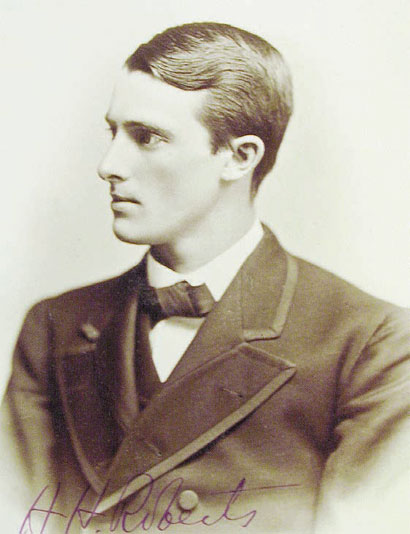

Reading Carol Kammen’s excellent article on the Morrill Land Grant Act and the founding of Cornell University got me thinking about my paternal grandfather. Henry Hurd Roberts, Class of 1875, was the son of a farmer in Rock Stream, New York, a village on the west side of Seneca Lake. We don’t know how Henry learned about the opening of Cornell, but it must have been exciting news to many young people in Upstate New York. It didn’t take him long to apply for admission to the nearby institution that aspired to be “a university of the first magnitude,” as Ezra Cornell put it.

When Henry arrived on campus in 1871, there was little here except for the “Stone Row”—the buildings that would become Morrill, White, and McGraw halls—and a collection of ramshackle sheds and houses. (One was “a flimsy structure built by energetic students for their own lodging,” reported Morris Bishop 1913, PhD ’26, in his History of Cornell. Its occupants included David Starr Jordan 1872, who would go on to become the first president of Stanford University.)

The faculty was small—thirty-seven men, counting President Andrew Dickson White, who also served as a professor of history. Most of them were young. The living quarters for both faculty and students were rudimentary, the food was questionable, and the sanitary conditions were bad. Fire and disease were constant threats. Ezra Cornell roamed the campus, supervising the construction of buildings and casting a critical eye on anything that didn’t suit his practical instincts. He was, as one student put it, “like a fond and anxious father” watching his university grow up. Ezra’s health had already started to fail, however, and he died in December 1874, during my grandfather’s senior year.

I have a scrapbook, faded and flood damaged, that Henry started when he was at Cornell. There are several pages of mementos from his undergraduate years, including a $20 receipt for tuition in his final semester. I don’t know much about his life as a student, but it’s obvious that he was proud of the upset victory by the Cornell crew at the 1875 intercollegiate regatta in Saratoga. There are seven pages of newspaper clippings about the race in his scrapbook. (The campus celebration of that triumph, notes Bob Kane in Good Sports, gave birth to the cheer “Cornell, I yell, yell, yell, Cornell!”)

As a senior, Henry was named the Ivy Orator and delivered a lengthy speech during Commencement Week. “Classmates,” he began, “do you remember with what conscious pride, four years ago, we left our paternal homes, and became members of that corporate body known as college? What a sense of our independence possessed us! How important we felt!” (Some things never change.)

Henry graduated with a Bachelor of Philosophy degree and embarked on a career as a teacher and school principal in New York, Iowa, and Washington, D.C. He had three sons, the youngest of whom was my father, Alan Roberts, who earned a Cornell degree in civil engineering in 1922. Henry died while my father was still in high school, so he was unable to see his son (or a granddaughter and grandson who followed) receive a Cornell diploma.

Without the Morrill Land Grant Act, my grandfather’s life would surely have been much different. He might have stayed on the family farm or ventured to Rochester or Buffalo to work in a mill. Instead, he went to Cornell. The effects of this far-reaching legislation were profound—not just for higher education but for the nation as a whole, because of the social and cultural changes set in motion by the expansion of educational opportunity.

It’s easy to think of moments like the passing of the Morrill Land Grant Act in abstract historical terms. But when I look through my grandfather’s scrapbook and think about what coming to Cornell must have meant to him, the importance of those moments strikes home on a personal level. So, as our sesquicentennial approaches, I’m glad that this issue salutes the foresight of Justin Morrill in forging his landmark legislation, and that of Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White in capitalizing on the opportunity it presented to “found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study.”