Held by the Nazis in an underground meat locker in a building called Slaughterhouse Five, Kurt Vonnegut ’44 was one of the few prisoners of war to survive the fire-bombing of Dresden. He never forgot “the carnage unfathomable” visited on the citizens of that city. Little wonder, then, that Vonnegut often observed that “the Dark Ages haven’t ended yet.”

In well over a dozen novels and hundreds of short stories, Vonnegut wrote about the madness of war and about alienation in the modern, machine age. Some readers found him sarcastic, shrill, and simplistic. But when he died in 2007, Vonnegut was acclaimed as a great American writer with a signature style: in unadorned prose, he explored a simple conflict and delivered a solution encased in a surprise ending.

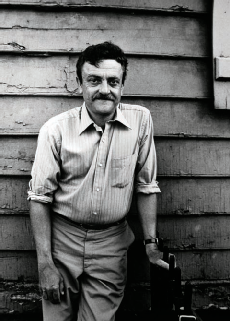

Provided

While Mortals Sleep, from Delacorte Press, is the second collection of previously unpublished short stories by Vonnegut. Written early in his career, they are concerned less with war and corporate malfeasance than with the pursuit of success, happiness, and love. Vintage Vonnegut, for better and worse, they put characters, settings, and stories in the service of moral messages.

At their best, these messages achieve a simple—and powerful—eloquence. In “The Man Without No Kiddlies,” an elderly gentleman, newly arrived in Florida, grows angry when his uneducated ninety-four-year-old bench-mate interrupts his perusal of Shakespeare’s sonnets, prattling on about spleens, sphincters, gallstones, and kidneys. Reminders that human beings are “nothing but buckets of guts,” he exclaims, “make life of the spirit impossible.” He learns he’s wrong, losing a bet and winning a friend by admitting that he’s a “two-kiddley man.”

Vonnegut can be very funny—especially when he’s skewering the super-rich. In “Tango,” he writes that the Latin music that wandered through the ears of young Robert Brewer “found nobody at home under his crew cut, and took command of his long, thin body.” His partner, “a plain, wholesome girl with three million dollars and a low center of gravity, struggled in embarrassment, and then, seeing the fierce look in Robert’s eyes, succumbed.” It “simply wasn’t done” in posh Pisquontuit.

Even when they are funny, however, some of these stories seem dated—and not only because they are set in manufacturing plants like the Montezuma Forge and Foundry Company and the General Household Appliance Company. An awful lot of women in While Mortals Sleep are spinsters or widows, searching, with varying degrees of desperation, for a nice man. And unhappy until they find one.

To be sure, Vonnegut gives the back of his hand to Earl Harrison (in “With His Hand on the Throttle”), a thirty-something road-builder, who plays with model trains instead of spending time with his wife. Women “have got the vote and free access to saloons,” Earl exclaims. “What do they want now—to enter the men’s shot put?” He gets his come-uppance, but the oh-so-Fifties moral of the story seems to be that wives should be more than content if they get common courtesy and a bit more attention from their hubbies.

Dave Eggers, the editor of this collection, writes that the literature of moral instruction—at one time “popular, if not dominant”—has become unfashionable. It’s easy to see why. Some of Vonnegut’s lessons—that wealthy people were happier when they had nothing; that we often ignore the real meaning of Christmas— seem trite or untrue.

But, then again, in an age of relativism, cynicism, and self-absorption, we may well need sentimental, self-evident truths, and reminders that “love and friendship and doing good really are the big things.” Especially when they come, as they often do in While Mortals Sleep, in artful, mordantly witty tales.

— Glenn Altschuler

Glenn Altschuler, PhD ’76, is the Litwin Professor of American Studies, dean of the School of Continuing Education and Summer Studies, and vice president for university relations.

From the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 20, 2011. © 2011. All rights reserved. Used by permission.