The sundial on the Engineering Quad isn’t just a beloved campus fixture—it’s one of the most accurate instruments of its kind on the planet. Assuming that the sun is shining, users need only turn a dial on the six-foot-wide, 650-pound sundial’s granite base to indicate that day’s date, and they can see the correct time to the minute, twelve hours a day, all year round.

The sundial on the Engineering quad.Lisa Banlaki Frank

Installed in 1980, the instrument is named in memory of Joseph Pew Jr. 1908—an industrialist, Engineering alum, and prominent Cornell benefactor who’s also the namesake of the Engineering Quad. Its creation was the brainchild of Pew’s widow, who thought a sundial would be a fitting homage to her late husband, given his long association with the college. But when the University drew up its initial proposal for the device, it met with vocal resistance from a prominent figure: President Emeritus Dale Corson.

Corson—a physicist who had previously served as Engineering dean—had been a sundial aficionado since his days studying celestial navigation in the U.S. Army Air Corps. He strongly objected to the project’s original design, which he dismissed as a “garden ornament.” As Corson recalled to CAM in 2007: “I had so much criticism of it that they said, ‘Well, you do it.’ ” So he teamed up with Richard Phelan, MS ’50, then a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, to reimagine the instrument.

Jason Koski/UREL

How does the sundial they ultimately created tell time so accurately and reliably? It works like this: Along one of its inner curves is a series of lines, one for each minute from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m.; when the sun shines, a thin cable casts a shadow indicating the time. A system of gears, cables, and pulleys within the granite base is connected to the sundial’s heart: a grooved metal disk called the cam. Its careful design incorporates such factors as Ithaca’s latitude and longitude, the speed at which the sun travels across the sky, the tilt of Earth’s axis, and the irregularity of its orbit around the sun. All that precise engineering is built into the device—meaning that no technical know-how is needed to use it. “In fact,” as a 2009 book on Corson notes, “it was intended to be what Phelan [called] an ‘audience-participation sculpture’—the first person who happens along in the morning sets the date.”

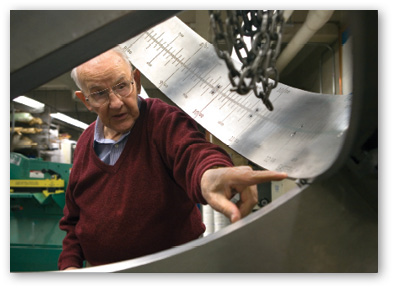

Corson during its refurbishment.Jason Koski/UREL

Placement was also key: as the book points out, the sundial’s location was determined not by aesthetics, but by such practicalities as maximum year-round sunlight and the stability of the underlying ground. In 2006, the timepiece got even more accurate when Corson and Rodney Bowman, a scientific instrument maker on campus, replaced the cam with an upgraded version, crafted in the Clark Hall machine shop. (Phelan had retired in 1988.) “Dale was about ninety years old at the time,” recalls Stanley Carpenter, who managed the machine shop until his retirement in 2009. “But working on this project, he was as enthusiastic as a freshman.” The original cam had rusted over the previous twenty-six years—so the pair made the replacement out of corrosion-resistant stainless steel. “Considering the weather in Ithaca,” says Carpenter, “this was a huge improvement.”