More than four decades ago, Susan Reverby ’67 was in Willard Straight Hall for a group burning of Vietnam draft cards when she was approached by one of her professors. “He stopped me and said that I was ruining ‘his’ university,” Reverby recalled recently. “And I said, ‘Excuse me, professor—whose university do you think this is?’ “

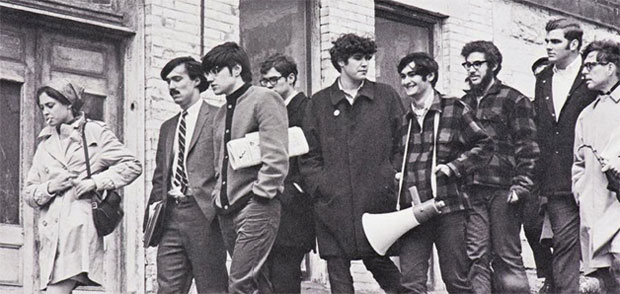

Peace march: Cornell students at an anti-war protest in December 1967. Bruce Dancis ’69, who’d been arrested the previous year for burning his draft are in front of Olin Hall, is at the center of the group, wearing a megaphone. Photo: Rare and Manuscript Collections/Carl A. Kroch library / Cornell University

That exchange has stuck with Reverby for years, in part because she herself joined the academy as a professor in gender studies at Wellesley College. Its central argument—whether radical activists should be considered part of the University community—was taken up again during a two-day reunion organized by government professor Isaac Kramnick and held on campus in November. Among the events Kramnick staged for “Vietnam: The War at Cornell” were panel discussions attended by hundreds of current students, a “teach-in” involving both sides of the antiwar debate, and presentations from the former activists during meetings of more than a dozen academic courses. Despite its name, the reunion didn’t just address anti-war activities on campus: participants also recalled conflicts over gender inequality, as well as the racial unrest that culminated in the Straight Takeover.

One of Kramnick’s main motivators in planning the gathering was showing students the trajectories of people like Frank Dawson ’72, who was involved in the Straight Takeover and now teaches at Santa Monica College, and Joe Kelly ’68, who was arrested several times for protesting but went on to work for the federal government in wildlife protection. The message? “It is possible to defy your government, go to prison, survive that, and have a healthy and happy life,” said Bruce Dancis ’69, who was on campus from 1965 to 1967 and was arrested after becoming the first student in the country to destroy his draft card (events he describes in his memoir, Resister, published in 2014 by Cornell University Press).

Many of the activists hadn’t set foot on the Hill since they were expelled—or banned from Tompkins County by a judge’s order. But Kramnick, who didn’t arrive on campus until after the height of the frenzy over the Vietnam War, said he wanted current students to come face to face with the Sixties radicals who braved expulsion and arrest for a cause. “It’s not my place to stand at the bully pulpit and say: ‘See these activists? You guys are not activists enough,'” Kramnick said, noting that the protesters’ stories “validate the idea that you could be a critic of the system and still not ruin your life.”

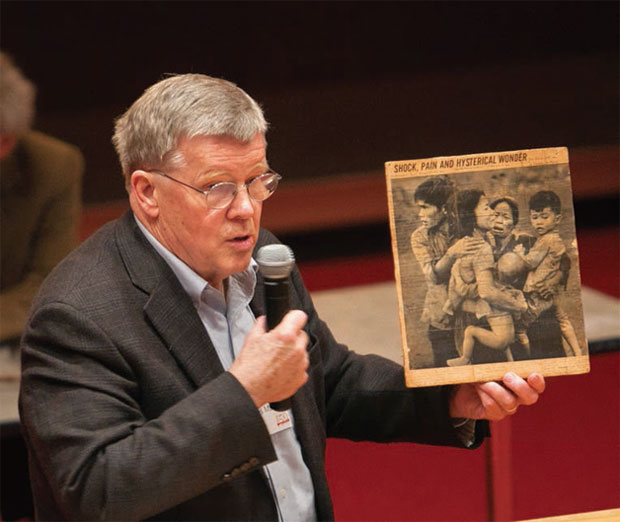

Never forget: Former English professor James Matlack speaks at the November reunion on campus. Photo: Koski

