’t very safe, is important not only to their ability to transform themselves—to grow artistically, intellectually, emotionally, and psychologically—but also to being citizens of the world if they ever get out.”

Opened in 1817, Auburn is a maximum-security prison straight out of Hollywood—Dickensian stone walls, fences topped by razor wire, cell blocks surrounding a central yard. At the main entrance is a piece of the original gate, an antique slab of black iron that looks like it could seal a dungeon on Game of Thrones. Outside is a historical marker like those found all around New York; it notes that the world’s first execution by electric chair was held here in 1890.

Before my visit, Levitt forwards me a long list of rules for entry. Cell phones must stay in the car. You can bring in a bottle of water—and you should, because the prison is hot, dry, and stuffy—but it has to be sealed by the manufacturer. No car remotes, large sums of money, or expensive jewelry. At the visitors’ entrance, a sign also prohibits Bibles, Korans, board games, cards, keys, and children’s toys.

Then there’s the dress code, which proscribes “halter tops, leggings, jeggings, or tight-fitting clothing, mini-skirts, short-shorts, see-through clothing, plunging necklines, T-shirts containing statements or references promoting crime, drugs, alcohol, or sadistic/violent, satanic, sexual, pornographic, vulgar, or gang-related references or ethnic slurs.” During a pre-visit phone call, the Department of Corrections’ collegial director of volunteer programs has already advised me of the protocols that can be triggered when an underwire bra sets off the metal detector.

On Monday night, our group waits in the reception area for half an hour before there’s enough staff to process us, a situation that’s fairly common and often can’t be helped. “Busy day,” a friendly guard observes. “There were some bad boys.” Once we’re admitted—and have received an ultraviolet hand stamp that will allow us to leave—we’re escorted down hallways, up and down staircases, through airlock-style gates. As some corrections officers walk by, one mentions that the evening’s misdeeds included two stabbings and an assault. It brings to mind something Levitt said in the car: “I once asked one of the COs what the job was like, and he said, ‘90 percent boredom, 10 percent terror.’ There are 1,800 men incarcerated at Auburn, and a lot of them are not ready for our group or any other. So the COs’ jobs are potentially tedious, but sometimes dangerous. One thing that the PPTG guys have pointed out is that the officers are incarcerated too—they just get to go home at the end of their shift.”

PPTG member Leroy Taylor in the Auburn chapel.

After a few minutes’ walk, we’re outdoors again. As we approach the chapel—the venue for the PPTG show—we pass a block of cells. Noise erupts instantly; it’s like someone pushed a button labeled “catcalls.” Our group includes five women: myself, Van Dyke, the two undergrads, and Levitt’s wife, Judy, an acting professor at Ithaca College. It’s hard to make out much of what’s being shouted down at us, but one comment—directed at Sandra Oyeneyin ’14, who’s African American—comes through loud and clear. “Yeah, chocolate,” the voice says. “I see you.” It’s unsettling—but, as the young women note later, it’s a more low-key commute than what they experience after regular PPTG classes, when their walk back from the school building takes them through a yard filled with more than 500 men. “It’s like parting the Red Sea,” says IC junior Blaize Hall. “You walk through and feel so many pairs of eyes on you. I’ve never felt unsafe, but it’s like you’re in a fishbowl.”

When we get to the chapel, it’s a relative oasis. Yes, the wooden pews are battered and there are convex security mirrors on the walls. But if you can ignore the basketball game pounding the floor in the gym above, the atmosphere is calm. And the inmates, when they arrive, are extraordinarily warm and gracious.

There are five of them, their numbers having been reduced by recent transfers to other facilities: Molina (nicknamed “Meat”), who grew up in Elmira; Rochester native Michael Rhynes, the group’s soft-spoken co-founder and paterfamilias, who sports Buddhist prayer beads around his neck; David Bendezu, a sweet-faced twenty-seven-year-old from Yonkers, a self-described “kid from the ghetto” with a shy smile; Nate Powell, a brainy Ithaca High School alum and former Columbia undergrad with curly gray hair and a slight paunch; and Leroy Taylor, a garrulous father of four from the Albany area, who has brought photos of his kids to show the visiting reporter.

The inmates and volunteers greet each other warmly; for both groups, the class is a highlight of their week. “It has become a cliché, but the people who teach at Auburn say almost universally that these are the best students they’ve ever had,” says Levitt. “They’re so devoted to learning, so hungry for knowledge, so eager to expand their minds. For us, those rewards are enormous. But we’re also exposed to a world that we never thought we’d be part of—to different perspectives about life, society, the criminal justice system, notions of what it is to be human.”

When one conjures up stereotypes of felons serving hard time, it’s nothing like these five men—who, admittedly, needed sterling behavior records to join PPTG in the first place. The inmates themselves acknowledge that they can be much more approachable in acting class than in the prison at large, where tough-guy attitudes are the norm. “When I went to prison, I told myself I had to man up; this is a man’s prison and I was a nineteen-year-old kid,” says Bendezu, who’s so nervous about talking to a reporter that his hands shake and his voice catches. “This helps me regain my past, the youth of me. The rest of the week, I see everyone else wearing the mask that I’m wearing. Before PPTG, I didn’t know I could take it off.”

One of Bendezu’s pieces in An Indeterminate Life is entitled “Ghost Bus.” It recalls how, as a twelve-year-old out grocery shopping with his mother, he’d seen a mysterious vehicle with tinted windows. The thought of that bus haunted him over the years—until he found himself on it, looking out at his old neighborhood en route to Auburn to serve fifteen years to life. “I want people to know that PPTG is not about rehabilitation,” says Bendezu, whose first parole date is in 2021. “Rehabilitation is when you have to fix something. This lets you be free. It lets you be who you are, no matter what baggage you carry or what you’ve done in the past.”

