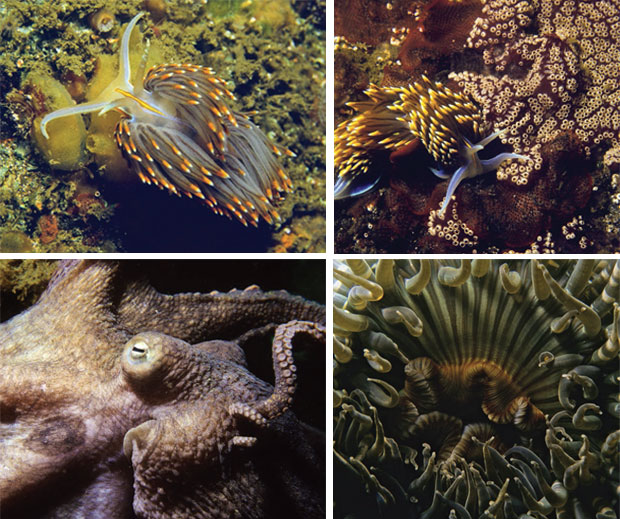

Crystal clear: Blaschka specimens of (from top) the nudibranch Embletonia pallida, the squid Rossia macrosoma, and the sea cucumber Synapta fasciata

What the hell is a nudibranch doing in the Johnson Art Museum?”

David Brown ’83 asked himself that very question one day a few years ago. After more than two decades at sea as an environmental videographer—including work for the legendary Jacques Cousteau—Brown had taken a part-time photography gig on campus, capturing high-resolution images to digitize the museum’s collection. He was walking through a gallery when he noticed the small marine creature, commonly known as a sea slug, in a display case. But it wasn’t a preserved specimen; the extraordinarily lifelike object was made of glass. And it was beautiful.

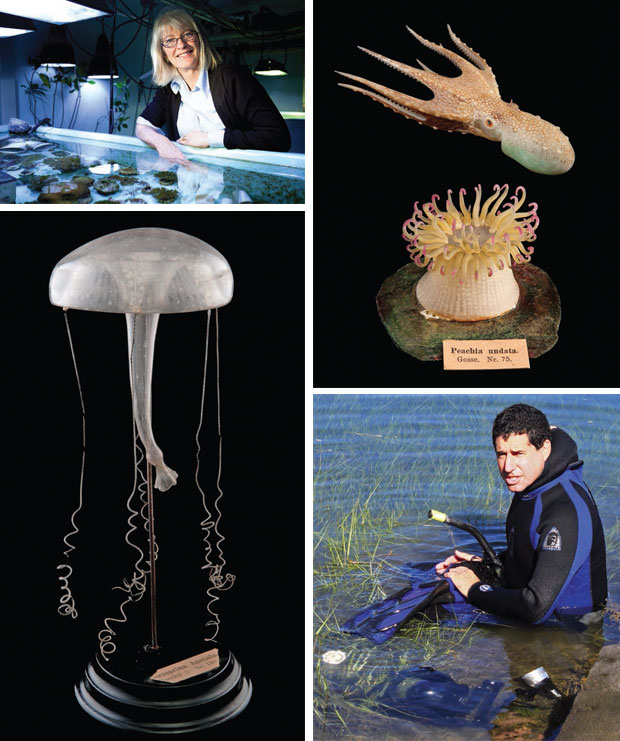

Big blue: Drew Harvell on a research trip to Hawaii; a camouflaged octopus can be seen in the lower left corner.DAVID BROWN

The former history major had stumbled upon the Cornell Collection of Blaschka Invertebrate Models—or, rather, the handful of pieces on display at the Johnson. Curious, he dug deeper. He learned that in 1885, Andrew Dickson White had purchased some 570 of the specimens from the famed Dresden glassmakers—anemones to jellyfish, squid to sea cucumbers—to be used as teaching tools in marine biology. “A hundred and sixty years ago, there was really no way to bring these into a classroom,” says Brown, standing in the Corson Hall atrium that houses dozens of the exquisitely fragile, intricately detailed models in three display cases. “They’d just turn to mush, because they’re mostly water. There was no way to properly preserve them.”

But when technology offered other ways—like underwater photography—to expose students to the creatures, the glass specimens fell by the wayside. As the legend goes, the late chemical ecologist Tom Eisner, then a young faculty member, came across the Blaschka collection in storage in the early Sixties. He picked the lock on their dusty case with a paperclip, found the models faded and broken—and launched an effort to save them that’s still ongoing. Two decades ago the cause was taken up by marine biologist Drew Harvell, now the collection’s curator. “In some ways they’re even more important now, because they’re a time capsule of biodiversity from 160 years ago,” says Harvell, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, an ardent conservationist, and the associate director for environment at Cornell’s Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future. “They’re also important as a teaching tool because some of them are quite rare animals—things I’ve never seen before, and I’ve been studying invertebrates my whole life.”

BROWN

Now, Harvell and Brown are teaming up to make a documentary about the Blaschka models, the nineteenth-century artisans who made them, and the habitats where the creatures originally flourished. Entitled Fragile Legacy, it will tell a series of interwoven tales comprising art, biology, history, and man’s effect on the oceans. It includes the collection’s genesis story: how in 1853 master glassmaker Leopold Blaschka was sailing from Europe to the Americas when, halted by calm winds, he encountered some remarkable marine life. “Most people would go below decks and play poker, but he spent a lot of the time looking over the rail, and he’d see these things pulsing by,” Brown says of the invertebrates. “He became enchanted with how glasslike they were and decided to try to make them.” Blaschka began by painting intricate, anatomically exact watercolors of the creatures; those images (now in the archives of the Corning Museum of Glass, an hour southwest of Ithaca) became the basis for the models, created with a combination of glassblowing and lampworking. “But exactly how he, and eventually his son, Rudolph, made the nuances of this glass has been lost,” Brown says. “They were a father-son team, and they didn’t have an apprentice, so the exact method by which these things were created is not fully understood.”

