To avoid being dismissed as a “hippie,” Bruce Dancis ’69 donned a coat and tie to destroy his draft card.

Late in 1966, Bruce Dancis ’69 tore up his draft card in front of Olin Hall. Several hundred people—friends, foes, and FBI informants—observed the action, which would lead to a federal indictment, conviction on a charge of draft card mutilation, and a prison term of nineteen months. Dancis was a leader of Cornell’s chapter of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and an outspoken critic of the Selective Service System, which was drafting thousands of men for military service. Many of them were sent to fight—and die—in Vietnam.

Dancis grew up in the Bronx, the child of socialist parents. By the time he came to Cornell he was already an activist, having taken part in civil rights protests as a teenager. “Being an observer and later a participant in civil rights demonstrations really affected me,” says Dancis. “That was a model—seeing that civil disobedience for a righteous cause can get a lot of support.” When he turned eighteen, Dancis registered for the draft but refused a student deferment. “I thought it was unfair,” he says.

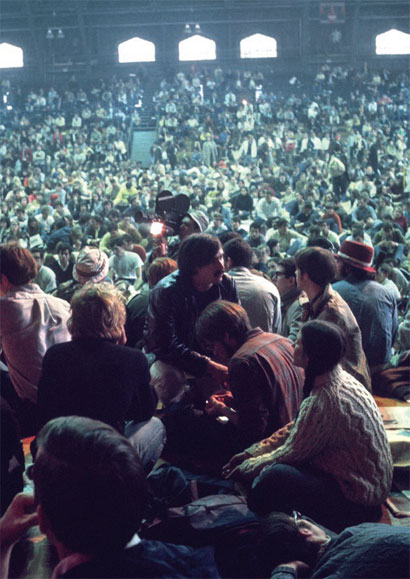

On campus, Dancis was a prominent figure in protests against the Vietnam War and in the actions surrounding the Straight takeover in 1969, including the famous Barton Hall Community. Less than a month after that landmark event, he went to federal prison. After his release, Dancis continued his education at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Stanford. He went on to become a journalist, working at newspapers and magazines until his retirement five years ago.

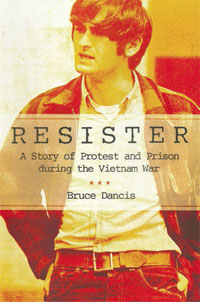

Dancis tells the story of his draft protests and imprisonment in Resister, a memoir just published by Cornell University Press. Both personal and political, his account offers an honest and unflinching look at one of the most turbulent times in the history of the University and the nation. Writing the book, he says, stirred some old memories—and he’s sure that will be true for his readers as well. “For some, the wounds of Vietnam haven’t healed. It’s an old argument that’s still going on, so it will be interesting to see how people respond to what I’ve written.”

Hell No, He Won’t Go

An excerpt from Resister captures a crucial moment in the antiwar movement

By Bruce Dancis

Bruce Dancis today

In the fall of 1966, many of us in Cornell SDS were open to exploring different tactics and strategies to build opposition to President Johnson’s war policy. We were willing to join in coalitions with other groups to expand the antiwar movement.

A new group called Students for a Constructive Foreign Policy was formed by liberal student-government types to go to the freshman dorms to talk to students about the war. It was the kind of grassroots organizing that I, as SDS president, should have been promoting, but had not. Nevertheless, many SDS members joined SFCFP in going to the dorms.

Also active on campus were the Young Friends, a Quaker-affiliated group that organized a weeklong fast for peace with the support of many of Cornell’s chaplains. Although I wasn’t too familiar with the Quaker tenet of “witnessing,” I decided to take part in the fast. I consumed nothing but water for seven days, spending part of each evening meeting with other fasters to discuss peace and maintain our morale.

At around the same time I also persuaded my apartment-mates to join me in a new nationwide protest of Congress’s adoption of an increase in federal taxes on telephone bills (from 3 percent to 10 percent) to provide revenue to pay for the war in Vietnam.

Unfortunately, neither the fast, the telephone tax protest, nor any other activity against the war swayed the Johnson Administration. By the end of the year, the number of American troops in Vietnam had reached nearly 400,000. More than 6,000 U.S. soldiers had already been killed in Vietnam.

