Demoliton derby: A house on Dryden Road (next to the already-vanished Palms) makes way for an MBA center.

When MaryDena Apodaca ’11 and Dan Cahalane ’12 were undergrads, they and their friends routinely held marathon hang-out sessions at Stella’s Café in Collegetown until 2 a.m. — sipping specialty drinks, playing board games, meeting old friends and making new ones. “It was our go-to place,” Cahalane says. “You were not just here to get coffee. You were here to have ideas, to get taken into interesting discussions.”

Apodaca and Cahalane met at Stella’s, soon started dating, and eventually got married. On a night in mid-July, during the final few hours before Stella’s closed for good, the couple sit together at a booth reminiscing about old times — and wondering where future generations of students would have similar experiences. “Spaces like this foster great writers, great ideas,” says Apodaca. “You can’t do that in a Starbucks or a Dunkin’ Donuts.”

Apodaca looks up from her Royal London Fog tea — a Stella’s staple — and toward the new Dunkin’ across the street, which had recently opened just a few storefronts down from a Starbucks. With its pink-and-orange sign and bright fluorescent lighting, the donut franchise offers a startling contrast to Stella’s subdued hues and indie mood. Apodaca and Cahalane note the symbolism — and say they hope it doesn’t represent the neighborhood’s future. Observes Cahalane: “You could lose what makes this place special.”

Collegetown is in the midst of a transformation, one that stands to remake its skyline. A series of important zoning changes has unleashed a wave of development — projects that city officials say will bring badly needed, and much improved, housing options to the thousands of students who live there. But what will that mean for the neighborhood’s essential character?

In with the new: A quartet of construction projects, just steps away from each other, is remaking the neighborhood.

You could forgive alumni for worrying that the Collegetown they knew and loved is disappearing. The list of beloved locations — particularly bars — that have shut their doors keeps getting longer: Johnny O’s and Dino’s (closed in 2011); the Royal Palm Tavern (2012); the Chapter House (heavily damaged in a fire last April, but slated to be rebuilt); and now Stella’s. “Every generation has its favorite local establishments, and most of them eventually close,” says Corey Earle ’07, University historian and associate director of Student and Young Alumni Programs, citing once-legendary watering holes such as Zinck’s and Johnny’s Big Red Grill. “But I think it’s fair to say that the last five years have seen the departure of more iconic Collegetown institutions in fewer years than is typical.”

Coming in their place, primarily, is a spate of dense building projects. In the radius of about one block, for instance, three six-story structures are expected to rise over the next few years: a Cornell MBA center where the Palms once stood; an adjacent student apartment house near the intersection of College Avenue and Dryden Road; and another, called Collegetown Crossing, at 307 College Avenue, near the Nines. Down the street, the John Snaith House at 140 College Avenue is getting a 3,800-square-foot, twelve-bedroom addition; another developer is asking for permission to put a six-story high-rise at 304 College Avenue, according to the Daily Sun.

And that’s just in upper Collegetown. Go a half-block west from College Avenue and you’ll find a three-story, $1.7 million apartment building moving toward completion on Catherine Street. Walk another half-block west and you’ll find two major projects rising along Eddy Street: a twelve-bedroom, $750,000 apartment building in the place of a home destroyed in a March 2014 fire; and another new apartment building (this one five stories) next to Fontana’s shoe store. These developments come in addition to a massive 1,226-unit project off of East State Street — called Collegetown Terrace, though not strictly located in the neighborhood — which cost over $70 million to build over several years. (Much of that project has been completed, but additional construction is expected into 2017.) All together, about 750 new rooms have come on the market in Collegetown between 2012 and 2015. An additional 730 are expected to be built in the three years after that, according to one recent analysis in the Ithaca Voice.

Mayor Svante Myrick ’09, a leading proponent of the zoning changes, says that the housing spurt is essential — and long overdue. Myrick, who lives on the outer edge of Collegetown, is not apathetic to the bars’ closures, but he thinks the new housing is more important than keeping vestiges of old hangouts alive. “Nostalgia is a valuable thing, and I say that as someone who worked at the Palms and lived above the Palms and spent just about every possible moment at the Palms,” he says. “But the good feeling we [alumni] get coming to Ithaca every five years and seeing the rundown institutions we once enjoyed — preserving those moments is not worth allowing students to continue living in near squalor.”

Myrick, city officials, and local developers say that Collegetown is on the verge of transforming its housing stock for the first time since a wave of high-rises first appeared on Dryden Road in the Nineties. As Myrick notes, basic laws of supply and demand have hurt students’ ability to secure or demand quality housing. In 2007, the City of Ithaca put a moratorium on new building development in Collegetown. Overall, from 2005 to 2014, Cornell increased its enrollment by about 2,400 undergrads and grad students while only 657 new housing units were added in the city, according to Myrick.

