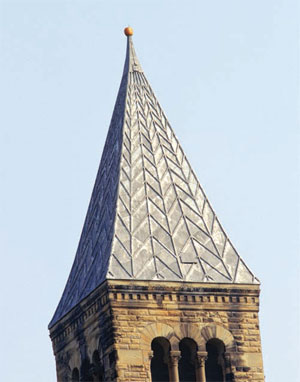

The mysterious clocktower pumpkin, which appeared around Halloween in 1997, became a safety hazard as it threatened to topple.

On a frigid night in January, Corey Earle ’07 is working a mostly alumni crowd at Ithaca’s Kendal retirement community, regaling listeners with Cornell’s rich history of pranks, shenanigans, and practical jokes. The associate director for student and young alumni programs in the Office of Alumni Affairs, Earle is an unofficial University historian, the anecdotal crown prince of Cornell lore.

He opens with the tale of a student in the 1870s who pretended to be a traveling lecturer and expert on subjects, like France, that he knew nothing about. The Halloween hijinks in Cascadilla Hall, Cornell’s first dorm, included a celebrated gag in which upperclassmen “sold” radiators to freshmen. Other drollery, like soaping trolley tracks and destroying fences, strained town-gown relations. By 1884, enough was enough. “In regards to any attempt to make yourself immortal or famous by some college prank, remember you are here as men,” founding President A. D. White harrumphed. “As long as you consider yourself as such, you will be so considered.”

White’s opprobrium put a temporary kibosh on burning down outhouses and other hijinks, Earle says. But it wasn’t long before those pesky kids were at it again. “Pranks have been part of Cornell since the very start,” says Earle, a third-generation Cornellian. “As long as there are students, there will be mischief and shenanigans.”

Earle’s talk, which he debuted at Kendal, runs the better part of an hour. Among its merry pranksters is Daisy Farrand, wife of Cornell’s fourth president, who in 1921 enlisted a senior to give two lectures posing as a pupil of Sigmund Freud. The stunt made national headlines.

Cornellia, the frequently abducted bovine.

Arguably the University’s most prolific practical jokester was Hugh Troy ’26, whose elaborate japes included phony class photo shoots outside Sibley Hall—unsuspecting students got drenched with water—and the mysterious “rhinoceros” footprints that led to a hole in frozen Beebe Lake. Kicked out senior year for scandalous headlines in the Daily Sun (“President Breaks Wind Over New Aeronautics Hall”), he refused an invitation to return.

Then there was the time that Kurt Vonnegut ’44 walked into an exam for a class he’d never attended, tore his bluebook to pieces, and tossed the test in the face of an astonished proctor. Or when, in 1954, a daredevil named Roberto Alvarez allegedly went over Taughannock Falls in a barrel. (There was a barrel, but no Roberto.) Beloved vet professor F. H. Fox ’45, himself a famed prankster in his day, still sees his hatred of birthdays mocked annually when students spray-paint his age—now ninety—on an old railroad trestle outside of town. Curtis Reis ’56, a.k.a. Narby Krimsnatch, returns to campus occasionally to poke fun at the stiff-upper-lip crowd with goofy getups and faux-foreign addresses. The Dairy Store’s fiberglass mascot, Cornellia, has been cow-napped so many times she’s now kept under lock and key.

Earle says that a gentle jokester, like a good doctor, “causes no permanent damage.” But not all pranks have proven benign. In 1894, a stunt involving chlorine gas killed a cook, sickened many freshmen, and got Cornell cited in law books after sophomores pled the Fifth. In 1968, a Playboy bunny insignia burned into Schoellkopf Field with toxic chemicals sent football players to the hospital with rashes and burns.

Earle winds up his act with the great pumpkin prank of 1997, another Cornell caper that drew national notice. The perpetrators remain unknown to this day, though a decade ago their alleged method was anonymously leaked to the media. It involved a disabled door lock, some mountain climbing gear, and nerves of steel.