Dennis was born in Ithaca, the child of Cornellians who'd stayed on the Hill for graduate studies. (His mother, Minfong Ho '73, MFA '82, is a writer who was born in Singapore; his father, John Dennis '72, PhD '87, is a consultant in international development.) His father's career took the family abroad—two years in Laos, another two in Switzerland—and there were extended visits to his mother's home country. The family settled in Ithaca for good when Dennis was thirteen—the same year his father bought him his first camera—and he graduated from Ithaca High School before matriculating in CALS, where he majored in applied economics and management. "I was always interested in photography, but it was more of a hobby," says Dennis. "Then I got involved in some political activist groups on campus, and my images started reflecting my interests. I took a class in documentary photography, and I vividly remember the first time I opened a book called Inferno by [eminent war photographer] James Nachtwey. The images just seared into my mind."

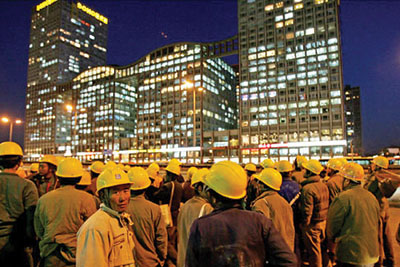

In addition to his post-graduation work in Beijing—where, among other things, he explored China's rapid urbanization—Dennis has chronicled famine in Ethiopia, post-election unrest in Kenya, xenophobic violence in South Africa, and the treatment of detainees in Iraq. He has also shot more quotidian images of life in Afghanistan and landscapes from around the world. But his war photography has gained the most notice—inspiring him to ponder the nature of such imagery and how viewers respond to it. "There's this representation of war that is romantic, glorified, and deeply ingrained in our society," says Dennis. "When I went to war for the first time as a young man, I was making images to match that version. I soon realized what I had was much more brutal, much darker—and yet photo editors wouldn't

publish them. That representation of war was inappropriate

for consumption."

Acceptable images, he says, include "a silhouette of a soldier walking with the sun behind him, or a round being dropped into a mortar tube in a cloud of dust." And an example of something deemed unpalatable? "In Baqubah, Iraq, an American patrol walked into a village and there was a decapitated head sitting on a market table with a note saying, 'This is what happens if you work with the Americans,' " Dennis says. "The American soldiers took the head and posed with it; these were young kids, and they didn't know how to respond to it except in a coy, playful way. So I had these images of Americans playing with a decapitated head. Newsweek had the opportunity to publish them, and they passed; they said it was too incendiary. But these are the types of images that represent the absurdity, the brutality of war. It's real; it happens. But we don't see them."

It was frustration with such constraints, Dennis says, that inspired him to make the leap into filmmaking. Now, he's focusing on a start-up he founded to market the technology he developed for Hell and Back Again and has no set plans to return to war. As for the images from Baqubah—they can be viewed on his website, danfungdennis.com. And ultimately, he notes, they did get published: Rolling Stone ran them in a double-page spread.

{vimeo}28912003{/vimeo}

Hell and Back Again Trailer (2:01)