I read with interest “Field of Dreams,” the essay in the July/August issue of CAM in which Courtney Sokol ’15 described her search for the perfect internship—a glittering berth that would not only yield a fun and interesting summer, but enhance her résumé and provide a gateway to a full-time job. But I had to smile. In my day, we didn’t have internships; we had summer jobs, and glittering they were not.

The summer after I graduated from Ossining High School in 1952, headed for Cornell, I worked in a small chemical plant not far from the town’s celebrated penitentiary. If OSHA had existed then, it probably would have closed the place in about four minutes. When not working on our little five-man assembly line making flux for soldering, we were in the yard emptying large jars of defective product to be reworked. It was necessary to rinse one’s arms continuously to avoid serious skin infections. When we occasionally did a form of electroplating that involved the use of cyanide, the quality of the protective gear was not overly reassuring. And, oh yes: the boiler did blow more than once, sending us all scurrying out into the yard.

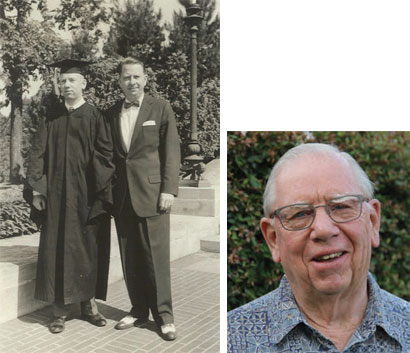

Way back when: Douglas Parker ’56, LLB ’58, with his father at his Cornell graduation (top) and today.

The following summer, my friend Roger and I worked in a complex of huge greenhouses devoted to growing roses. They were said to be among the largest rose gardens in the world, perhaps the largest, and we could believe it. Our jobs, weeding and watering, were not complicated, but July and August in a greenhouse is hot. Very hot. Hot enough so you’d have to take off your T-shirt and wring it out in your hands.

A year later, I took my agricultural skills up a notch to work as an assistant gardener at a local estate. But it was nearly my undoing—the only job from which I was ever fired. The disaster unfolded when I was pulling up some pansies to make room for new planting. The night before, four of us had traveled into New York for dates with some girls from out of town. The problem was that the girls had other commitments earlier in the evening, so our dates began after midnight and ended around 5 a.m. So I was tired, and inclined to rest a bit between pansies.

Suddenly, the head gardener, a dour Scot named Jock, appeared; from the look on his face, I could tell that all was not well. “I’m sorry to tell you, lad, I have to let you go.”

“Let me go?” I was incredulous.

“Aye, lad, the owner has been watching you work and she doesn’t think she’s getting her money’s worth. You can stay until the end of the week, but that’s it.”

Panic replaced incredulity. What would I tell my parents? How would I possibly get another job in the middle of the summer?

My pleas for mercy fell on deaf ears, but fate intervened. There was another assistant gardener—a fellow a few years older who, so far as I could tell, had made a career of drifting from one job to another. We didn’t have a lot in common, but got along well. And when he heard I’d been fired, he quit in protest. Thus, in one day Jock had gone from having two assistants to none. This, he was able to persuade the owner, was unacceptable—so, without missing a day, I was rehired. I finished the summer without further incident and at the end Jock allowed that I had straightened up and “done good.” High praise indeed, and a lesson or two learned.

The following summer, I worked mixing cement for artificial fieldstone on a shift from 1 a.m. to 9 a.m., a schedule to which I never became accustomed. The year after that, I drove a truck for a local laundry. (And not well; it had a tiny back window and no passenger side mirror, and I can’t recall how many times I bruised the rear fender.) Finally, after my second year of law school, I had an “internship”: summer associate in a large law firm. It was not quite having died and gone to heaven, but close enough, and it was the firm at which I would spend most of my professional career. Still, I look back on those earlier summer jobs with affection. And while I would gladly have traded all of them for fancy internships, I know I would have missed out on something valuable.