Wayne Beyer mumbled the prayer every day, confused and alarmed. Growing up in Queens, Beyer was raised by Conservative Jewish parents who opted to send their oldest child to a yeshiva, an Orthodox day school. There, Beyer stood with the rest of the boys and recited a morning blessing: "Blessed art thou, O Lord our God, who has not made me a woman." It was, Beyer recalls, "like swallowing crushed glass." Wayne's earliest memory, starting around the age of six, was simply this: "I am not a boy." Forget wanting to be Mickey Mantle; he wanted to look like the Breck girl on TV.

While Beyer's mother, Selma, was pregnant in 1951, she had been prescribed DES, a synthetic form of estrogen widely used to prevent miscarriages. The drug was banned in 1971, largely because it was linked to vaginal cancer, but Beyer is certain that it also caused intersex conditions. DES, she says, was "the worst drug disaster in American history."

Most news accounts describe Beyer as being born with "conflicting genitalia." The reality is that Beyer had fully functioning male genitalia and elements of a female reproductive system— specifically, an enlarged prostatic utricle, which is the male version of the uterus. But Beyer's "brain sex" was nowhere near as ambiguous. "People ask me, 'What was it like being a man, and what is it like now being a woman?' And I say, 'I don't know. I never felt like a man. I had a female brain. I could tell you what it was like pretending to be a man,' " she says. "Transitioning is a choice, but who you are is not a choice."

As a pre-teen, Beyer would occasionally try on his mother's clothing, even leaving it scattered around the house in an attempt to evoke questions; at age eleven, he had the courage to declare, "I'm a girl." Milton Beyer stood stone-faced. Selma Beyer threatened to have him institutionalized. It was never mentioned again. "They were scared to death," says Beyer. "It was not an issue of my sexuality. It was more an issue of a psychiatric problem that the neighbors might find out. So they shut it down completely."

But then puberty arrived, sparking a terrifying hormonal conflict. That enlarged utricle started bleeding, which Beyer describes as "menstruating from my residual uterine tissue." Wayne kept it a secret for four months, thinking: Maybe God is finally turning me into a girl. Finally, the pain grew too intense to hide. The Beyers took Wayne to a urologist, whose draconian solution was to inject silver nitrate—a chemical cautery agent to stop blood flow—into the urethra. The burning, says Beyer, was "the most horrendous pain imaginable." The doctor couldn't tell where the bleeding was coming from, but the injections continued. Years later, when Beyer told a therapist what had happened, he was horrified. "My god," he said, "you were raped and tortured for four months."

But then puberty arrived, sparking a terrifying hormonal conflict. That enlarged utricle started bleeding, which Beyer describes as "menstruating from my residual uterine tissue." Wayne kept it a secret for four months, thinking: Maybe God is finally turning me into a girl. Finally, the pain grew too intense to hide. The Beyers took Wayne to a urologist, whose draconian solution was to inject silver nitrate—a chemical cautery agent to stop blood flow—into the urethra. The burning, says Beyer, was "the most horrendous pain imaginable." The doctor couldn't tell where the bleeding was coming from, but the injections continued. Years later, when Beyer told a therapist what had happened, he was horrified. "My god," he said, "you were raped and tortured for four months."

Eventually, the nitrate caused an obstruction that backed up the urine flow into the bladder and then into the kidneys, leading to acute renal failure. During surgery, thirteen-year-old Wayne coded and had to be resuscitated, spending three weeks in the hospital. Doctors never did discover the original problem, although the bleeding did cease.

In the years that followed, Beyer was an academic over-achiever—commuting four hours daily to attend the prestigious Bronx High School of Science, then earning degrees from Cornell and Penn. But there was always emotional distance: Keep friends at arm's length. Don't drink or do drugs, for fear of lowering inhibitions. Live on the periphery. At Cornell, Beyer lived at the Young Israel House for two years and spent a junior year abroad in Israel. Mostly, she recalls her college experience as being dominated by lots of science labs and few intimates. "I don't think anyone would remember that I existed," Beyer says. "I was on this knife's edge, this fear that somehow I would be outed and people would know. I lived with a mask on, feeling I was defrauding my closest friends."

