Provided

The new memoir by Meredith Talusan, MA ’11, MFA ’15, focuses on the author’s first two and a half decades; except for a brief coda, it ends with her decision to undergo gender confirmation surgery in 2002, when she was in her mid-twenties. But in those 320 pages, Talusan recounts such a breadth and depth of experiences, they’re enough to fill several lifetimes.

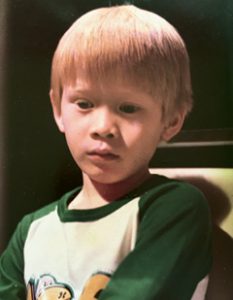

As an albino in her native Philippines, Talusan’s blond hair and light skin were an advantage in a society where whiteness was prized, though she struggled with the poor eyesight common to people with the condition. Assigned male at birth, she became a well-known child actor, portraying the star’s precocious son on a popular TV sitcom. Her family life was fraught, her childhood marked by abuse and neglect: her mother was an addicted gambler and her father an alcoholic, and she found refuge in the care of a beloved grandmother. As a teenager she emigrated to the U.S. with her family and later won a scholarship to Harvard—where she was an out gay man who became the talk of campus with a wildly popular, sexually explicit one-person show dubbed Dancing Deviant.

Talusan as a young boy in the Philippines, an image she has shared online when writing about her childhood.Provided

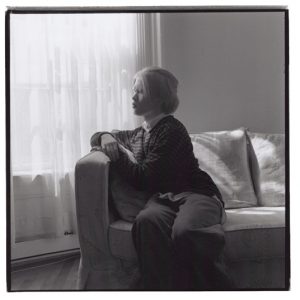

After graduating in 1997 Talusan worked in an MIT cognitive science lab and pursued art photography, creating self-portraits in which she explored her femininity. While living as a man in Boston, she was in a committed relationship with Ralph Wedgwood, PhD ’94, a philosophy professor from an aristocratic British family (he has since inherited the title of baronet). As Talusan felt drawn to express herself as female, her embrace of makeup and women’s clothing caused friction between them, and her decision to transition ultimately meant the end of their romance. “I didn’t really challenge Ralph’s refusal to accept me as his lover when I presented myself as a woman,” she writes. “I couldn’t picture myself as a woman with him either, my twin spirit unable to perceive him as the person my male self held so dear.”

Talusan’s memoir is called Fairest, a title that operates on multiple levels: it touches on the privilege accorded by her light skin, on issues of social justice for LGBTQ people, and on perceptions of her own physical attractiveness, both as a man and a woman. As she writes, while her fit, youthful body gave her currency and power as a gay man, it wasn’t until she began living as a woman that she was widely perceived as conventionally good looking—and that attention was sometimes intoxicating. “Certainly, I didn’t always feel that the woman’s voice inside of me was benevolent,” she writes. “Released after a lifetime of hibernation, she could be selfish and rapacious, able to justify any action through the sheer enormity of her desires. I often felt as if I was in a trance, heeding no call except that beguiling woman who stared at me from the other side of the mirror whenever I put on makeup, my transformation something out of alchemy, the stuff of myth. Maybe she was a siren, yet I was afraid to think of her that way because I knew that sirens led seafarers astray.”

Talusan, who trained as a photographer, in a self-portrait.Provided

Just as Talusan’s albinism led strangers to assume she was white, her slender frame made it easy for her to “pass” as a cisgender woman—parallel truths that she contemplates throughout Fairest. “I wanted to write a memoir that deals with my gender identity, but through the lens of racial perception,” Talusan says, speaking with CAM via videoconference in July. “Even though I’ve led so many different lives and have gone through so many different transitions, that became a guiding principal for the book.” Among Talusan’s distinct perspectives is the fact that she spent years as an out, proud gay man before transitioning, and never felt she had a dysphoric relationship with her male body. Although citing the name that a trans person was given at birth is generally considered offensive and demeaning—so much so that there’s a well-known term for it, “deadnaming”—Talusan is comfortable reporting her own when it’s relevant, and some of her online essays relating to her childhood have been accompanied by photos of her as a towheaded little boy.

