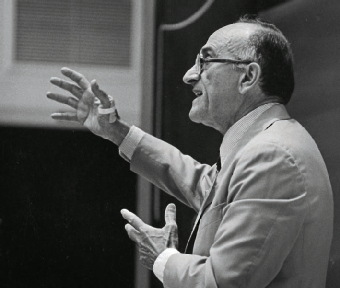

Remembering Alfred Kahn, 1917-2011

Remembering Alfred Kahn, 1917-2011

'If you can't explain what you're doing in plain English, you're probably doing something wrong."

With those words in a celebrated memo written shortly after he became chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Board, Alfred Kahn urged the lawyers and economists on his staff to express themselves more clearly when drafting board rulings and letters for his signature.

"Every time you're tempted to use 'herein' or 'hereinabout' or 'hereinunder' or, similarly, 'therein,' 'thereinabove,' or 'there-inunder,' and the corresponding variants," he continued, "try 'here' or 'there' or 'above' or 'below,' and see if it doesn't make just as much sense."

Kahn, who died in December at the age of ninety-three, was almost alone among his fellow economists in his devotion to clear, parsimonious language. The first impulse of many dismal scientists is instead to ask, "Isn't there some way to make this idea more complicated?"

To be sure, the mathematical formalism that has become the hallmark of the discipline has led to progress on some occasions. But it did nothing to prevent the unclear thinking that helped precipitate the current economic crisis. Macroeconomists, in particular, might do well to consider a variant of Kahn's dictum: "If you can't describe what your model says in plain English without provoking derisive laughter, it probably doesn't say anything of value."

Kahn's devotion to clear language was not just a matter of style. He was also one of the profession's clearest thinkers and a leading authority on the economics of regulation. Many disgruntled air travelers remember him unfavorably as the chief architect of commercial airline industry deregulation. But as he was quick to remind critics, planes now fly with many fewer empty seats than they used to, resulting in much lower average fares, after adjusting for the sharp increases in operating costs that have occurred in the interim.

Much less controversial were his earlier efforts to confront consumers with the real cost of the services provided by regulated companies. A case in point was the rate structure faced by electric utility customers. In 1974, when Kahn became chairman of the New York Public Service Commission, the state agency that regulates public utilities, consumers paid the same rate per kilowatt hour for electricity, no matter what time of day, or in what season, they used it. That rate structure encourages waste, he explained, because electricity is much more expensive to produce and distribute at some times than at others.

Charging the same rate at all times results in utilities serving more of their peak loads with expensive auxiliary generators. If rates during peak demand periods reflected those higher costs, Kahn argued, consumers would face powerful incentives to shift their demands to off-peak periods, thereby saving everyone a lot of money. And, sure enough, in every instance when seasonal and time-of-day rate differentials have been put into effect, electric utilities and their customers have enjoyed enormous cost savings.

Kahn also moved to discontinue the telephone companies' wasteful practice of providing free directory assistance for customers. Directory assistance operators and the equipment they used were costing the companies—and hence ratepayers—a lot of money, even though in most cases they were merely providing numbers that consumers could have easily looked up themselves. Even so, Kahn's proposal to institute a ten-cent charge for each directory-assistance call generated a firestorm of protest. The commission heard solemn testimony that the change would disrupt vital communication networks.

Ever the pragmatist, Kahn amended his proposal by adding a thirty-cent credit on every subscriber's monthly bill, paid for out of the savings made possible by the reduced volume of directory assistance calls. Opposition to the measure vanished immediately. Today, a return to providing that service without charge would seem unthinkable.

While he respected numbers, he loved words and hated to see them misused. "The passive voice is wildly overused in government writing," Kahn's memo to his Civil Aeronautics Board staff continued. "Typically its purpose is to conceal information—one is less likely to be jailed if one says, 'He was hit by a stone,' than if he says, 'I hit him with a stone,'" he wrote, adding that "the active voice is far more forthright, direct, humane."

Though written long before the Internet age, the memo immediately went viral. It was published verbatim in the Washington Post, which also praised it in an accompanying editorial. It generated a marriage proposal from a Boston Globe columnist, who gushed: "Alfred Kahn, I love you. I know you're in your late fifties and are married, but let's run away together." A Singapore newspaper suggested that Mr. Kahn be awarded a Nobel Prize. A Kansas City newspaper urged him to run for president. And, shortly after the memo's appearance, he was appointed to the usage panel of the American Heritage Dictionary, a position he held until his death.

Alfred Kahn was a man of enormous warmth and personal charm. But he was also mindful of the constraints imposed by market forces. When I began teaching at Cornell in 1972, he was dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. A story circulating at the time described an English professor's complaint to him about the high salaries of economics professors. "Perhaps you should consider starting an English consulting firm," he is said to have responded.

I was privileged to serve as Kahn's chief economist at the Civil Aeronautics Board. He was a longtime inspiration to me and countless others. We mourn his passing and feel enormously fortunate to have enjoyed the special glow of his friendship.

— Robert Frank

Robert Frank is the Louis Professor of Management in the Johnson School and the author of such books as Luxury Fever, Falling Behind, and The Economic Naturalist's Field Guide.

From The New York Times, January 8, 2011, © 2011 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited.