With commissions from the New Yorker, an exhibit at the New York Public Library, and a coveted spot in a hot summer show in France, photographer Ethan Levitas '93 is about to see his career get 'launched out of a cannon'

With commissions from the New Yorker, an exhibit at the New York Public Library, and a coveted spot in a hot summer show in France, photographer Ethan Levitas '93 is about to see his career get 'launched out of a cannon'

With commissions from the New Yorker, an exhibit at the New York Public Library, and a coveted spot in a hot summer show in France, photographer Ethan Levitas '93 is about to see his career get 'launched out of a cannon'

By Beth Saulnier

Tennessee does not fall in a direct line from New York to Washington State. But in the summer of 1996, planning a cross-country trip to attend a friend's wedding, Ethan Levitas '93 felt drawn there. After nearly three years as a freelance assistant to some fifty commercial photographers, he needed to make his own work. So Levitas built a portable studio from fabric and a metal frame, "something that I could put up and break down like a circus tent." He'd seen news reports of a spate of church burnings in Tennessee, and he headed south with no clear picture of what would come next. "I was uncredentialed," he says. "I wasn't with a paper. I was just an artist trying to understand what happened."

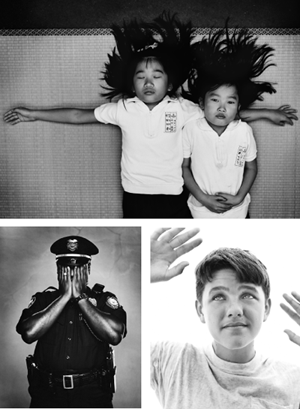

He pitched his studio in a field next to a newly rebuilt Baptist church; somehow, he got people to sit for him. Then he drove to Arkansas to photograph policemen. "Who knows what the heck I was thinking back then?" he wonders with a laugh. "These things came up in my mind as I was driving. I would imagine, Who could I juxtapose with this?" He went on to photograph shoppers at a flea market in rural Oklahoma; bikers in South Dakota; Native Americans in Montana. "It was really special to me, meeting people through the lens, working almost in silence making portraits," he recalls. "That's when I realized that portraiture was going to be the thing. It wasn't going to be about documentation, facts, or proof. It wasn't going to be about a narrative per se. It was going to be me interacting with people, somewhere between prose and poetry, between description and metaphor."

The result was Relatively Free, his first major project, which was shown in 1998 at the University of Connecticut and the Tempe Center for the Arts in Arizona. Levitas's career has been on the rise ever since, but now he's poised to break into the upper echelons of his art. The New York Public Library is currently exhibiting twenty-one of his photographs; his work is being purchased for collections both public and private; his commissioned portraits have been showing up in the New Yorker with increasing frequency; and in July, he's off to France as a nominee for the Discovery Prize at Les Rencontres D'Arles, one of the world's most prestigious photography exhibitions. "It's an exciting moment," Levitas says, under-statedly—before allowing that the Arles show could amount to having his career "launched out of a cannon."

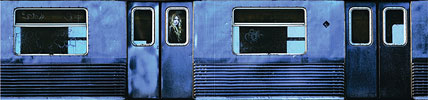

Now thirty-seven, Levitas lives and works in a 1,000-square-foot apartment in a former garment factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. The high-ceilinged space is essentially one room plus a bathroom, but Levitas has put his stamp on the place so it feels as if there are multiple zones: he has an office and a bedroom in a loft over the kitchen, and a raised platform in the middle of the main room provides storage underneath and a living room grouping above. Various tools of his trade cover a counter along one wall, and at the far end of the apartment—beneath a huge window whose heavy curtain conceals the elevated JMZ train running just outside—is a studio space dominated by two photos of subway cars, each roughly three feet by six. Lately, the trains (the project is called Untitled/This is just to say) have become Levitas's most visible work; in addition to being exhibited at the library as part of its Eminent Domain show, they've been featured in the New Yorker and the New York Times, as well as in a documentary on public television's "SundayArts" program.

Shooting at various locations, at different times of day, and in all kinds of weather, Levitas has crafted a series of portraits within portraits. Each photograph depicts one elevated train car whose windows form mini-portraits of riders that reflect the tapestry of the city, from Hassidic Jews to transit workers to canoodling teens. The trains themselves emerge as characters—covered in snow, etched with graffiti, emblazoned with American flags. "Ethan's project has altered my awareness of the subway," says Stephen Pinson, the library's curator of photography. "By subverting our expectations of perspective and scale, the trains become microcosms of the city, collapsing the distinction between our public and private selves."

