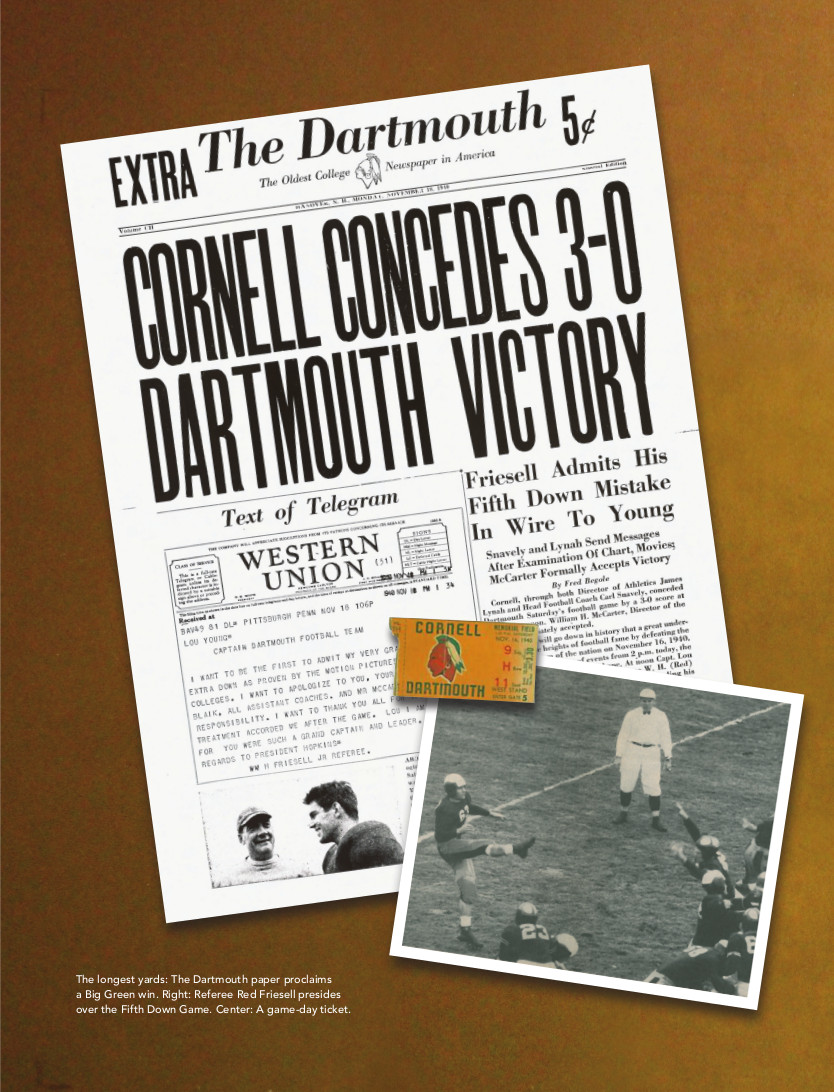

The longest yards: The Dartmouth paper proclaims a Big Green win. Right: Referee Red Friesell presides over the Fifth Down Game. Center: A game-day ticket.

Most of the key players are gone now, outlived by the drama that unfolded seventy-five years ago this November. But stories are immortal, and for years the members of the 1940 Big Red football squad told and re-told the tale of what generations would come to know as the Fifth Down Game: the moment when the University forfeited a key victory, choosing ethics over glory. In the history of Big Red sports, it was both the most heartbreaking loss and the most enduring victory.

Three-quarters of a century have passed, and most pre-war sports headlines have faded into history. Who remembers which team won the 1940 college football national championship? How about that year’s Heisman Trophy? But people still talk about a game played that fall between Cornell and Dartmouth before a half-capacity crowd in Hanover, New Hampshire.

A decade ago, ESPN football historian Beano Cook ranked the most important moments in the sport’s history. He placed the Fifth Down Game second, behind only the famous “Win one for the Gipper” speech (which happened to be immortalized on the silver screen that same autumn in 1940). But while George Gipp’s quotation may well have been apocryphal, the Fifth Down Game is in the record books. Twice, you might say.

A decade ago, ESPN football historian Beano Cook ranked the most important moments in the sport’s history. He placed the Fifth Down Game second, behind only the famous “Win one for the Gipper” speech (which happened to be immortalized on the silver screen that same autumn in 1940). But while George Gipp’s quotation may well have been apocryphal, the Fifth Down Game is in the record books. Twice, you might say.

