Last March, nine Cornell undergrads spent their spring break in Florida—not on a beach, but helping economically disadvantaged students at an Orlando elementary school. The Cornellians volunteered in Tangelo Park, a predominantly African American neighborhood where Orlando hotel magnate Harris Rosen ’61 has founded a program that offers everything from free preschool to college scholarships.

Last March, nine Cornell undergrads spent their spring break in Florida—not on a beach, but helping economically disadvantaged students at an Orlando elementary school. The Cornellians volunteered in Tangelo Park, a predominantly African American neighborhood where Orlando hotel magnate Harris Rosen ’61 has founded a program that offers everything from free preschool to college scholarships.

Nine undergrads spend spring break in Orlando— but instead of riding on Space Mountain, they do long division

By Beth Saulnier

Photographs by Chad Pilster

Spring break. The phrase conjures images of collegiate bacchanalia, of sandy beaches and frozen drinks —beer pong, wet T-shirt contests, frat boys behaving badly and sorority girls gone wild.

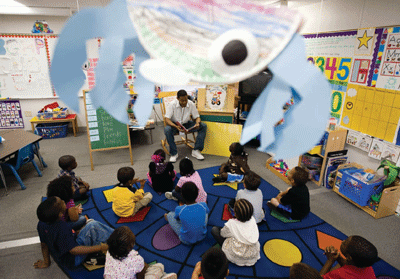

That is not Micah Bell's spring break. Though she is indeed in Florida, the petite African American junior is clad in a demure blouse and slacks—no string bikini in sight—as she perches on a stool in a first-grade classroom in Orlando's Tangelo Park Elementary School. Beneath posters declaring the colors, days of the week, and letters of the alphabet, she reads aloud from a book called Johnny Appleseed & the Bears; when she's done, she passes out construction paper—pink for the girls, blue for the boys—so they can draw their own bear pictures. "We are not rude," teacher Lillie Ward reminds the students as they jockey for the stash of colored pencils. "We share and we don't yell."

It's called Alternative Spring Break, and the name says it all. Each March, the Cornell Public Service Center offers more than a dozen community service trips for students who crave something different from the traditional sun and sand (or channel-surfing on their parents' couch). Most of the trips are fairly close to campus—students work at an LGBT service center in New York City or an organization battling homelessness in Philadelphia—but some go farther afield, like to a women's shelter in West Virginia. Says program executive director Leonardo Vargas-Mendez: "These are great opportunities for students to apply the theoretical learning that happens in the classroom."

For the past two years, the University has sent students to Orlando to work as mentors and teachers' aides in Tangelo Park, the focus of an educational initiative by local hotelier Harris Rosen '61. He puts the students up in his 1,500-room Rosen Shingle Creek golf resort and convention hotel; the property, rated four diamonds by AAA, is a short drive from Tangelo Park—a working-class, predominantly African American neighborhood of modest single-family homes where 85 percent of students qualify for free or reduced lunch.

In 1994, Rosen founded the Tangelo Park Pilot Program to aid the neighborhood via free home-based preschool, scholarships to Florida's public universities, and a community resource center—programs that benefit Tangelo Park kids from age two through college graduation. "This is not something where the Great White Knight comes in and says, 'I'll change your lives for the better,' " Rosen says. "This is saying, 'I have an idea, but we're going to have to work together.' " Today, citing research by a University of Chicago economist, he says that the Pilot Program generates seven dollars in community benefits for every dollar spent. "The return on investment is huge," Rosen says. "If we took 1,000 neighborhoods and spent approximately what we spend a year—a maximum of $2 million to $3 million—dear God! Is it better to spend that helping these kids and changing our society, or giving bonuses to fat cats? It's surprising to me that other successful, wealthy individuals are disinclined to do things like this—I never could fathom that."

A series of humble, low-slung, Sixties-era buildings connected by covered walkways, Tangelo Park Elementary is a study in how staff dedication and the right resources can make an enormous difference in kids' lives. On the Cornell students' first day there, for example, the fifth graders are about to begin the science portion of the dreaded Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test. But rather than going straight from the bus to the classroom, they start the day with a breakfast of sausage biscuits (Rosen often underwrites test-day meals) in the cafeteria, where principal Tashanda Brown-Cannon leads a pep rally and a moment of meditation. Then they march to the test en masse, clad in gold Tangelo Park Tigers T-shirts, clutching bottles of water and fruit snacks to keep their energy up.

The school's motto—"Excellence is the only option"—is nearly as ubiquitous as the images of Barack Obama, who appears on numerous posters and computer desktops. Brown-Cannon notes that from 2006-07 to 2007-08, the number of students who passed the science FCAT more than doubled, from 16 percent to 33 percent, and that Tangelo Park had the fourth-highest improvement rate in reading and math scores among central Florida elementary schools. "All of the teachers and staff members are interested in seeing the students succeed, and they're willing to do whatever it takes," says Brown-Cannon. "If they need to feed a child, take a child home, counsel a parent—they are willing to do it so that the whole child is successful. It's important that we just get in and do what needs to be done with happy hearts."