He first conceived the event about a year ago, when he and American studies professor Glenn Altschuler, PhD ’76, were polishing their book on the history of Cornell since 1940. Kramnick realized that there were dozens of members of the antiwar group Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) who had never been back to campus; meanwhile, he said, students today are “by and large politically apathetic” and disconnected from Cornell’s past. “Every speech you hear is about the future and the next new horizon for the University,” he said. “I wanted them to be introduced to a part of the University’s history that they knew nothing about.” Kramnick began by writing to about ten former activists scattered around the country, inviting them back to campus. The response was overwhelmingly positive. “Each of them had other names and suggestions,” Kramnick said. “It ballooned.”

For Kelly and others, the events—held, symbolically, around Veteran’s Day—represented a partial reconciliation after years of distance from the University. “It’s a little ironic to be invited back to speak when my last memory before leaving was standing in front of a Tompkins County judge who accepted a plea for scaling a fence—third-degree trespassing—in Barton Hall and hanging some flags over the ROTC cannon,” Kelly said. “The judge said, ‘I’m going to accept your plea, but don’t ever come back to Ithaca.’ ” Likewise, Ileana Durand ’72, BA ’74, was one of several who noted it was the first time they’d returned to campus since graduation. Durand, a Puerto Rican involved in protests calling for the University to do more to include minorities on campus, said she felt marginalized at Cornell and spoke of her anger at believing she had nothing to hold on to. “I never really had any support here; it was lonely,” she said. “The experience of being here was very difficult.” Being invited and coming back in November was a revelation, Durand said. A retired school teacher, she is now working to build a nonprofit focused on sustainability in Puerto Rico—a project she hopes will garner support from fellow alumni. “I thought there was nothing here for me,” she said, “but now I feel like I can use Cornell in a way I never have before.”

Kramnick noted that for years after the agitation of the late Sixties—and especially the Straight Takeover of 1969—”everybody’s feelings were raw for so long.” The divisions on campus, returning activists said, were often stark. Since then, some have been welcomed back into the fold—most notably Tom Jones ’69, MRP ’72, an architect of the takeover who later joined the Board of Trustees (he’s now a trustee emeritus). Dancis said that the November gathering was another indication that the University is accepting the dissenting voices as a key part of its history. “I do appreciate that Cornell is recognizing that we are part of its past, for better and for worse,” said Dancis. “They’re not sweeping it under the rug or avoiding it, and I think that’s a good thing.”

The distance may have narrowed, but it hasn’t closed entirely. Between events, a handful of the former protesters walked to the Sesquicentennial Commemorative Grove recently installed atop Libe Slope to celebrate the University’s 150th birthday. There, they found that the Straight Takeover is remembered for leading to the resignation of President James Perkins. “But we didn’t view it that way,” said Susan Rutberg ’70, who was a member of SDS as an undergrad. She and other former protesters, she added, would like the Grove’s wording changed to note that the takeover had been intended to make Cornell commit to more racially inclusive education, and that it led to the establishment of the Africana Studies Center.

For and against: The Society to Oppose Protestors (STOP) blocks vehicles carrying demonstrators bound for the Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam, held in New York City in April 1967. Photo: Rare and Manuscript Collections / Carl A. Kroch Library / Cornell University

Throughout the events, the activists’ stories often echoed each other; many revolved around campus landmarks (Barton Hall, Collegetown, the Straight) and rites of passage (orientation, Commencement) common to the undergraduate experience. At the same time, however, their memories of Cornell were inflected by an era that felt worlds away from that of the current students in the audience. They described a campus where some professors openly looked down on black culture and some white students felt that African Americans should express gratitude for simply being allowed to enroll. As Ed Whitfield ’70 recalled in a documentary about the Straight Takeover shown during the teach-in, one University department chair “said black folk had never made significant contributions to the history of the sciences or anything else . . . He looked up from his desk and said, ‘Can you read? Can you write? Have you ever written anything longer than a letter?’ ” In the same documentary, Irene Smalls ’71 remembered how a group of black female students were reported to the police for smoking marijuana—because of the odor of the chemicals they were using to straighten their hair. An economics professor, she added, once claimed that “black women are known for their promiscuity, and black women are known to have sex at an early age. And we were like: ‘Wait a minute.'”