Although the project began in 2004, it had its inspiration a decade earlier, when Levitas was on his way home after a year of teaching English in Japan. He flew into JFK and craved a slow route back to the city, so he took the subway. "The train was so telling, strikingly different from in Japan," he says. "It seemed to offer a metaphor, an explanation, an interesting comparison to what I had just experienced. In Tokyo the trains were immaculate and fast, but this was so rundown and dangerous and decrepit. The train was a sign of the health and wealth of the place. It embodied a lot of what we were about at that time. It was an example of the public square."

Levitas is sitting on his couch, drinking strong coffee and eating bits of a cheese-and-guava pastry he picked up in the neighborhood to welcome a guest; he keeps coughing, though he's not sick. ("It's like I'm allergic to talking about my work," he says, sounding as if he's only half kidding.) With his spiky hair, piercing eyes, scruffy goatee, and an air that's as casual as it is intense, Levitas looks every inch the artist; you'd never guess what he used to be, which is an Ivy League football star.

The son of a nurse and a sales executive, Levitas was born in Upper Manhattan and raised in suburban Middletown, New York. He majored in government on the Hill and played varsity football, starting at cornerback his junior and senior years and being named All Ivy. "Athletics were a big part of my life," says Levitas, who was a competitive swimmer as a child. "Not the culture of them, the movement of them. People don't know how to put their head around that—to be an athlete and an artist, it doesn't make sense." But for Levitas, there's a connection; he can't elucidate it completely, but he knows that the intensity of sports training relates to the extreme focus he now gives his work. "A lot of my process is about seeing how things could be, how it should be visually," he says. "I work in my head a lot, imagining the photographs that would someday be. And that part of my imagination, through some weird way, was exercised in all the training."

Levitas graduated without any clear direction; an abortive attempt to take the LSATs had made it abundantly clear he wasn't going into law. ("I had a bit of a freakout," he says. "I couldn't finish. I just put my pencil down and stopped.") He entered the Japan Exchange and Teaching program, which placed him as an English teacher in a middle school in Nagano, a mid-sized city in the mountains that would host the 1998 Winter Olympics. He became fluent in the language, and took up photography out of a desire to show people back home what he was seeing. "It was so beautiful," he says, "like if you took Colorado and put it two hours from New York." The experience of being in an unfamiliar culture, trying to make sense of it and translate it for others, he says, "was the start of being an artist."

Back in New York, he started freelancing as a photographer's assistant. After three years of seven-day weeks, he went on the cross-country trip that spawned Relatively Free, then took a full-time job as an assistant to famed photographer Ruven Afanador. He eventually returned to Japan to do an educational project for high school students, using his portraits of Americans of varying ethnic groups to spur discussions about identity— a word for which, he notes, there is no equivalent in Japanese. Called Conversation Continued, the materials were published as an English-language textbook that's still used in schools.

Since 2006, Levitas has been a regular contributor to the New Yorker, photographing such subjects as the band Animal Collective (he perched them in a hedge alongside a man in a lizard suit) and the avant-garde chef Grant Achatz (captured immolating a slab of cinnamon with a blowtorch). "The pictures are wonderful to look at, but of course that's not enough," says Elisabeth Biondi, the magazine's visuals editor, who nominated Levitas for the Arles prize. "He's very intelligent, and the New Yorker looks for intelligent photographs in its editorial pictures. They're content-oriented, and so is Ethan. He spends a lot of time getting background information and puts it all together, and out come these quite stunning photographs. They serve the function of saying something about the piece, and they sort of lift off the page."

Levitas uses a variety of equipment and techniques, deciding what each project merits—from the latest digital system to an old-fashioned barrel lens that looks like something out of the Old West. When he talks about his work—a conversation punctuated with concern that the listener must be bored silly—he never uses the phrase "take photographs"; it's always "make photographs." "It goes back to a very elemental thing, about the crazy, wide-open nature of photography itself," he says. "Most people consider the camera as just an instrument. It's a recording device you turn on or off. But other people like myself consider it a process of creation and dissemination. It's more like painting or sculpture. It's a work. There's an inspiration, a conception—a process you go through that births an unexpected moment."