Founded in 2009, PPTG has its roots in an ambitious plan that Michael Rhynes conceived while in Attica: to revisit the Harlem Renaissance through performing arts programs for prisoners. While that never panned out, Rhynes—who has been incarcerated since 1985 and doesn’t come up for parole until 2037—sought to develop an arts-based program at Auburn with some like-minded inmates. “They were looking for a way to take charge of their own redemption,” Levitt explains. “They had the sense that rehabilitation as it’s defined is imposed from the outside; the people being rehabilitated don’t have much say, no matter how worthy the program. They wanted to look at themselves and their behavior through a different lens.”

Call to witness: Bendezu (left) and PPTG co-founder Michael Rhynes in rehearsal.

In the Cornell Prison Education Program (CPEP)—which brings professors to Auburn to teach classes that inmates take toward an associate degree—Rhynes had studied theatre, most memorably Fences by the African American playwright August Wilson. “I got the idea that we needed an acting program for ourselves, independent of Cornell,” he says, “because they leave, and when they leave it’s like we have nothing.” Once the DOC gave its blessing, the founders contacted Cornell theatre professor Stephen Cole, since retired. “Stephen interviewed with them—in other words, the inmates were in charge of the interview,” says Levitt, who joined the group in 2010. “He met with them three times before they said, ‘OK, you can work with us.'”

Each PPTG class opens and closes with stretching, deep breathing, and a recitation of the group’s mantra: “We are a community of transformation. Through the power of self-discovery, we create the opportunity to know and grow into ourselves.” The group is self-governing; core members replenish their ranks by inviting qualified inmates to apply, a process that includes a six-page form. “This is a toxic environment in many respects, and there are limited opportunities to make a positive difference,” says Powell. “PPTG represents one way to make a contribution, and not just for the members. You can also use what you learn here to help people in the regular population who are moving in a positive direction.”

For the members, a key goal of PPTG is to be “witnessed”—that is, to be seen as human beings rather than mug shots, inmate numbers, green prison uniforms, or (as Rhynes puts it in a monologue) animals in a zoo. “They’re intent upon getting the word out that they’re useful people who have something to offer,” says Judy Levitt. “Their desire to connect with the audience is palpable, because they want people to know who they really are and to challenge the stereotypes of prison and prisoners.” The program also breaks down boundaries by having inmates share the stage with PPTG facilitators, who contribute their own material. “There’s something about witnessing that’s of utmost importance in theatre,” muses facilitator Nick Fesette; the son and grandson of corrections officers, he’s doing a PhD thesis on prison theatre. “I think that counteracts what prison tries to do, which is incarcerate people and forget them. Theatre works against prison in a dynamic way.”

While the PPTG process offers myriad insights into the inmates’ backgrounds and emotional lives, the facilitators often don’t glean what many would consider the bottom line: the precise nature of the men’s crimes. Details do trickle out; in one of Taylor’s pieces, he describes how his son found out via Google that he’d been involved in a shooting and high-speed chase. And of course, the students and professors know that just being incarcerated at Auburn means that an inmate has been convicted of a serious felony, often murder. But they delve no deeper. “I don’t want to know, because I don’t want to think of them like that,” says Hall. “That’s not who they are now. They’re these beautiful people whom I care so much about.” Adds Levitt: “We want to take them as we see them. Most of them committed their offenses anywhere from eight to thirty years ago. They’re not the people they were at that moment. You can look them up on the DOC website, because their crimes and sentences are public—but we don’t.”

Grad student Nick Fesette (left), Rhynes, and Molina performing in An Indeterminate Life.

But reporters are a different breed. When I got back from my first visit to Auburn, I spent hours online researching the men and their cases. With one exception—a crime that predated the Internet—I found out what they’d done, sometimes in graphic detail. The crimes ranged from a tragic accident to a grisly horror show out of “CSI.” But in nearly every case, reconciling those acts with the men I’d met was all but impossible. “This brings home the fact that people are multidimensional,” Levitt observes. “They’re warm, wonderful guys—and at one point in their lives, they did these things. But they’re capable of change.”

On the drive back to the prison on Friday night—Van Dyke at the wheel, the Levitts warning her of speed traps—we talk about how Auburn sticks with you, how you can’t help but think about it as you’re living your life. Van Dyke points out that visiting a maximum security prison guarantees that you’ll never take your personal liberty for granted. “I know this will sound bizarre,” she says. “But every morning when I wake up in my room, I’m aware that the men don’t have this. Not in a sentimental way; not, ‘This is so sad for them, and I’m so lucky.’ It’s just an awareness of the world in a different way.”

The professors note that although few Americans ever get a first-hand look at prison life, the corrections system is everyone’s problem. They cite the familiar national statistics: the U.S. has the world’s highest per-capita incarceration rate; some 2.4 million Americans are behind bars; since 1980, our prison population has quadrupled. While there’s hardly widespread political support for enriching the lives of felons through programs like PPTG, Levitt calls them an essential investment in human capital—if for no other reason than enlightened self-interest. “The culture has decided to warehouse people, and it’s an unnatural and bizarre system,” Levitt observes. “But 95 percent of inmates will be released. And if they’re coming to a theater near you, how do you want them to be when they get out?”

Images courtesy of PPTG