He notes that there’s ample evidence that the situation gave landlords the upper hand. In 2014, the New York Times put Ithaca at number eleven on its list of the least affordable cities in the United States, right behind New York City. (Rents for some studio apartments in Collegetown run above $1,200, according to the website of one major landlord — rivaling rates in Boston and San Francisco.) A few years ago, crowds of students started sleeping outside the Ithaca Renting Company office in advance of the day that leases for the following year became available, setting up camp as early as 5 p.m. the night before to land a coveted property. In October 2014, as many as forty groups of hopeful housemates showed up. As Rohit Jha ’17 told the Daily Sun at the time: “I was nervous that the order would break down and I would not be left a place to live for next year.”

Coffee wars: Until Stella’s closed (shortly after Dunkin’ Donuts opened), there were briefly four places to grab some caffeine on the same stretch of College Avenue. Three remain: Dunkin’, the locally owned Collegetown Bagels, and Starbucks.

The surge in Collegetown housing demand has not just driven rents up. It has also changed the neighborhood’s demographics by forcing many families out, since properties tend to be priced as though each resident is paying for his or her own bedroom. Tom Hanna ’64, a retired Human Ecology staffer who grew up in Collegetown in the Forties and still lives in Ithaca, saw that transformation firsthand. “The long-term trend is for single-family homes to be converted, one by one, into student housing,” he says. “When I was a kid, we had plenty of families in Collegetown — growing families, with kids. You don’t see that very much anymore.” With students increasingly comprising the pool of tenants, housing conditions deteriorated; Myrick says he has gotten numerous e-mails from parents who are dismayed that their children are living in homes with mold and broken ceilings. In 2014, a landlord was fined for housing eight students in a property where only three were allowed.

Could the new construction make the balance of power tilt toward equilibrium, so renters aren’t at such a disadvantage? Myrick is optimistic. “I think the students ten years from now will be tremendously lucky,” he says. “The quality of housing they’ll live in will be safer and cleaner — and, adjusted for inflation, I believe it will be cheaper.” Josh Lower ’05, an Ithaca native and developer whose father was a Collegetown landlord, is also bullish about the neighborhood’s future. Lower’s construction crews broke ground in July on the six-story building at 307 College Avenue that will house a ground-level GreenStar food market — the first grocery store in Collegetown in decades — as well as a new laundromat and a transit hub for TCAT buses. “We’re going to get more housing options, more services, and more commercial stores,” Lower says — noting that on the flip side, rising real estate values might make it harder for stores that aren’t particularly profitable to hang on. Like Myrick, Lower sees the recent changes in Collegetown as ushering in an era of much better quality housing for students — and sees the drop-off in bar business as an inevitable casualty of the higher drinking age. “The bar scene used to be more lively because 75 to 80 percent of the people who wanted to go to the bar could drink,” he says. “Now it’s flipped: 75 to 80 percent of students aren’t old enough to go to the bars.”

Neither has Collegetown been immune to national trends in retailing. Lower points toamazon.com and other online and tech-driven options that make it increasingly difficult for brick-and-mortar stores to turn a profit. Collegetown Video, for instance, closed in 2010 — just as Netflix began to boom — and the neighborhood no longer has stores devoted to books or music, niches now largely filled online. “Everybody has smartphones,” Lower says, “so for a lot of commercial tenants it’s really difficult to find something that can make it.”

But while some traditional bar and retail options have closed, today’s Collegetown has also found life in new sectors, like tech. One of the most visible recent additions is PopShop, a student-run co-working space near the intersection of College and Dryden geared toward aspiring entrepreneurs. Opened in 2012, PopShop hosts events that routinely draw crowds of hundreds looking to join or found a new company; most nights, the glow of laptops can be seen from across the street, lighting up the storefront late into the evening. As Cornell moves forward with its new tech campus in New York City, it’s also expanding its entrepreneurial efforts locally, with a two-floor, 10,000-square-foot location at 409 College Avenue planned for eHub, a business incubator that will also cater to student-run companies, including Student Agencies. “You need to build a space right in the middle of the start-up community,” says Zachary Shulman ’87, JD ’90, director of Entrepreneurship at Cornell. “And for the students, that community is in Collegetown.”