It was that kind of environment, the former activists stressed, that pushed them to take drastic action against the University, culminating in the Straight Takeover that was publicized in nearly every major American newspaper. But though racial frustrations helped define the campus climate of the late Sixties, the divide over the Vietnam War was equally fraught, if not more so. James Matlack, an assistant professor of English during those days, talked about a promising young student from Texas, David Mossner ’68, who lived in Telluride House and took his course on Henry David Thoreau. “It was very clear that he was very much against the war,” Matlack said, “and wanted to live a life based on conviction, on principle, and on consistency.”

Almost a year later, Matlack learned that Mossner had stepped on a landmine while fighting in Vietnam and been killed instantly. It turned out that Mossner, fearing that he’d lose credibility if he dodged the draft, had joined the Army after graduation and quickly moved up the officer ranks. The professor went back to a book he had lent the young student; inside, he found Mossner’s draft card, only half burned. “And I could do nothing but grab it and weep, as I still do,” Matlack told a roomful of students in Uris Hall. “Not understanding, but realizing this is a young man that’s wrestling with the deepest aspects of this struggle, of this war, of what is right, of what he is called to do.” Two decades would pass before Matlack visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. “I ran my fingers over his name,” Matlack said, “to make real the young lives we had lost.”

Matlack also recalled the dramatic tale of Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, a former assistant director of Cornell University Religious Work who went underground after being sought by federal agents for destroying draft cards in Maryland. Soon thereafter Matlack helped organize a festival to celebrate Berrigan’s poetry, with 10,000 people packed into Barton Hall. The event was held near Easter and Passover, and a left-leaning rabbi visiting Cornell organized a “freedom Seder” as part of it. “And all of a sudden I see this figure of a motorcycle and helmet coming in . . . and it’s Dan,” Matlack said. “He’s in. And we know the feds are all over the place.” Berrigan—who was eventually arrested for that act of protest and many others, including symbolically “beating swords into plowshares” by hammering the nose of a nuclear missile at a General Electric plant—would continue to work for social justice and antiwar causes for decades to come.

Throughout the two days of events, many speakers warned against overly romanticizing the Sixties, which for many was a truly perilous time. Terry Cullen, MBA ’66, longtime coach of the Big Red sprint football team, served as a Marine leader on sweep operations in Vietnam. He was wounded and spent more than a year in a Navy hospital. At the teach-in, he described one mission in which he left with sixty-eight men and returned with four; the war, he said, was “God awful.” His best friend at Cornell vehemently disagreed with his decision to support military action in Vietnam, Cullen recalled, and the two argued about it constantly. At one point, they parted ways—Cullen to enlist, his friend to escape to Canada to avoid the draft. “All we talked about in the Sixties was Vietnam,” Cullen said. “That was the subject of every night, every class, everything that went on here.”

In large part, the war also defined Mary Jo Ghory’s years at Cornell. Not a well-known radical like Dancis or Jones, the 1969 alumna became increasingly involved in the movement while on campus. She worked with SDS, participated in antiwar protests, and appeared on the front page of the Daily Sun for trying to throw paint at Marine recruiters in Barton Hall. (Ghory slipped, and the paint missed its mark—but she was still arrested and sentenced as a youthful offender.) Yet Ghory also spent enough time at the books to earn admission to medical school after graduation— the path her father had urged her to take—eventually becoming a pediatric surgeon. “Sooner or later I came to the realization that I would live to be thirty,” she said, “and that maybe my father was right.”

For Daniel Marshall ’15, a history major who helped Kramnick organize the event, the decision of those like Ghory to pursue fruitful careers should not be taken to mean that their radical ideas were misplaced. Now at work on an honors thesis about Cornell in 1969, he has spent months poring over archives, transcripts, and speeches from the era. Marshall said that although Sixties radicals are sometimes maligned for trading their activism for successful careers, such criticism is fundamentally unfair. “You certainly did change society, but the fact that you didn’t do so once and for all doesn’t mean you failed,” Marshall said at the teach-in in Uris Hall. “It just means we’re still fighting.”