In an era when scandals like Deflategate and the Lance Armstrong doping case demonstrate that athletes are sometimes willing to bend the rules for the sake of victory, the story of how one college football program chose to do the right thing resonates. Today, it may seem a quaint tale. But it serves as a reminder of the fact that in sports, as in life, winning isn’t everything.

On September 16, 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt signed into law the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. The Nazis had plowed through France, and a once-sanguine American public feared what might come next; nearly two-thirds of Americans believed that Hitler’s bid for domination wouldn’t stop on the Eastern side of the Atlantic. The sports pages offered little distraction. Wimbledon and both the Summer and Winter Olympics had been cancelled. But one story did capture the attention of sports fans across the nation: a football team from Ithaca that just wouldn’t lose.

Key players: (Top row, from left) Walt Matuszak ‘41, DVM ’43; Walt Scholl ‘41; Bud Finneran ‘41; Ray Jenkins ‘42; Hal McCullough ‘41. (Bottom row, from left) Lou Conti ‘41; Mort Landsberg ‘41; Nick Drahos ‘41, MS ’50; Bill Murphy ‘41.

Only five years earlier, Cornell had been luckless. Coach Gil Dobie left for Boston College, saying, “You can’t win games with Phi Beta Kappas.” But then Carl Snavely took the reins and the team’s fortunes turned. In 1938, the Big Red lost only once. The following year, Cornell went 8-0 (beating Big Ten champ Ohio State along the way) and finished the season ranked fourth in the country by the Associated Press. With nearly every star returning for the 1940 campaign, Stanley Woodward of the New York Times wrote, “Theoretically this Cornell team is one of the greatest that has ever stepped out ready made on a football field.”

On October 16, after Cornell had won its first two games by a combined score of 79-0, every player over the age of twenty-one lined up with nearly 1,500 other male Cornellians at six draft registration booths on campus. Three days later, five Big Red players scored touchdowns in a 33-6 rout of Syracuse, after which opposing coach Ossie Solem deemed Cornell’s “the greatest passing attack I’ve ever seen.” The Big Red was ranked number one in the nation, earning more than twice as many first-place votes as Notre Dame. On October 26, more than 30,000 fans at Schoellkopf Field watched another victory over Ohio State. After a 27-0 win over Columbia the following week, one Iowa newspaper announced, “CORNELL APPEARS CINCH TO HAVE UNBEATEN SEASON.” The next Saturday, Cornell beat Yale 21-0.

But harsh realities from the wider world cast a shadow over that autumn. On the day that the Fifth Down Game would be played—November 16, a week and a half after FDR was re-elected to an unprecedented third term—the U.S. awoke to the news that more than 500 German bombers had all but destroyed the British city of Coventry. The war was going badly. America’s sons—including Cornell’s football stars—seemed destined for the battlefields of Europe.

Indeed, by the end of the war, Walt Scholl ’41—the second-stringer who threw the Fifth Down Game’s fateful fourth-quarter pass—had flown seventy-two missions over the Mediterranean, earning a Distinguished Flying Cross. Teammates Frank “Bud” Finneran ’41 and Ray Jenkins ’42 rose to the rank of Marine captain and were awarded Bronze Stars. Hal McCullough ’41 single-handedly wiped out a machine gun nest and captured a group of German soldiers. Lou Conti ’41 served seventeen months as a bomber pilot in the South Pacific; Mort Landsberg ’41 flew fighter planes alongside future President George H. W. Bush; Nick Drahos ’41, MS ’50, served on the French front as a demolitions expert.

Then there were the men who didn’t come home. Landsberg lost a brother, who was shot down over the Ryukyu Islands. Snavely lost his son, Carl Jr. ’42, whose bomber disappeared off the coast of Newfoundland. And Ed Van Order ’42, the only junior to start on the 1940 team, perished on Okinawa three months before the war’s end.

In Honor on the Line, a chronicle of 1940 and the Fifth Down Game that Robert Scott, MRP ’73, and Myles Pocta self-published in 2012, the authors describe the season as players enjoying “their last gridiron fling before war overtook them—and took over their lives.” Such was the setting on the third Saturday in November, when a group of red-clad teammates—having won eighteen straight games—trekked to Dartmouth’s Memorial Field on what was, by all accounts, a meteorologically miserable day.