Dancis (center) leads a group of protestors to Barton Hall, where they’d confront Marine Corps recruiters.

Like many others in the antiwar movement, I was growing frustrated with our lack of effectiveness. I felt this even within our draft resistance union. By late November, our ranks were up to about twenty. We were all committed to refusing to fight in Vietnam, but remained divided and unclear about what to do next. In part, this reflected our political diversity. While some of us came out of SDS, others were not part of any group. We had Christian pacifists, anarchists (like Matty Goodman ’67, a non-registrant and the son of the radical social critic Paul Goodman), and some who defied ideological categories. Most of the group was still opposed to actions that would almost certainly result in going to prison.

But this attitude started to change after we met with Ralph DiGia of the War Resisters League. Ralph had spent time in federal prison during World War II. Our conversations with him convinced many of us we could survive several years in prison. For me, these discussions helped remove the only thing keeping me from severing my ties with Selective Service—fear of the repercussions.

By the beginning of December, my draft card was (figuratively) burning a hole in my pocket, and I couldn’t stand remaining complicit with the system that was integral to perpetuating a war I abhorred. I was also concerned that the momentum of the antiwar movement had stalled. I felt people needed to take stronger, riskier actions both to keep the pressure on the Johnson Administration and to increase the seriousness of the movement itself. I hoped my own action would, in a small way, help build a larger and more committed antiwar movement. I was willing to act alone, but hoped that others would be joining me in the not-too-distant future.

That’s when I decided to destroy my draft card and cut my ties to the Selective Service System. When I told my fellow draft resistance union members about my decision, some were concerned that I had not sufficiently explored the consequences of such an action. But most recognized that my choice was based on months of deliberation and a clear understanding of what could happen to me. Although none of the others was ready to join me in openly breaking with the draft system, we decided as a group to make a public declaration of our opposition to military service.

For me, the only questions remaining were just what kind of action should I take? And when should I do it?

Having made my decision, I didn’t want to wait too long to carry it out. As I talked to my closest friends, [assistant professor of mathematics] Bob Greenblatt suggested an upcoming meeting in which the University faculty was to vote on the proposals offered by a faculty committee on Selective Service. The faculty meeting was scheduled for Wednesday, December 14.

I called my parents to tell them of my intentions, and they urged me to wait until after the upcoming Christmas vacation so we could discuss it further. I said that my mind was made up. My parents undoubtedly knew how determined, and stubborn, I was, but they nevertheless immediately drove up to Ithaca to make one final attempt to dissuade me. I felt bad that I was putting my folks through such stress and worry, but I refused to change my mind. My parents left Ithaca troubled and anguished, but I knew they understood how hard I had thought about this. I hoped they would be proud of me and would stand with me.

It was purely a coincidence that Wednesday, December 14, 1966, began with our antidraft union’s statement appearing in the Daily Sun. Signed by twenty-one men, the ad read in large letters: “WE WON’T GO.” Beneath that headline, it said, “The undersigned men of draft age will not serve in the U.S. military. We encourage others to do the same.” Our statement closed with, “People needing help with the draft, and anyone interested in signing this statement, please contact one of the above.”

Statements such as ours, which were beginning to appear in campus newspapers around the country, not only represented the first time significant numbers of draft-age men pledged to refuse to fight in Vietnam, but also suggested that we would try to build a larger movement of resistance. At the time, even such public declarations were considered potential targets for federal prosecution or reprisals by Selective Service.

The publication of our statement, coupled with the news that Pat Griffith was accompanying three other antiwar women on an illegal trip to North Vietnam to investigate civilian casualties and other concerns, made December 14 a particularly important date for the Ithaca antiwar movement. Later that day, I would make my own contribution.

SPOTLIGHT: IT’S UP TO HIM, AND YOU, AND ME

DECEMBER 14, 1966

Rebels don’t usually “dress up” when they openly defy their government. But as I stood in front of the chemical engineering building at Cornell late in the afternoon on a cool mid-December day, about to make my own, personal declaration of independence and take a step that would affect the rest of my life, I was clad in a blue blazer, tie, and white button-down shirt. I chose to wear such clothes not to pretend I was someone I was not, but in an attempt to avoid being marginalized as a “beatnik” or “hippie.”

