![]() A scientist tackles 'hidden hunger'

A scientist tackles 'hidden hunger'

A scientist tackles 'hidden hunger'

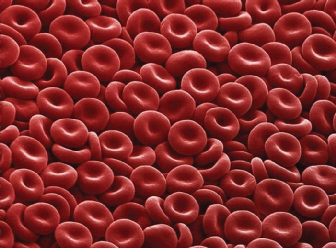

Anemia affects more than 1.6 billion people—nearly 25 percent of the world's population, most of them women and children. Caused by insufficient dietary iron, the condition manifests as a shortage of healthy red blood cells, the workhorses of the body's oxygen-transport system. Cognitive deficits and behavioral problems plague anemic children, while adults—most commonly, pregnant and lactating women—exhibit fatigue, depression, heart palpitations, and suppressed immune function as their organs suffer the cumulative insults of oxygen deprivation.

Jere Haas, the Nancy Schlegel Meinig Professor of Maternal and Child Nutrition and director of the Human Biology Program in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, has devoted more than two decades to describing how anemia—and the subclinical iron deficiency that precedes it—affects the human body, and assessing strategies for public health interventions. An anthropologist by training, he began his career nearly forty years ago with a broad interest in how micronutrient malnutrition—known by aid organizations as "hidden hunger"—affects everyday life in Latin America. In the Eighties, he began homing in on the relationship among iron, altitude, and hemoglobin in highland people of Mexico, Peru, and Bolivia.

Our bodies can't produce iron, making a balanced diet vital for staving off iron deficiency. Omnivores get what they need from meat; vegetarians who consume a wide variety of fresh fruits and vegetables can also maintain adequate stores. But among college-aged vegetarians subsisting on French fries and frozen yogurt, the precursor to anemia is almost as common as it is in rural, impoverished areas of the developing world. Haas recalls that when he sought subjects for his first laboratory-based investigation of iron deficiency's physiological effects, launched in 1994, recruiting enough participants on campus seemed like a long shot. "I thought I'd find maybe 10 percent if I was lucky," he says. Instead, he found that as many as 30 percent of the Cornell undergrads who joined the study were iron deficient. "It was a phenomenal number."

Haas had a hunch that the reduced productivity and depressed mood that plague those with full-blown anemia also afflict the nearly 2 billion people worldwide with the subclinical iron deficiency that often goes undiagnosed and untreated. To test the theory, he has combined meticulously controlled experiments in his Savage Hall laboratory with field studies throughout the world. "I wanted to show that iron deficiency caused a functional outcome," he says. "The best way is to have an intervention where half of the subjects get iron and half get a placebo." To enhance the social value of his research, he partnered with the nonprofit HarvestPlus to analyze their large-scale, international programs to combat hidden hunger. "It made sense to link my work with the applied question of delivery."

In parts of the world where grocery stores are ubiquitous, iodine in table salt boosts thyroid function, folic acid in breakfast cereal helps prevent fetal neural tube defects, and vitamin D-enhanced milk staves off rickets. Such micronutrient-enhanced processed foods have been a staple in the U.S. since the Twenties, transforming public health by making up for diets lacking the micronutrients that could also be supplied by the consumption of a rich array of whole foods. In developing countries, where subsistence diets include only a few staples, deficiency-related diseases run rampant. To fight back, HarvestPlus—with funding from the World Bank, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the U.S. Agency for International Development, among others—has launched plant breeding programs to boost the naturally occurring levels of iron, vitamin A, and zinc in rice, wheat, beans, maize, sweet potatoes, cassava, and millet.

In a nine-month, double-blind study in the Philippines, where up to 60 percent of women are iron deficient or anemic, Haas and the late John Beard, PhD '80, tested the effect of enhanced rice on blood iron levels in ten Roman Catholic convents. Despite their data revealing a clear positive effect of the fortified rice in boosting blood iron to healthy levels, Haas says much work remains for such selectively bred crops to improve public health. Although the nuns were more than willing to eat the rice, he worries that for the average woman struggling to feed her family, biofortified staples may be a tough sell— especially if selection for increased micro-nutrients diminishes the crop's appeal to local palates. As a co-principal investigator evaluating the efficacy of HarvestPlus's iron-fortified beans in Rwandan boarding schools, Haas will continue grappling with such questions for some time.

While Haas is fluent in Spanish and spends about 20 percent of his time overseas, little of it is in the field. Instead, he's made it a priority to partner with local scientists and government officials, including PhDs trained in his division who return to their home countries. "There's a phenomenal network of our graduates doing scientific research in the developing world," says Haas, whose former students include university and government scientists in Australia, England, Mexico, Peru, New Zealand, Nepal, Indonesia, Colombia, and Jamaica, as well as the U.S. "All of us who work in development recognize that we have to have partners who understand the politics and needs of the people. Local collaborators are the best—they know the answers on the ground."

— Sharon Tregaskis '95

{youtube}CNzZSW_ZWV0{/youtube}

Opinion: Hidden Hunger (Nicholas Kristof) (4:33)