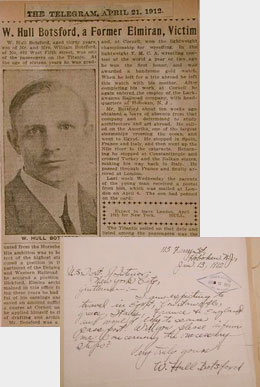

Back in Elmira, Hull Botsford's parents hadn't expected him to return so early from Europe. Although he was listed among the missing, a headline in the April 23 edition of the Newark Evening News read "CLINGING TO HOPE SON DIDN'T SAIL ON Titanic." There is no record of Botsford's last hours, but he was among the more than 1,500 who perished, and the more than 1,200 whose bodies were never recovered.

Botsford's younger sister, Talitha, only eleven at the time of his death, became an artist, poet, and musician (studying violin at Ithaca Conservatory of Music) who would live to 100. She is buried beneath a double monument—for herself and her brother. In her last days, she would come to know a man named John Pulos, an amateur Titanic historian who has planned a two-day centennial Titanic festival for April in Watkins Glen. Talitha gave Pulos the last of her brother's things that she'd kept—some postcards he had sent from Europe, architectural drawings, a photo Botsford had taken of his family in front of Goldwin Smith Hall. Tabitha told Pulos that her father was so devastated by the loss of his son that the family was never allowed to talk about it. She was certain, though, that her brother would never have taken a seat in a lifeboat when others could have been saved—a belief that was echoed in a eulogy given by his friend A. G. Hallock, BArch 1911. "He left a record of modesty and unselfishness which led his friends at the very first to give up hope that he might have been rescued," said Hallock. "He would have thought of first the women and children and then of those having greater responsibilities than he."

Aboard the RMS Carpathia, the ship that rescued the survivors on Titanic's lifeboats, a woman approached Leila Meyer and told her that her husband had done just that. The woman, a passenger on the last lifeboat launched, said that Edgar Meyer behaved "like a gallant gentleman and a hero." Meyer, two other passengers, and some crewmen had helped the last evacuees into the boat and lowered it over the side, the ship already low in the water. As the lifeboat drew away, they began making their way toward the stern with their lifebelts on. It was the last anyone saw of Edgar Meyer.

Two weeks later, Leila's brother was married in a small, quiet ceremony. By 1915, when her first husband's estate was settled (she inherited more than $500,000), Leila was remarried and living on Park Avenue. Meyer's parents, meanwhile, donated $10,000 to Cornell for endowment of the Edgar J. Meyer Fellowship in Engineering Research, which acting Cornell president T. F. Crane described as an appropriate way of preserving "the memory of such a fine life and noble death."

The two Cornellian survivors went on to long lives. Gilbert Tucker moved to a forty-acre estate outside Albany a year after the disaster—the same year that the woman who drew him to Titanic, Margaret Hays, married a physician. Tucker was married in 1922 and went on to publish several books touting Georgist philosophy, emerging as a vehement anti-socialist. He died at eighty-seven, living out his last days on California's Monterey Peninsula, along the Pacific Ocean.

Norman Chambers lived to eighty-one. He and Bertha had no children, nieces, or nephews. But later in life, after Bertha passed away and Norman was remarried to a divorcée, he became a stepfather and stepgrandfather. Known for appreciating life's simple pleasures, he died of a stroke while vacationing in Portugal with his second wife. Later, his stepdaughter would tell a Titanic historian about his generosity and kindness. "Like the ripples from a stone thrown in the water," she said, "so his goodness continues to spread."

Many of the CAM stories written by contributing editor Brad Herzog '90 through the years can be found at www.bradherzog.com.