A crowd of about 300 people had gathered near the front steps of Olin Hall, where I planned to speak. Most were friends and supporters, who knew why I was there, but a vocal group of hostile engineering students was also present, no doubt curious as to why all these strange people had arrived on their turf. Inside the building, the University faculty was voting to support the proposals of the faculty committee on Selective Service, which perpetuated the existing policies of the Cornell administration. The local media were also in attendance, having been contacted by our draft resistance union.

Earlier in the day, the Albany bureau of the FBI had sent a text marked “Urgent” to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. After identifying me as a Cornell student, president of the Cornell SDS chapter, and an “active member of anti-draft group,” it stated, “Info received from source that subject intended to burn his draft card at Four PM this date prior to meeting of Cornell faculty. . . . After publicly burning card, subject intended to mail remanents [sic] to his local draft board. Reports of alleged burning have been made on local radio stations and have caused considerable local interest. Bureau will be advised subsequent developments.”

Scheduling my action for 4 p.m. made sense logistically, as it would coincide with the faculty meeting. But having to wait until the late afternoon was very difficult, as the hours passed at an agonizingly slow pace. I spent some time going over the statement I intended to read and then mail to my draft board in the Bronx; I also passed the time just hanging out with my pal Peter Agree ’69, MAT ’71.

I had no second thoughts about my plan. I knew I was about to take my life into territory I could barely imagine and for which no map existed, yet I was never consumed by fear. Whatever stress I was feeling seemed manageable, no worse than the butterflies I used to get before a track or cross-country race. Then again, I was chain-smoking unfiltered Lucky Strikes, and Pete remembers me shaking a bit in my cold, drafty apartment, so perhaps I’m not the best judge as to the state of my nerves on that day.

To keep my spirits up I listened over and over to recordings of the song “Universal Soldier”—both Buffy Sainte-Marie’s original version and Donovan’s cover. Nothing better captured my determination to stand up for what I believed in than the song’s eloquent plea for people to take personal responsibility.

April 22, 1969: Dancis was one of the leaders of the Barton hall Community in the aftermath of the Straight takeover

I was also inspired by the eloquent words of Mario Savio, one of the leaders of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement in 1964 and perhaps the greatest orator to come out of the student New Left. Although I was still in high school and not paying too much attention to the events in Berkeley in December 1964 when Savio spoke, his ringing call for civil disobedience had become legendary in the movement and was widely reprinted. His words, which were also relevant to the draft, moved and encouraged me:

There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can’t even passively. And you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop. And you’ve got to indicate to the people who run it, the people who own it, that unless you’re free, the machine will be prevented from working at all.

A Speech and an Action

When I arrived outside Olin Hall, my supporters had set up a loudspeaker and a microphone. I prefaced my remarks by stating I was acting as an individual and not as a member of any organization I belonged to at Cornell. (Neither Cornell SDS, of which I was president, nor the Ithaca draft resistance group had yet taken official positions in support of draft resistance actions.) I then started reading my statement to Selective Service Local Board No. 26, which explained my decision to refuse a student deferment and summarized the actions I had taken thus far against the war. I said I had not done enough.

The crowd was generally somber and supportive, though some of the engineering students heckled me. One even yelled out, “Three cheers for Dow!”—a reference to the Dow Chemical Company, which had become a frequent target for antiwar protests because it manufactured napalm for use in Vietnam. My speech lacked Sainte-Marie’s grace and Savio’s imagery, but it accurately expressed what I was feeling:

The genocide committed by Nazi Germany is condemned by all decent human beings. We say that the German people should have said no to concentration camps, and to the murder of six million Jews. Likewise, we Americans must say no to napalm, to pacification programs, and to the mass murder of the Vietnamese people. I must say no to the draft.

By cooperating with the draft I am forced to work along with an organization that is contrary to any democratic principles. With the draft system, the most basic human right—the right to live—is taken away from a person. Aside from the horribleness of forcing a person to kill, conscription forces a human being to disrupt his life and act at the whim of another human being.

The destruction of the American conscience, the destruction of thousands of people, and the destruction of our universities is being caused by the United States government, its Selective Service System, and by our acquiescence. I cannot aid in that destruction. I must live by the principles that I consider ethical and good. For these reasons I must declare my noncooperation with the Selective Service System and sever all ties with it.