But for years—including when she first got to Cornell, where she earned both a master’s in comparative literature and an MFA in fiction writing—Talusan wasn’t widely out as trans. It’s a period she doesn’t cover extensively in her memoir, which essentially concludes with her decision to travel to Thailand for gender confirmation surgery nearly two decades ago, after which she moved to California to pursue an MFA in visual arts. As she observes in a recent online essay tied to the book’s release, several years after her surgery she found herself leaning in to the ease and safety of having people assume she’d been assigned female at birth; when she moved to New York City in the mid-Aughts and later to Ithaca, she decided to “go stealth” and not generally disclose she was trans. “The image that comes to mind when I think of that period from fall 2006 to spring 2014 is of a snow globe, maybe in part because it snows in Ithaca eight months out of the year,” she writes. “I was aware that the reality I’d constructed for myself—of being an ordinary, cisgender woman in grad school—was in the end just an illusion, but that didn’t matter as long as I stayed within the confines of that globe, as long as the actual, painful reality around that artificial utopia didn’t intrude. And with the benefit of hindsight, I’ve come to accept that this was exactly what I wanted for a while, to be encased in glass so that a world that was unkind and violent toward trans people couldn’t destroy me.”

Talusan (right) and her husband, Josh, on their wedding day. The ceremony was held at an artists’ colony in New York’s Catskill Mountains.Rhys Harper

Talusan eventually came out as trans at Cornell, and her emergence as an activist and journalist followed an episode in which, she says, she was the victim of harassment and other hostile behavior by fellow residents of Telluride House, a self-governing residence where she had a room-and-board scholarship that helped her get through grad school. She lodged a complaint, the situation escalated, and after a loud argument at the dinner table, Talusan herself faced formal accusations of bullying. The house broke into factions over the dispute, and, she says, at one point during the months-long conflict, some house members tried unsuccessfully to get Ithaca police to forcibly remove her. The story was covered in national media including Salon and the Advocate, and a Change.org petition decrying what Talusan called an illegal eviction garnered nearly 1,700 signatures.

It all came to a head as Talusan was leaving for the Philippines to cover a story for BuzzFeed News about a transwoman murdered by a U.S. Marine. Ultimately, Talusan moved out, decamping to an apartment for her final semester at Cornell and deciding to pursue reporting and essay writing full time rather than stay for a PhD. “It was the first time being trans had significant, long-term consequences for my life, and it motivated my journalism career,” Talusan, who’s now at work on a novel, says of the Telluride episode. “Feeling powerless to advocate for myself propelled my desire to advocate for other people.”

Talusan has since published in the New York Times, the Guardian, the Atlantic, WIRED, the Nation, and more. She’s the founding executive editor at Them, Condé Nast’s online platform for the LGBTQ community; in 2017 she won a GLAAD Media Award for outstanding digital journalism for Unerased: Counting Transgender Lives, a documentary on violence against trans people that’s viewable on Mic, a millennial-focused media site. “Meredith is always striving for some sort of understanding, first for herself and then so she can translate that understanding to her readership,” says Helena María Viramontes, one of Talusan’s professors in Cornell’s famously selective MFA program in fiction writing, which accepts only four students per year out of some 700 applicants. “I’ve always respected her for that.”

Since Fairest came out in May, it’s been widely covered in the national media, including NPR, Slate, and InStyle. “The phenomenon of passing is complicated, and rightly thorny,” a New York Times critic observed. “Of course no one should have to hide her transness, or her Asianness, to be safe on a dark street, or to achieve her personal or professional goals. And yet her darker-skinned brother experiences life in a harsher America. Talusan navigates these complex dynamics graciously, acknowledging both her privileges and their cost: the constant threat of being exposed as herself.” Said Publishers Weekly in a starred review: “This elegant memoir examining whiteness, womanhood, and the shaping of identity will resonate with readers of any community, LGBTQ or not.”

As an essayist, Talusan has contemplated such topics as transphobia in Hollywood comedies, the dating challenges faced by gender nonconforming people, the role that wearing—or not wearing—makeup has played in her feminine identity, and what it’s like to be both trans and an immigrant during the Trump Administration. In a BuzzFeed piece headlined “What I Learned From My Neuroatypical Partner,” she pondered her relationship with her then-boyfriend (now husband), Josh, who has ADD and is on the autism spectrum. “Having lived most of my life inordinately concerned with how other people see me, being with Josh allows me to understand that what matters is not other people’s perceptions, but the reality I actually experience with him,” she writes. “In this image-driven, media-saturated world, which Josh pays little attention to, he constantly reminds me that it’s more important for us to be happy than to look happy, for us to feel attractive to ourselves than for other people to perceive us as attractive, for us not to conform to society’s prescribed expectations of who to be and how to act.”