Handle with care: A Blaschka siphonophore, Apolemia uvaria

For Brown and Harvell, that deficit echoes a wider one: the devastation of the oceans through pollution, overfishing, acidification, rising temperatures, and other manmade ills. “If you think about it, the loss of that knowledge runs parallel to the loss of genetic information every time a species goes out of existence,” Brown observes. “Here they were at the start of the Industrial Revolution, capturing these incredible creatures that because of the Industrial Revolution would become threatened as the chemistry of the ocean changed. So the film will pair the fragility of the organisms in their habitat with the fragility of the glass.” Then there’s the irony that if Blaschka had taken his ocean voyage through less environmentally friendly means, the masterpieces might never have been conceived in the first place. “Sailing was in the process of giving way to fossil fuel propulsion,” Brown notes. “He happened to be on a sailing vessel, or he wouldn’t have been stopped; when you’re traveling by fossil fuel, you just plow through everything and don’t see much. And as sailing gave way to fossil fuel, the chemistry of the ocean changed. So that’s another story thread running through it.”

Wet and dry: (Clockwise from bottom) Brown working on a conservation project in Maine; the Blaschka jellyfish Carmarina hastata; Harvell on land; the Blaschka Octopus cocco,and sea anemone Peachia undata

So far, Brown and Harvell have taken the first of what’s planned to be a half-dozen research trips for the film; they went to Hawaii in early 2013, capturing footage of Harvell diving with a common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) that’s an exact match to the Blaschka model, which is currently in fragments awaiting repair. Brown will chronicle that restoration—by a Corning glassworker named Elizabeth Brill, who has been working on the collection for two decades—and will ultimately use computer graphics to morph the model into the live creature filmed with Harvell, creating a bridge between art and life. “I want people to be enraptured by these creatures and to understand that they’re absolutely critical to the health of the ocean, and consequently to our health,” Brown says. “I’ve been in marine documentary for twenty or thirty years, and everyone wants to see sharks and whales—the big stuff. But these guys are just as important, and in some cases more so. They all have roles to play, and they’re getting flattened along with everything else.”

Mollusc Melibe australis

In early May, the New York Times published an essay in which Harvell chronicled the trip to Hawaii’s Mauna Lani Reef, where the filmmakers encountered a variety of species, including another cephalopod known as Octopus ornatus. “It sat stolidly in the light of the camera, thirty feet below the surface, unfazed by the attention,” Harvell wrote. “I reached out a finger and it touched me with its suctioned tentacles. When it scuttled in the other direction, I herded it between my cupped hands as it watched me attentively with searching golden eyes. As if levitating, it smoothly lifted off and tried to jet over my head, but slowly enough that I could catch it gently in midair—like handling a large bird, albeit one with eight sticky tentacles.” The online version of the story included a multimedia element that allowed visitors to rotate the glass models as well as view the real animals in their natural habitat. (Brown came up with an innovative solution for the Blaschka photo shoot: after unsuccessfully searching for a Lazy Susan that would turn perfectly smoothly, he put the models on a gerbil wheel laid horizontally.)

Future research trips are planned to the Mediterranean, to Indonesia, and to Cornell’s Shoals Marine Lab off the coast of Maine, where they’ll film Atlantic species. Brown also hopes to shoot on a sailing vessel in the open ocean, to capture a sense of what Leopold Blaschka first experienced more than a century and a half ago. “I love these critters,” Harvell says. “This is my passion. Just to go find them and see them alive is exciting—and filming them is fun, because we get to see them in ways that we normally wouldn’t.” The filmmakers have received enough grant money to get started on the project, but not enough to complete it, so they’re currently soliciting donors; similarly, progress on restoring the models has been slow due to limited funding, with about 220 of the pieces completed. (In addition to Corson Hall and the Johnson Museum, Mann Library has a Blaschka display, and many can be viewed online at blaschkagallery. mannlib.cornell.edu.) “The marine biodiversity recreated by the Blaschkas is a phantasmagorical view of life in the oceans,” Harvell wrote in the Times. “For they were artists as well as keen natural historians, with an eye for the forms that would enchant in glass and that were too rare or fragile to be seen readily.”

Brown aims to film Fragile Legacy in “4-K”—about four times the resolution of current high definition—to capture the glass models, the real-life creatures, and their habitats in vivid detail. He envisions a series of modules, each focusing on a different category of invertebrates. He’ll also describe the restoration process and tell the story of the Blaschkas, arguably best known today as the makers of Harvard’s collection of more than 3,000 botanically exact glass flowers. (“Harvard stole them away from the marine invertebrates to do the lousy flowers,” Brown jokes. “I don’t know why.”) The modules could be viewed as individual webisodes or joined to form a feature-length film, to be screened in venues like museums and aquariums. It could also air on PBS—where, Brown imagines, the subject matter could attract both the “Nature” and “Masterpiece” crowds. “I’m finding art to be an unusual vehicle,” Harvell muses. “As a scientist, I didn’t understand how powerful art can be in motivating and exciting people. Some people aren’t that interested in marine invertebrates—but then they look at one of these squid or a jellyfish and they’re like, ‘Wow, are you telling me there’s something that looks like this that’s alive in the ocean? What does it eat? What does it do?’ Somehow, seeing the art awakens an interest in the living creatures.”