When Marine Captain Adrian Kinsella ’08 was deployed to Afghanistan in 2010, an interpreter named Mohammad was attached to his unit. The two men grew close during Kinsella’s seven-month tour, and it was hard to say goodbye.

In Afghanistan, Kinsella’s unit endured roadside bombs and occasional small arms fire, but returned safely; he describes his deployment as mostly a peaceful, “hearts and minds” type of operation. His first real battle began stateside, when he applied for a visa for Mohammad to come to the U.S. to escape retaliation from the Taliban for his service to the American military. “He was an exceptional interpreter and one of the bravest men I’ve ever worked with,” says Kinsella, now a third-year law student at Berkeley training for a career as a Marine judge advocate. “We were lucky to have him, and I wasn’t going to leave him in mortal danger.”

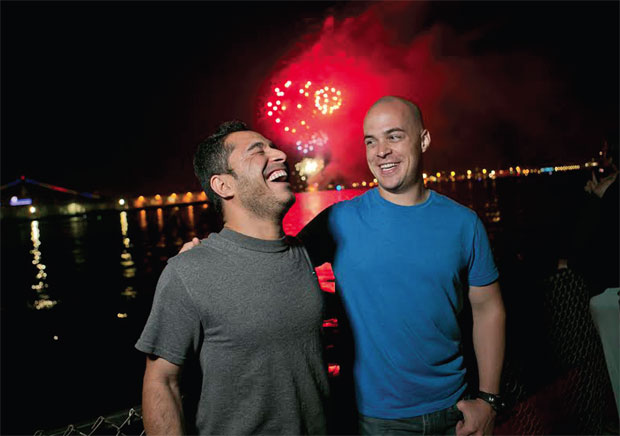

Best buddies: Adrian Kinsella ’08 (right) celebrates Fourth of July with his roommate and former translator, Mohammad.

Under a system known as the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program, the State Department has pledged to assist Afghan and Iraqi citizens who helped American forces in the post-9/11 wars. But by 2012, only 12 percent of a proposed 1,500 annual visas had been granted. It took three and a half years for Mohammad—whose last name Kinsella asked be withheld for security reasons—to be freed from bureaucratic limbo. “I thought the whole process would take maybe three months,” he says. “But the red tape and lag time were staggering.”

A Seattle native who studied philosophy and classics on the Hill, Kinsella abides by the Marine motto “semper fidelis”—always faithful—and the Corps’ commandment to leave no one behind. In that spirit, he was relentless in his efforts to get Mohammad out of Afghanistan. After repeatedly seeking assistance from members of Congress, nonprofits, and other supporters, he eventually helped persuade the U.S. government to honor its commitment to a man Kinsella calls “my brother.”

‘I thought the whole process would take maybe three months, but the red tape and lag time were staggering.’These were not the sort of battles that Kinsella envisioned when he enlisted. He joined, he says, because, “I’d been so privileged and received so much, I felt responsible to give something back.” During his Cornell days he lived in Telluride House, studied abroad in Paris, helped excavate Neolithic pottery at an archeological dig in Greece, rowed lightweight varsity crew, and volunteered with the Cayuga Heights Fire Department. Five days after graduation, he reported to Officer Candidate School in Quantico, Virginia.

By the time Kinsella and his interpreter met in 2010, Taliban reprisals had already led to the brutal death of Mohammad’s father. After being tortured for information about his son, he was murdered and his mutilated corpse tossed into a river. By the time his remains were found, his wife only recognized him by the sandals he wore; they were a gift from Mohammad.

Kinsella first got a call for help in 2011, when he was back in the U.S. Two years later, the Taliban abducted Mohammad’s toddler brother, holding him for a ransom that the kidnappers demanded be placed on their father’s grave. “Mohammad was frantic and afraid for his family,” says Kinsella. “And I was afraid for his life.” The money—about $35,000, most of Mohammad’s earnings from interpreting—was paid and the boy returned; the child was severely dehydrated and couldn’t speak for days. The family fled to another country. It was there that Mohammad finally got his visa, and the two men were reunited at the San Francisco airport in January.

As Mohammad said in a recent phone interview: “Because of me, my family is not safe anywhere.” Securing their entry into the U.S. is Kinsella’s latest uphill battle. “We just re-sent the paperwork, again, to the immigration service,” he says. “The first time, they said we did not adequately prove Mohammad’s family’s level of financial hardship and sent the whole 300-page application back.” Kinsella has learned to bite his tongue. But he admits that the pro cess is exhausting and discouraging. The first rejection letter, he notes, demanded W-2s and tax returns. “Moham mad’s fam ily cannot leave their house,” says Kin – sella. “They are unable to leave their house and live as if in a prison, in constant fear of a third Taliban reprisal. How can they produce tax returns?”

Mohammad says he doesn’t regret his service, but doesn’t know how he’ll explain the death of his father to his little brother, now five. “Will he hate me for what I did for my country,” he wonders, “or love me?” Despite his family’s perilous situation, Mohammad knows he’s among the lucky ones. He got a job as a technician, earned his driver’s license—on his third try, Kinsella notes with a laugh— and now rooms with Kinsella and another friend in Berkeley. But with the prospect of another U.S.-led invasion of Iraq looming in the battle against ISIS—and along with it the potential for redeployment— Mohammad worries about his best friend. “If he goes back, I want to go with him,” he says. “I want to help protect him. I owe him my life.” Kinsella sees it the other way around; Mohammad’s work, he says, was instrumental in helping his Marines return safely.

Kinsella and Mohammad have traveled to Washington, D.C., to lobby for other stranded interpreters; thousands of Iraqi and Afghan citizens who aided the U.S. military are thought to remain at risk. In August, Congress passed a rare bipartisan bill that added another 1,000 visas to the SIV program—but unless lawmakers vote for an extension, the program will close at the end of December. “We made a promise to people like Mohammad and his family,” says Kinsella. “As a Marine, as a human being, I feel it is my responsibility to see it fulfilled.”