The contest seemed a mismatch. Cornell had the nation’s most potent offense, outscoring its opponents 181-13, while the Big Green had won only three games out of seven. But Dartmouth—they were known as the “Indians” then—had been focusing on this match-up since a 35-6 trouncing in Ithaca a year earlier. Immediately following that game, Coach Earl Blaik had announced his priorities: “Gentleman, next year there is only one game on the schedule—Cornell.” And then there was the weather. Four days of rain and a dusting of snow had turned the field into a sloppy mess. And as the New York Times had noted, “In football, mud is the great equalizer.”

It was 0-0 at the half. Cornell couldn’t muster an offense; Dartmouth, which attempted only one pass all day, pushed into Big Red territory several times, but failed to score. In the third quarter, Cornell finally moved the ball deep into Dartmouth’s end of the field, but a pass was intercepted in the end zone. It was still a scoreless game until the final quarter, when a Dartmouth field goal made it 3-0.

Led by Scholl off the bench, Cornell mounted one final desperation drive. By the time he completed a pass to halfback Bill Murphy ’41, making it first and goal at the six-yard line, there were only forty-five seconds left on the clock. And here began the series of plays that would become the stuff of confusion, controversy, conversation—and eventually, legend.

First down: Landsberg ran for three yards.

Second down: Scholl carried the ball to the one-yard line.

Third down: Landsberg again, diving forward into a mass of players.

Right guard Conti would later insist that Landsberg had scored, but the ref didn’t see it that way. W. H. “Red” Friesell Jr. stood five feet tall, but he’d established an outsized reputation in his two decades as an official. If Army played Navy, if Harvard played Yale, if Cornell was trying to continue an eighteen-game unbeaten streak, then Friesell was working the game.

No touchdown, he signaled, and placed the ball about a foot from the goal line.

The Big Red asked for a time out, but it had none left. Friesell called a delay of game penalty and marched the ball five yards back to near the six-yard line. In a normal scenario—fourth down, losing 3-0 with only ten seconds remaining—Cornell might have attempted a game-tying field goal. But even a tie would likely have dashed hopes for a national championship (which was awarded by a vote of Associated Press sports writers and usually went to an undefeated team), so the Big Red went for the win. Scholl rolled to his right and tossed the ball toward the end zone. When it was batted down by a defender, the Dartmouth fans erupted in celebration.

Game over. But then it wasn’t.

Friesell grabbed the ball, walked a few steps, then stopped suddenly and conferred with the head linesman. There were no penalty flags in those days, so there’s no clear visual record of exactly what happened on that play. Dartmouth players insisted it was an incomplete pass on fourth down. Cornell captain Walt Matuszak ’41, DVM ’43, was equally adamant that the fourth down had to be replayed because both teams had been called offside. Whether that was the case or the officials simply lost track of downs, Friesell marched the ball back to the six-yard line and signaled that it was Cornell’s ball. Again.

With three seconds left on the clock, Cornell tried the exact same play. Legend has it that Murphy whispered, “Dear Lord, if you let me score this touchdown, I promise to attend Mass every day for a year.” This time, he caught the pass in the end zone just before falling out of bounds. The clock ticked to zero, Drahos kicked the extra point, and Cornell won 7-3. But given what soon developed, Murphy would have to seek clarification from his priest.

In the game’s immediate aftermath, confusion reigned. Most of the reporters in the press box were certain that five downs had occurred, and nearly every green-clad spectator agreed. Word of the controversy quickly reached the ears of Cornell President Edmund Ezra Day and athletic director Jim Lynah 1905. But the scoreboard—always the final word—read 7-3. Never had a college football game’s outcome been determined by a decision beyond the field of play.

Only a month earlier, Columbia had scored a game-winning touchdown against Georgia on what film later revealed to be an illegal forward lateral. Two weeks before that, Ohio State had beaten Purdue when a game-winning field goal was kicked by a player who should have been disqualified as an illegal substitute. Neither final score had even been seriously debated. As the Daily Sun had opined after that Columbia game, “Nothing can be done about it now.”