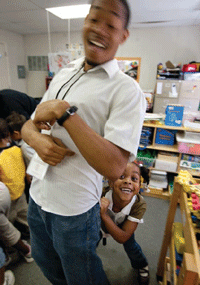

The nine Cornell undergrads and one law student who spend their break in Tangelo Park find themselves transported back to their grade school days: those working with younger kids romp with them on the playground or fashion bunnies from construction paper and cotton balls, while those assigned to older grades help unravel the mysteries of polygons, fractions, and long division. With Easter on the horizon, junior Marc Hem Lee sits in a rocking chair and reads the cautionary tale Little Rabbit Foo-Foo—in which the title character pays a dire price for "bop-ping" his fellow forest creatures on the head—to a rapt audience of pre-kindergarteners. Speaking in the lilting accent of his native Trinidad and Tobago, Hem Lee indicates each line in the oversized volume with a pointer that has a puffy glove at one end. Later, during play time, he flips plastic pancakes on a toy stove and has an imaginary conversation on a stuffed princess phone, then heads over to a fifth-grade classroom to help make a model of the solar system. "The way I look at life is that you learn and grow based on your experiences," says Hem Lee, a theater arts major who plans a career in medicine. "I chose to go to Tangelo Park to do this sort of volunteer work so that it would help me grow as a person. It was fun and I learned a lot. Everyone was so kind and welcoming to us, and thankful that we were there to help."

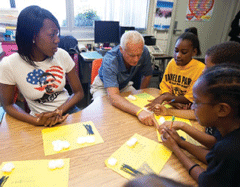

In addition to their hands-on work in the classroom, the Cornell students—most of whom are African American—serve as role models, showing the children that, regardless of race, hard work can get them to college. And even though most of the kids come from families of limited means, a college education is more than just a pipe dream: as long as they live in Tangelo Park when they graduate high school, Rosen will pay their way through any public university in the state. "For students in poverty to be successful, it's important that we provide hope," says Brown-Cannon, "and that free college education is a source of hope for all of our students." According to the principal, the very fact that the Cornell students are willing to spend their vacation in Tangelo Park sends a powerful message. "It shows students how important it is to give back," she says, "how important service is to the community."

On the Wednesday of spring break, Rosen visits the school, going from classroom to classroom trailed by two photographers and a cameraman from the local TV news. He drops in on a fourth-grade science lesson where students are using construction paper, yarn, and cotton balls to illustrate evaporation, precipitation, and condensation. "Rain starts in a cloud," Rosen says as he admires their work. "We need rain right now, don't we?" He smiles at Jillian Greenaway '10, a human development major clad in an Obama T-shirt. "This young lady goes to a very fancy college," he tells the kids. "Is everybody going to a fancy college one day? OK, you guys be good!" He heads to another classroom, stopping to clean some dead leaves off the concrete walkway. Over in the third grade, the students are modeling the spinal cord with circular pasta and gummy Life Savers. "Are real backbones made out of Life Savers and pasta?" Rosen asks them. They respond in unison: "No, sir!"

During their week in Tangelo Park, the Cornell students also get a look at other elements of the Pilot Program. They visit the home-based preschools that Rosen set up, hear a talk by a University of Central Florida professor on empowering African American parents, and meet with a group of college-bound students at the local high school. "Do you have to be, like, a genius to get into Cornell?" one teen asks during the question-and-answer session, which covers such topics as fraternities, sports, GPAs, and the size of dorm rooms. Bell—a Fort Lauderdale native and the only Florida resident among the Cornellians—is a focus of interest, fielding variations on the same question: How cold is it up there, really?

During their week in Tangelo Park, the Cornell students also get a look at other elements of the Pilot Program. They visit the home-based preschools that Rosen set up, hear a talk by a University of Central Florida professor on empowering African American parents, and meet with a group of college-bound students at the local high school. "Do you have to be, like, a genius to get into Cornell?" one teen asks during the question-and-answer session, which covers such topics as fraternities, sports, GPAs, and the size of dorm rooms. Bell—a Fort Lauderdale native and the only Florida resident among the Cornellians—is a focus of interest, fielding variations on the same question: How cold is it up there, really?

Practically from the moment she walks into Ward's first-grade classroom, Bell has a strong rapport with the kids, who call her "Miss Micah" and greet her with hugs. The daughter of Michael Bell '83 and Janet Matthews Bell '82, she has done Alternative Spring Break every year, previously working for an ACLU youth rights program and a housing development agency, both in New York City. "I feel like I'm doing something useful during my break, something that is affecting other people," she says. "I'm not just lounging and relaxing, I'm learning—and that's what college is about. If I can extend that into spring break, it's actually a benefit, so I don't think I'm missing anything at all." (And in fact, the trip isn't all work and no play: in addition to enjoying the amenities of Rosen's resort, the students get to spend a Sunday at Sea World and an evening at Universal's CityWalk entertainment complex.)

Bell, who plans to work for Teach for America after graduation and eventually earn a law degree, gets many valuable lessons in tending to first-graders from Ward, a formidable woman with dyed red hair who took up teaching after twenty years as a corrections officer. Asked the inevitable question—how much difference is there between overseeing inmates and six-year-olds?— she laughs. "Not much," she says. "You get what you give. You give respect, you get respect."

Ward brooks no disobedience from the children, gently correcting them when they fidget while sitting on the floor for a lesson. "Criss-cross, applesauce!" she tells them in a singsong voice, reminding them to sit cross-legged and pay attention. "I think it went well," Bell says at the end of the week. "Our last day, people got emotional. I think it made a big impact on everybody. I loved meeting the students and I'm really going to miss them. It was a good experience, and it was nice to be able to provide a service to a community in need."