Cornell scientists' study on gas drilling generates both heat and light

Cornell scientists' study on gas drilling generates both heat and light

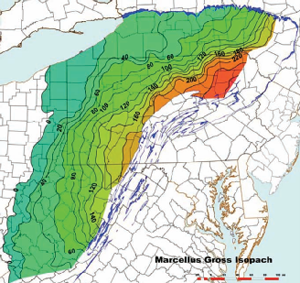

After returning to Cornell in the summer of 2009 from a sabbatical in France, Robert Howarth, the Atkinson Professor of Ecology and Environmental Biology, heard a radio advertisement that caught his attention: a company was touting natural gas extracted from shale as a "green" fuel that did not cause global warming. At the time, much of New York's Southern Tier was in the midst of a leasing frenzy as gas companies were obtaining property rights to drill in the Marcellus Shale, a geologic formation stretching from West Virginia north into the farmland surrounding Ithaca.

An earth system scientist who has researched global warming for nearly thirty-five years, Howarth wondered if any studies could verify that natural gas extracted from shale was an environmentally clean fuel. Finding no scientific basis for the claim, he decided to launch his own study and enlisted the help of two Cornell colleagues: Anthony Ingraffea, an engineering professor, and Renee Santoro '06, a research technician.

Their paper, published in the peer-reviewed journal Climatic Change Letters in April, concluded that natural gas released through unconventional drilling using high-volume hydraulic fracturing ("fracking") causes more global warming than coal. When considered over a twenty-year time period, the paper stated, the greenhouse gas footprint of shale gas is at least 20 percent greater than and possibly more than twice as great as that of coal. Over a 100-year time frame, the greenhouse gas footprint of shale gas is comparable to that of coal. And when compared to gas extracted using conventional drilling, the paper said, methane emissions from shale gas are at least 30 percent higher and perhaps more than twice as high.

"This is widely promoted as a 'green' fuel that's good for the country and an easy way of continuing to live off fossil fuels without having to worry about fossil fuels affecting climate change," says Howarth. "It didn't ring true to me, which is why I went looking for the science [to back up the claim], but didn't find that science."

Natural gas is 95 percent methane, a greenhouse gas that is 105 times more potent in trapping heat than carbon dioxide over a twenty-year time horizon and thirty-three fold more potent over a 100-year time horizon, the study noted. During the lifetime of a shale well that uses unconventional drilling, the study estimates, 3.6 to 7.9 percent of the methane it produces will leak into the atmosphere.

Critics in the gas industry were quick to respond. In fact, they launched an attack on the paper before it was even published, distributing information from an unauthorized (and not final) draft. The industry also marshaled a series of negative blogs and, according to Howarth, took out a Google ad, so reporters searching for "Robert Howarth" would first encounter a list of critiques. Some scientists, including Cornell colleagues Lawrence Cathles and Larry Brown, PhD '76, both professors of earth and atmospheric sciences, also questioned the study's conclusions. Many other scientists praised the study, however, and Howarth is quick to point out that no peer-reviewed journal has published a study that refutes his work.

Much of the criticism focuses on the study's conclusions about a twenty-year time frame, since methane lasts only for ten to twelve years in the atmosphere while carbon dioxide remains for about 100 years. Ingraffea says that it's vital to look at the shorter time period when considering the effects of gas drilling, because of the urgency of avoiding disastrous climate change effects, including the melting of the ice caps. "If your policy is 'What can we do to slow climate change?' why wait 100 years if you're trying to have an effect now, so that we do not have a climate tipping point, which scientists are worried about," says Ingraffea, the Baum Professor of Engineering. Current estimates show that the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is 390 parts per million and is increasing at roughly two parts per million a year, Ingraffea says. If, as many scientists believe, the point of irreversible climate change will be reached when there are 450 parts per million, the window of opportunity to have any impact on global warming could be just thirty years.

Subsequent to the publication of the Howarth, Santoro, and Ingraffea study, the United Nations issued a report again stressing the urgency of addressing climate change and emphasizing the need to focus more on methane and other short-lived greenhouse gases. Then, in June, Governor Andrew Cuomo's administration issued draft rules that would allow fracking in most of the Marcellus Shale in New York State, with some exceptions including land near the New York City and Syracuse watersheds.

Because the Marcellus Shale gas is trapped beneath layers of rock, millions of gallons of water combined with sand and chemicals would be blasted underground to fracture the rock, releasing the gas for extraction. The Howarth study argues that methane escapes into the atmosphere during the first two phases of this procedure: flow-back, when the water injected into the shale returns to the surface, and drill-out, when plugs used to separate fracturing stages are removed to release the gas. In conventional wells, which rely mostly on vertical drilling and smaller amounts of water, the methane leaks during those stages are far lower in volume.

Howarth and Ingraffea oppose high-volume hydraulic fracturing in the Marcellus Shale because of the negative impact it could have on global warming. "Our conclusion is that this could be pretty disastrous for climate change, so I do not think it is wise to proceed," asserts Howarth. Instead of trying to convince the gas industry to reduce the amount of methane seepage, which Howarth says is unlikely because it would be too costly, he believes the country should move toward adopting renewable energy sources, such as solar, wind, and geothermal. "We can't go on using fossil fuels," he says. "Sooner or later, we need to convert to a sustainable energy system. The technology is mostly there now. The faster we move to that, the better."

— Sherrie Negrea