And now Cornell’s unbeaten streak and national title aspirations were on the line. The Big Red players debated the situation on the train home to Ithaca—and they were hardly inclined to forfeit the win. “On that ride back there were all sorts of frenzied versions of what had happened,” then-assistant athletic director Bob Kane ’34 wrote in Good Sports, his history of Cornell athletics. Some, including Drahos, believed that offsetting penalties had necessitated a fifth down. Others pointed out that even if the referees had been in error, they had been hired by Dartmouth. Besides, they said, Landsberg’s third-down run should have been ruled a touchdown. In hindsight, they were likely a bunch of twenty-one-year-olds trying to convince themselves they’d won fair and square.

Meanwhile, Day and Lynah huddled together and made a weighty decision. They emerged to release a joint statement: “If the officials in charge of today’s Dartmouth-Cornell game rule after investigation that . . . the winning touchdown was scored on an illegal fifth down, the score of the game . . . will be recorded as Dartmouth 3, Cornell 0.”

I am now convinced beyond a shadow of a doubt,’ Friesell wrote, ‘that I was in error in allowing Cornell possession of the ball.’

On Monday, Friesell sent a special report to Asa Bushnell, commissioner of the Eastern Intercollegiate Football Association. “I am now convinced beyond a shadow of a doubt,” he confessed, “that I was in error in allowing Cornell possession of the ball for the play on which they scored.” He also admitted that his jurisdiction had ceased at the close of the game; he could not correct his mistake. Bushnell announced that his organization did not have the authority to change the score. It was up to Cornell and Dartmouth.

That same morning, Snavely and Kane scrutinized the grainy game footage. “And we looked—and we looked—and we looked,” Kane recalled. “After running the film back and forth many times he turned off the projector, removed his glasses and quietly said, ‘No question, it was a fifth down.’ ” A telegram was sent to Hanover announcing that “Cornell relinquishes claim to the victory and extends congratulations to Dartmouth.”

Kane described breaking the news to the Big Red players as a “melancholy task.” Day—a 1905 Dartmouth grad—told them they were the best team he’d seen in forty years. One rumor, passed down through the decades, holds that Day believed his alma mater would never accept the concession, and that a gentlemanly demurral would be forthcoming. And in fact, every time Finneran told the tale he concluded on a wistful note: “We’re still waiting for that telegram.”

A return telegram did arrive—stating that Dartmouth accepted the victory “and salutes the Cornell team, the honorable and honored opponent of her longest unbroken football rivalry.”

Dartmouth’s newspaper put out a special edition, and hundreds of students marched through Hanover behind a band playing Cornell’s alma mater. In Ithaca, most of the Big Red players felt frustrated and deflated; indeed, they lost to Penn the very next Saturday. But as the Daily Sun put it, “Our record of sportsmanship still stands unscarred.” The national press agreed. The New York Times marveled that “the result probably deprived Cornell of the mythical national championship of the East; yet the Cornell authorities accepted it without a quiver.” The Syracuse Herald-Journal declared that the Big Red “looks bigger than ever.”

Cornell’s concession turned what would likely have been a historical footnote into an iconic event. A win would have been forgotten in months; a defeat has lingered as legend for seventy-five years. As Kane later noted: “No victory or bundles of victories have or will ever bring the glory this loss with honor has.”

Five Downs, Five Facts

Of the eighteen Cornellians who played in the Fifth Down Game, ten are in the Cornell Athletic Hall of Fame.

In the days before point spreads, Cornell was a 15-1 favorite to beat Dartmouth. But bookmakers refused to pay off on a 3-0 Dartmouth win; instead, they stuck with the 7-3 Saturday score.

Within hours of the game’s resolution, Cornell and Dartmouth were invited to replay it in New York to benefit the Infantile Paralysis Fund (now the March of Dimes). Citing an opposition to “postseason” play, Dartmouth declined.

Another mistaken fifth down occurred on October 6, 1990, when Colorado beat Missouri 33-31 with a final-play touchdown. Although the video clearly showed five downs, Colorado coach Bill McCartney declared that “in no way, shape, or form would we forfeit the game.” His team went on to win the national championship.

The only man to officially score in the Fifth Down Game, Dartmouth placekicker Bob Krieger, went on to play for the Philadelphia Eagles. During one of his pro games in 1941, a referee suffered a severely broken leg and never officiated again. It was Red Friesell—who eventually became a welcome face at Dartmouth and Cornell reunions and had a racehorse named after him, dubbed “Fifth Down Red.”

PHOTOs: Dartmouth Archives, provided