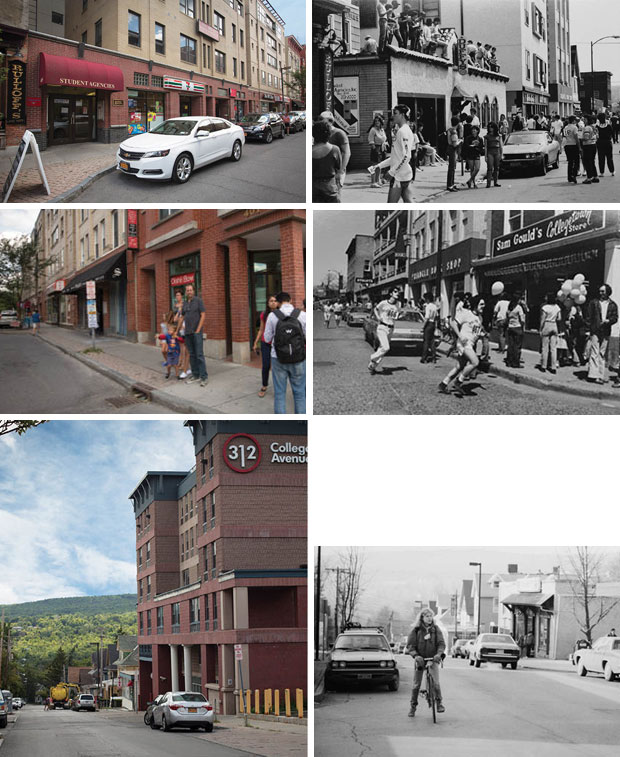

Then and now: Photos from the Seventies and Eighties (including snapshots of a road race through Collegetown) offer a contrast to how those same locations look today.

The MBA building on the former Palms site — projected to cost $12 million and open in 2017 — could also help expand the neighborhood’s appeal. Soumitra Dutta, dean of the Johnson School, says the “state-of-the-art, modern facility” will fit with the city’s vision of a Collegetown that appeals to faculty, staff, students, and alumni. By holding classes year-round, Dutta says, the MBA project “will generate significant foot traffic and economic activity for other Collegetown businesses.” And that could have a long-term impact on the character of the neighborhood, says Ithaca alderman Graham Kerslick, who represents Collegetown. “I think that’s better for the community if it’s not just empty during the breaks,” says Kerslick, executive director of Cornell’s Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future. “It will be more of a year-round community.”

Such changes could bring Collegetown full-circle — back to being a neighborhood where families, young professionals, and undergraduates all cross paths. “Collegetown today is primarily about off-campus housing for Cornell students,” says Tom Schryver ’93, MBA ’02, executive director of the Center for Regional Advancement at Cornell. “But it’s turning into a lot more than that: the University will be building a presence of people working there every day that will yield new opportunities.”

Does that mean alumni should fear that they’ll find Collegetown unrecognizable when they return for Homecoming? Myrick argues that, like it or not, change has always been part of the neighborhood’s essential character. “I’d be tempted to say, ‘This isn’t your father’s Collegetown,'” he says. “But it’s not even your upperclassman’s Collegetown. The truth is, no two classes at Cornell have had the same Collegetown experience.”

Photos: Jason Koski / UP

Those Were the Days

A roundup of late, lamented Collegetown Haunts

Café Decadence This dessert shop featured such delectables as the Ultimate Cookie — layers of sugar cookies, chocolate cheesecake, and chocolate truffle. Located on Dryden Road, it was a favorite spot for dates and indulgences.  The Chapter House When this Lower Collegetown stalwart was destroyed in a fire last spring, Ithacans lost an institution where people of all stripes gathered to have beer and popcorn, play games, and listen to live music. The owners announced over the summer that they intend to rebuild, so this well-loved establishment will start its next chapter in 2016. The Chariot This Eddy Street restaurant, which closed in 2005, is remembered most fondly for its deep-dish pizza and unusual basement location. Its warm atmosphere set the tone for “Monday Night Football” and casual dinners, where patrons would choose from a long beer menu, snack on corn nuggets and jalapeño poppers, and indulge in the only dessert offered: cheesecake. The Connection Not to be confused with the pizza place on Stewart Avenue that until recently bore the same name, this bar was next to the Nines on College Avenue. A dark, quiet joint that saw its prime in the Eighties, it was beloved for its free popcorn and a juke box playing such classics as “Puff the Magic Dragon.”

The Chapter House When this Lower Collegetown stalwart was destroyed in a fire last spring, Ithacans lost an institution where people of all stripes gathered to have beer and popcorn, play games, and listen to live music. The owners announced over the summer that they intend to rebuild, so this well-loved establishment will start its next chapter in 2016. The Chariot This Eddy Street restaurant, which closed in 2005, is remembered most fondly for its deep-dish pizza and unusual basement location. Its warm atmosphere set the tone for “Monday Night Football” and casual dinners, where patrons would choose from a long beer menu, snack on corn nuggets and jalapeño poppers, and indulge in the only dessert offered: cheesecake. The Connection Not to be confused with the pizza place on Stewart Avenue that until recently bore the same name, this bar was next to the Nines on College Avenue. A dark, quiet joint that saw its prime in the Eighties, it was beloved for its free popcorn and a juke box playing such classics as “Puff the Magic Dragon.”  Dino’s Unlike many of the bars that closed due to shifting trends in student drinking habits, Dino’s shut down in 2011 because the building’s owner didn’t renew its lease. It was a favorite destination for students over the previous three decades, with trivia nights, ladies’ night specials, classic bar food, and a dance floor in back.