‘Lady Wedgwood’

In an excerpt from Fairest, the thought of marrying her partner prompts Talusan—then still living as a gay man—to consider whether her true path lies in transitioning to female

Talusan is visiting her childhood home in the Philippines in December 1999 when she thinks back on a train ride across Boston’s Charles River she took while commuting to work at MIT the previous fall. “I was unusually happy on that particular ride,” she writes. “At twenty-three, I had found the love of my life, my soul mate . . . I asked myself how I could possibly be any happier, when a voice inside of me said: You might be happier as a woman.” She also reflects on her day-to-day life with that partner, Ralph (pronounced “Rafe”), a wealthy older man she lives with in Boston’s Back Bay.

Talusan is visiting her childhood home in the Philippines in December 1999 when she thinks back on a train ride across Boston’s Charles River she took while commuting to work at MIT the previous fall. “I was unusually happy on that particular ride,” she writes. “At twenty-three, I had found the love of my life, my soul mate . . . I asked myself how I could possibly be any happier, when a voice inside of me said: You might be happier as a woman.” She also reflects on her day-to-day life with that partner, Ralph (pronounced “Rafe”), a wealthy older man she lives with in Boston’s Back Bay.

I got so used to that lifestyle—condo ownership, dinner parties, frequent trips to Europe—that I didn’t even notice how I slotted into a particular kind of existence, a settled gay coupledom that Ralph sought, and it felt so right being with him that for several years, it didn’t occur to me to ask whether that was what I wanted. Sitting on the train on that mundane fall day, I dismissed the idea of my womanhood as a passing notion too, an absurd thing to want in the midst of my intense happiness, compared to the havoc it would wreak if I even entertained the idea of transition, a word whose meaning I didn’t really have a frame of reference for, never having met an openly trans woman in person. I ejected it from my mind, only for the quotidian memory to be excavated in my teenage bedroom halfway around the world, after my mind once again wandered toward the territory of hesitation, why I still found it hard to see the man I thought of as my soul mate being part of this world I grew up in.

Then another memory, the summer before that train ride, having lunch al fresco in a swanky restaurant in London’s Soho district with a lesbian barrister friend of Ralph’s named Karen. She wore a brown tweed suit jacket and had close-cropped blond hair set against a symmetrical face, which made her look altogether handsome and distinguished, but in a softer way than had she been a man.

She and Ralph knew each other through their work advocating for gay marriage, as they exchanged information about the issue between America and England. I was used to this, absorbing conversation as Ralph talked to various older, learned friends, whether about arcane issues in philosophy or matters of queer-related public policy. Though I wasn’t paying that much attention—the details of lobbying the House of Lords weren’t particularly interesting to me, and I had more reservations about gay marriage than Ralph, or presumably his friend. I believed in lasting unions, even believed that Ralph and I should be married if the option were available, but I was also concerned about how marriage could compromise the countercultural force of queer life. Though this wasn’t an opinion I felt like expressing in front of a human rights lawyer and my partner, who had lectured and published on the topic.

“You know why I’m fighting for gay marriage in England?” Karen asked as she turned to me. “So you can someday be Lady Wedgwood.”

It wasn’t the first time I’d heard this; our art historian friend Tom, who followed British aristocracy, had made the same joke a couple of times to embarrass Ralph, who was self-conscious about being next in line for the title of baronet once his father died. He was to be called Sir Ralph Wedgwood according to his future position in British society as one rung above a knight, a detail he omitted about himself until after we’d been living together for six months. As a left-leaning liberal ethicist, Ralph found the idea of inheriting titles distasteful, so I tried not to get too worked up about the baronet thing myself, even though I’d been schooled in British literature and found it exciting to be partnered with a man some minor Austen character would want to marry for his title.

But this specific conversation affected me somehow, even for just the few minutes between when Karen made her comment and the rest of lunch. Vivid scenes flooded my mind, a mosaic of beautiful white women, from Gwyneth Paltrow’s blond and vivacious Emma to the gender-shifting Viola in Twelfth Night. Of course, my mind dwelled on Orlando from Virginia Woolf’s novel of the same name, a nobleman who wakes up one day and discovers that he has become a woman, and from that point on is known as Lady Orlando. Even though it was just a joke, how women who are married to baronets get the title of Lady, and so a man who marries a baronet should be called Lady too, my mind led me to the possibility of literally transforming into a woman.

I didn’t actively dislike being a man. It was more that for so much of my life, I lived vicariously through women, who were always the central characters in my favorite stories, searching for and finally finding the love of men. It was thrilling to imagine myself living these fantasies, whether in rom-coms or Shakespeare, but especially from great novels set in England. But whenever I finished those books, I had to live with the disappointment that while women in real life had the chance to experience some version of these stories, my pleasure in them was always destined to be indirect, so that one moment when a virtual stranger called me a Lady gave me an outsized amount of joy.

From FAIREST by Meredith Talusan, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2020 by Meredith Talusan.