Yours for peace and freedom,

Bruce Dancis

I then took my draft card out of my pocket, tore it into four pieces, placed it in an envelope that had been stamped and addressed to my draft board, and sealed it. I said a few more words about Vietnam, racism, and the need for change, then walked over to a nearby mailbox and deposited the envelope.

I thought I would immediately be arrested. (From my FBI file, it appears that at least six FBI agents and/or informers witnessed my action.) But according to the Sun’s report, a local FBI agent stated it was not the federal government’s policy to have the FBI step in when a person mutilated his draft card.

The Syracuse Post-Standard quoted a local FBI official as saying, “We are cognizant of the facts and are conducting an investigation. . . . The facts will be presented to the U.S. attorney who will then decide whether to prosecute.” The story also cited a second FBI official who said my action was the first in upstate New York “involving deliberate draft card mutilation, a violation of the Selective Service Law.” (According to the book SDS by Kirkpatrick Sale ’58, I was the first SDS member to publicly destroy his draft card.)

The Syracuse newspaper story, written by staff correspondent Jon Levy, was a strange mixture of dubious and mistaken information. Citing “informed sources in the Cornell administration,” Levy wrote that I was “a devout pacifist” [true] who was “being manipulated by other persons within the organization to which he belongs” [utterly ridiculous]. The story also conveniently listed my home address, which may have enabled some friendly types to send me hate mail. One unsigned note called me a “chicken livered coward” and “a stinking Jew!”

Some of my friends were surprised that I decided to tear up my draft card rather than burn it. One of my reasons was practical: What if I lit a match and the wind blew it out? I didn’t want to be nervously fumbling with matches or a cigarette lighter. But more important, since I was seeking a confrontation with the draft system, I felt that by sending my board the actual pieces of my draft card I was making a clear and unambiguous statement: I will no longer obey your laws that support evil and destructive policies.

I knew I was forcing the issue and would undoubtedly go to prison for my actions. But resistance had to start sometime, so why not now? And if it had to start with one person taking a stand and saying no, why shouldn’t that person be me?

A College Dropout

So what do you do on the day after you’ve committed a felony that could get you a prison term of five years and a fine of $10,000? You return to class in a halfhearted and ultimately futile attempt to salvage an academic semester that had begun with divided attention and was concluding with total neglect. I had stopped going to my classes during the week prior to tearing up my draft card, and now, over the last weeks of the fall semester (which continued through the end of January 1967), I tried to cram in a semester’s worth of work. But even my last-minute attempts to catch up were halfhearted, as my action had taken me to a place where school didn’t seem very important.

By the end of January I had decided to take a leave of absence from Cornell to work full-time in the antiwar movement. I wanted to devote my attention to the forthcoming Spring Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam, scheduled for both New York City and San Francisco on April 15, 1967. Bob Greenblatt had already taken a leave from his faculty duties to serve as a co-chair of the Mobe’s steering committee, and he welcomed my participation in building support for what we hoped would be the largest antiwar demonstration in history. I also wanted to keep working with Cornell SDS and with our antidraft union. The Office, where I was already spending a lot of time in lieu of being a serious student, became my full-time workplace when I wasn’t in New York with Bob.

Even though schoolwork seemed far removed from where I was going, I nevertheless tried to keep my options open. I took an official leave of absence from the ILR school, retaining the possibility of returning to Cornell in September ’67.

This decision did not sit well with my parents, who cut off the monthly stipend they had been sending me for room and board. To them, this was a matter of political principle. They may have loved me, but they did not support my political aims or the aims of the groups I was working with. As my mother put it at the time, “If your movement needs you so much, it should financially support you.” Fortunately, by putting together the small savings I had accumulated, a few bucks here and there from the Office and Bob Greenblatt, and my roommates’ graciousness in letting me pay less rent, I had enough money to get by.

I now took on a new role, as a nonstudent activist. Within a year or so, more and more Cornell students would either drop out or remain in Ithaca after graduation to work for the movement.

Excerpt from Resister: A Story of Protest and Prison during the Vietnam War by Bruce Dancis, published by Cornell University Press. © 2014. All rights reserved.