Dino’s Unlike many of the bars that closed due to shifting trends in student drinking habits, Dino’s shut down in 2011 because the building’s owner didn’t renew its lease. It was a favorite destination for students over the previous three decades, with trivia nights, ladies’ night specials, classic bar food, and a dance floor in back.  Johnny O’s While its sister establishment, the Ale House, still operates downtown on Restaurant Row, this bar closed in 2011. Popular among the Greek crowd, it hosted weekend dance parties with a D.J.

Johnny O’s While its sister establishment, the Ale House, still operates downtown on Restaurant Row, this bar closed in 2011. Popular among the Greek crowd, it hosted weekend dance parties with a D.J.  Johnny’s Big Red Grill Even decades after their time on the Hill, alumni still remember the iconic sign that hung over this restaurant. (It was taken down in 2009, almost thirty years after the establishment closed, and is now housed in a sign museum in Ohio.) Students crowded the bar and restaurant — where, as late as the Seventies, you could get a meal for $1.50. The son of the Grill’s owners launched another Cornellian institution: the Hot Truck. Pop’s Place This Collegetown hangout opened as an ice cream parlor in the Twenties, and expanded into a full-blown restaurant in the Fifties. Cornellians of a certain era may recall a distinctive musical feature: it had an automated violin, akin to a player piano. Located in the storefront that now houses Collegetown Bagels, it remained in business until the mid-Seventies.

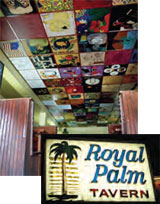

Johnny’s Big Red Grill Even decades after their time on the Hill, alumni still remember the iconic sign that hung over this restaurant. (It was taken down in 2009, almost thirty years after the establishment closed, and is now housed in a sign museum in Ohio.) Students crowded the bar and restaurant — where, as late as the Seventies, you could get a meal for $1.50. The son of the Grill’s owners launched another Cornellian institution: the Hot Truck. Pop’s Place This Collegetown hangout opened as an ice cream parlor in the Twenties, and expanded into a full-blown restaurant in the Fifties. Cornellians of a certain era may recall a distinctive musical feature: it had an automated violin, akin to a player piano. Located in the storefront that now houses Collegetown Bagels, it remained in business until the mid-Seventies.  The Royal Palm Tavern Owners, employees, and patrons alike affectionately embraced the dive-bar reputation that the Palms earned over its seventy-one years in business. Fans came to expect sticky surfaces, a limited drink menu, and graffiti on the tables and walls. By the time the bar closed in 2012, nearly every ceiling tile had been painted and nearly every surface danced on. Stella’s Opened in the early Nineties and closed just months ago, Stella’s offered a classy alternative to Collegetown’s many casual options. The rotating menu featured local, organic, and sustainable ingredients and a long cocktail list; its adjacent café offered finely made coffee drinks and pastries. “It was always such a reprieve from other bars where people were looking to rage,” says former regular Dan Kuhr ’13. “It’s still the bar by which I measure other cocktail establishments.” The University Delicatessen Nicknamed Uni Deli, this sandwich shop was in the heart of Collegetown, at the corner of Dryden Road and College Avenue. Students flocked there in the Seventies for reasonably priced subs and milkshakes.

The Royal Palm Tavern Owners, employees, and patrons alike affectionately embraced the dive-bar reputation that the Palms earned over its seventy-one years in business. Fans came to expect sticky surfaces, a limited drink menu, and graffiti on the tables and walls. By the time the bar closed in 2012, nearly every ceiling tile had been painted and nearly every surface danced on. Stella’s Opened in the early Nineties and closed just months ago, Stella’s offered a classy alternative to Collegetown’s many casual options. The rotating menu featured local, organic, and sustainable ingredients and a long cocktail list; its adjacent café offered finely made coffee drinks and pastries. “It was always such a reprieve from other bars where people were looking to rage,” says former regular Dan Kuhr ’13. “It’s still the bar by which I measure other cocktail establishments.” The University Delicatessen Nicknamed Uni Deli, this sandwich shop was in the heart of Collegetown, at the corner of Dryden Road and College Avenue. Students flocked there in the Seventies for reasonably priced subs and milkshakes.

Have any of your favorite Collegetown spots vanished? Leave your memories in the comments, and post photos in our new online gallery at cornellalumnimagazine.com/photogallery.