So it would seem that the baby gestated by the Morrill Act was born—but it was not to be quite that straightforward. Some New York colleges, notably Columbia and Union, looked with disdain at the terms of the act; agricultural and engineering education were outside their sphere of interest. But other colleges saw possibilities.

There were two leading contenders. One was the Ovid Agricultural College, sponsored by the New York State Agricultural Society, of which Ezra Cornell was a prominent member. The other was the People's College in Havana (now Montour Falls), sponsored by Charles Cook, an influential state senator. Cook got the bid and began preparations to meet the terms imposed by the state: within three years, the college should have ten competent professors in agriculture and the mechanic arts, be able to accommodate 250 students with proper equipment, and have a working farm of 200 acres and workshops to support mechanical activity and innovation.

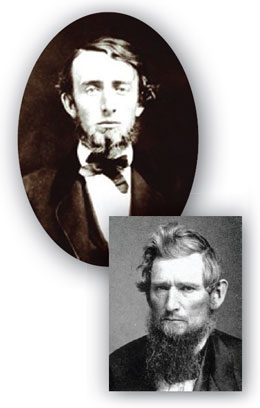

Then came an auspicious occurrence. In the fall of 1863, young Andrew Dickson White of Syracuse was elected to the State Senate, as was Ezra Cornell from Ithaca. White became chair of the Committee on Literature (meaning education) and Cornell the chair of the Committee on Agriculture. The two men—the Senate's youngest and oldest members—were in Albany when the body convened on January 2, 1864. White reported that Mr. Cornell "was steadily occupied, and seemed to have no desire for new acquaintances."

'The enterprise expands from an Agricultural College to a university of the first magnitude,' Cornell wrote in 1865.They were soon brought to each other's attention by the Cornell Library bill that landed on White's desk for approval. Cornell, a believer in the power of education, had endowed a free public library for the people of Tompkins County, and its charter of incorporation needed Senate approval. White was impressed by Cornell's "breadth and largeness" in framing the terms of the library and with his wisdom in selecting as trustees "the best men of his town," political opponents as well as friends. White felt drawn to the older man.

Cornell, for his part, was concerned about the progress being made by the People's College to fulfill its requirements as the state's land-grant school, because Charles Cook had suffered a stroke—stilling the pen that wrote the checks for his institution. Supporters of the Ovid Agricultural College also watched the stalled process in Havana and began to make their own plans. In January 1864, Judge J. C. Folger of Geneva introduced a bill that proposed to halve the People's College's share of the land grant, suggesting that the other portion go to the Ovid institution. This bill landed on the desk of Senator White, who immediately tucked it away in a drawer.

White was a thoughtful and scholarly young man, a graduate of Yale who had studied in European universities and taught at the University of Michigan until he was called home because of his father's illness. He believed in big ideas that he called "air castles" and thought the state deserved better than half measures.

There were few who wanted to buy state scrip during wartime, even with the price as low as $1.25 per acre and gradually dropping. Cornell inserted himself into this situation by suggesting that men of good will should buy scrip and claim the finest land, then hold it in trust for their colleges. He offered to supply a tenth of the necessary funds, but no one else came forward.

Born to a simple family and poor throughout much of his adult life, Cornell was not an avaricious man. Having come into money through his connection with Western Union Telegraph, his greatest care, he wrote, was "how to spend this large income, to do the most good to those who are properly dependent on me, to the poor and to posterity." The Cornell Library was his first effort.

In September 1864, Cornell invited White to an Agricultural Society meeting in Syracuse. Because Folger's bill had not come to the Senate floor—being safely locked in White's desk—the Ovid Agricultural College was about to announce its own demise. Cornell had other plans. He arrived at the meeting with a proposal: if the Agricultural College trustees would locate the school in Ithaca, he would donate his 300-acre farm on East Hill, erect suitable buildings, and donate up to $300,000 on the condition that the state legislature would endow the college with $30,000 per annum from the Morrill fund.

According to White, there was great applause from those assembled—until he stood up and refused the terms that Cornell had outlined. White was opposed to dividing the land-grant funds, but promised that if Cornell and his friends would ask for the "whole grant—keeping it together" and add Cornell's $300,000, he would support the bill with all his might. The goal, he pointed out, was to have the best university in the world, and though it did not necessarily please White—who offered half his own fortune if the university were sited in Syracuse—this new institution would be located in Ithaca. At a subsequent meeting that was boycotted by representatives of the People's College, Cornell increased the amount of his donation to $500,000.

There were still hurdles to be overcome, of course. Time had not yet run out on the People's College, and there were more than twenty small colleges in the state that hoped they might in some way benefit. (One hung on long enough to threaten to stall the charter and received a payment that Cornell called blackmail.) And what about the interests in Ovid? As the story is often told, the buildings there eventually became the Willard Asylum for the Chronically Insane, later called the Willard State Hospital, something that Dr. Sylvester Willard had long argued for—but was granted only after he died in front of a legislative committee while pleading his case.

While White had long thought about creating an ideal university, for Cornell the idea was novel and thrilling. In January 1865 he wrote: "The enterprise expands from an Agricultural College to a university of the first magnitude."

A month later, White introduced a bill in the State Senate "to establish the Cornell University, and to appropriate to it the income of the sale of public lands granted to this state." The fight was on, fought fair and foul on all sides—but even with an extension of three months, the People's College could show no progress. The Cornell charter underwent revisions, including new wording (inspired by the Land Grant Act) to insure that the institution shall "teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, including military tactics, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions of life. But such other branches of science and knowledge may be embraced in the plan of instruction and investigation pertaining to the university as the trustees may deem useful and proper."