At ninety-three, Lee Lorch ’35 is still fighting for what he believes in. His efforts to end segregation and gain rights for women and minorities cost the mathematician an academic career in the United States; he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and fired from university jobs around the country. Now semiretired, he reflects on a lifetime of struggle against injustice.

At ninety-three, Lee Lorch ’35 is still fighting for what he believes in. His efforts to end segregation and gain rights for women and minorities cost the mathematician an academic career in the United States; he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee and fired from university jobs around the country. Now semiretired, he reflects on a lifetime of struggle against injustice.

His civil rights activism and leftist politics cost him a career in American academia. Now in his nineties, mathematician Lee Lorch '35 is still fighting the good fight.

By Brad Herzog

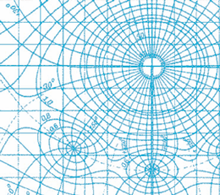

Advanced math isn't often the place where metaphors are mined. A discussion of, say, Lebesgue constants or Fourier analysis—the kinds of concepts with which York University professor emeritus Lee Lorch '35 made his academic mark over the course of more than a half-century— is not going to rouse the poet in most people. But Lorch isn't your typical numbers man; he has long been known for his ability to take a familiar mathematical concept and apply it to new areas of thought. So now, he sits in his two-bedroom apartment overlooking Toronto's Distillery District and employs that skill in an attempt to explain his unwavering efforts to promote racial and gender equality. "Asymptotic expansions," says the ninety-three-year-old mathematician. When he is met by a blank stare, he continues in layman's terms. "Essentially what that means is being able to take a complicated expression and replace it with a simple one after sufficient time has elapsed. Or sufficient distance."

As if to prove a point, he rises from his chair with great effort, grabs a knit cap and down jacket, and motions toward the door. "Come on, I want to show you something." Shuffling behind a wheeled walker, he leads his visitor into the teeth-chattering cold of Canada in mid-March. Along sidewalks, through intersections, testing the patience of late afternoon traffic, he arrives several blocks later at Market Lane Public School.

As if to prove a point, he rises from his chair with great effort, grabs a knit cap and down jacket, and motions toward the door. "Come on, I want to show you something." Shuffling behind a wheeled walker, he leads his visitor into the teeth-chattering cold of Canada in mid-March. Along sidewalks, through intersections, testing the patience of late afternoon traffic, he arrives several blocks later at Market Lane Public School.

A staff member is about to lock up for the day, but her eyes light up at the sight of Lorch. "Well, hello!" she says, as if she has seen his face often. But of course she has. At the entrance to the largely minority school, alongside paintings of Barack Obama and Martin Luther King Jr., is a wall sculpture honoring Lorch. Surrounding a likeness of him are smaller depictions of various aspects of his life—a pi symbol, a picture of Albert Einstein, a photograph of an African American girl surrounded by an angry mob. Beneath it all is Lorch's favorite response when asked about his lifelong efforts on behalf of civil rights—a complex concept made simple: "The question isn't why some people behave decently, it's why too many others don't."

A staff member is about to lock up for the day, but her eyes light up at the sight of Lorch. "Well, hello!" she says, as if she has seen his face often. But of course she has. At the entrance to the largely minority school, alongside paintings of Barack Obama and Martin Luther King Jr., is a wall sculpture honoring Lorch. Surrounding a likeness of him are smaller depictions of various aspects of his life—a pi symbol, a picture of Albert Einstein, a photograph of an African American girl surrounded by an angry mob. Beneath it all is Lorch's favorite response when asked about his lifelong efforts on behalf of civil rights—a complex concept made simple: "The question isn't why some people behave decently, it's why too many others don't."

Above his bed hangs a calendar that he brought home from a trip to the Soviet Union in 1986. Vladimir Lenin stares down from the cover. The scene begs a question: 'Do you still consider yourself a communist?' He doesn't hesitate. 'Yes.'

Sufficient time has elapsed for Lorch to reflect on the distance he has been forced to keep. For a half-century, he has been an American in exile—a man of principle ostracized by academic institutions and persecuted by a country that claims to value freedom above all else.

Lorch's bookshelf, in the home office that doubles as his bedroom, is a reflection of his dichotomous interests. Alongside titles like Maximum Principles in Differential Equations and Elements of Number Theory are The American Inquisition and Cold War on Campus. A shelf is dedicated to the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Above his bed hangs a calendar that he brought home from a trip to the Soviet Union in 1986. Vladimir Lenin stares down from the cover.

The scene begs a question: "Do you still consider yourself a communist?"

He doesn't hesitate. "Yes."

Fifty-five years ago, in the midst of McCarthyism, when he was called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities and asked much the same question, Lorch was more circumspect. This was during his decade-long journey through some of the darkest days of American hypocrisy. Because of his public stand on civil rights, he had already lost faculty positions at two American universities and would meet the same fate at two more. He had been invited for tea with Einstein—who didn't want to talk shop but to discuss the curtailment of academic and political freedom on campuses. He had been, or soon would be, involved in civil rights struggles in places ranging from New York City housing complexes to Tennessee math conferences to Arkansas schools. And now he was essentially being asked if he was a good enough American.

Are you or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party? Lorch responded that he was not currently a member. As for the rest, he kept mum, earning an indictment for contempt of Congress. (He was later acquitted.) "It depends on how technical you want to be," Lorch now says of his reticence. Then he adds with a grin: "And when you're before a body of that sort, you want to be very technical.

It wasn't the lure of communism but rather an abhorrence of fascism that shaped Lorch's world view—as a Jew who came of age during the rise of the Nazi Party. His father was a butcher from Germany, his mother a schoolteacher whose family emigrated from Alsace-Lorraine. They raised four children in New York City. When Hitler came to power in 1933, Lorch's father, the only member of his family who had left Germany, maneuvered to save as many people as possible, bringing over anyone who could claim to be a relative, accurately or not. In fact, he took responsibility for so many people that one day a letter arrived from the U.S. State Department announcing that it wouldn't accept any more affidavits from him. "So that was a big influence," says Lorch, "the rise of fascism and the failure of the so-called democratic West to oppose it in any way."

When World War II arrived, Lorch was determined to do his part. After earning a bachelor's degree in mathematics from Cornell (where he joined anti-fascist organizations and participated in a handful of demonstrations) and a master's from the University of Cincinnati, he accepted a position as a mathematician with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, the precursor to NASA. But while he thought he was contributing to the war effort, he soon discovered that the lag between theoretical studies and practical applications was likely longer than the length of the war. So he resigned from the draft-exempt job to serve in the Army.

But he ran into unexpected obstacles. While working at NACA in Hampton, Virginia, Lorch had refused to eat in the city's segregated restaurants. Instead, he opted for the cafeteria at historically black Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), where he was soon asked to instruct an evening math class, his first teaching job. It raised eyebrows in military intelligence circles. "It had a big influence on my military non-career," he says. "I mean, I was there. I was with an outfit. But I had no real responsibilities." He spent much of his time as an assistant base inspector at Will Rogers Field in Oklahoma.