The only exception was a girlfriend, Shula. They had met in high school, and Beyer got close to her just before heading to Cornell. Shula remained a best friend and intimate, eventually becoming Beyer's wife during medical school and bearing the couple's two sons.

Regarding the issue of sexual orientation, Beyer has described herself as bisexual. Despite erotic feelings toward men, Beyer says she never felt like a gay man; how would such a thing be possible if you're really a woman? Nor is she now specifically attracted to one gender or the other. "It's who you are, not who you love," she says. "People ask me what I am now, and I say, 'I don't really care. I'm just looking for love.'"

The burden of not being able to express her true identity led to a peripatetic existence. Beyer worked as a physician and surgeon in northwestern Kenya, completed a residency at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, then traveled to the foothills of the Nepalese Himalayas, serving as an eye surgeon for the World Health Organization's Prevention of Blindness Program. Years earlier, while recovering in the hospital at thirteen, Beyer had announced a desire to become a doctor "so nobody would ever have to suffer like me." Originally, the plan was to focus on pediatrics—but because it was a predominantly female specialty, Beyer was afraid people might start asking questions about gender identity. The decision to turn to ophthalmology was telling, Beyer says. "There's really nothing in any eye disease that's gender specific, other than congenital diseases," she notes. "I've thought about that. Why did I end up in a subspecialty that had nothing to do with who I was?"

Beyer thrived during a seven-year stint as a glaucoma and retina specialist in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, providing care for a large population of underserved (and underinsured) African American and Cajun patients. But by 1990, the weight of living as a man had become almost too much to bear. "I was chronically suicidal," says Beyer, who retired from clinical practice, separated from Shula, and embarked on what was essentially a decade of stops and starts along the road to gender transition.

A big moment occurred in 1992 with a simple act—shaving off a mustache. "That was my camouflage," says Beyer, who had sported one for more than two decades. "I couldn't go out as a woman with a mustache. It was forcing me to live as a man." Slowly, cautiously, Beyer began to transition—taking estrogen and undergoing painful electrolysis, as well as scalp revision surgery to counter the onset of male pattern baldness. But severe depression and a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder—as well as a relationship with the woman, Cathy, who became his second wife in 1997—put the process on hold.

The September 11 terrorist attacks restarted the transition. Beyer attended a good friend's wedding in Manhattan nine days later, and a confluence of events crystallized into an epiphany. Beyer was approaching fifty. The friend had waited until that age to get married, a lesson that it's never too late to find happiness. The smoke rising from Ground Zero was still visible, a reminder that life is short. At the wedding, surrounded by a handful of childhood classmates, Beyer understood that crippling fear had been preventing a full-on transition—fear of the response from his yeshiva friends, from medical colleagues, from parents who had resisted even contemplating their child's gender issues, from a younger brother who is a professor at the U.S. Naval Academy. That day, Beyer says, "I realized I no longer cared what people thought. That was the critical leap."

In January 2003, Beyer traveled to San Francisco for facial feminization surgery—an eleven-hour procedure involving reconstruction of the forehead, nose, jawline, and chin. That July she underwent four hours of genital surgery consisting of a penectomy, vaginoplasty, and labioplasty. A few months later, Beyer underwent breast augmentation. The "M" was changed to "F" on her driver's license, her passport, and even her birth certificate. "It's like I was reborn," she says.

When it came time to choose a new name, her sons got involved. Beyer's younger son, Jonathan, was thirteen at the time of the surgeries and had known about his father's inner turmoil for nearly a decade, once even looking into a store window and saying, "That's a pretty dress. I'm going to buy you that for your birthday." David, then sixteen and away at prep school, didn't have the cushion of experiencing the transition incrementally, as his younger brother did; the first time he saw his father as a woman, in fact, was at his graduation. Although he admits it was difficult for a while, eventually he discovered that the biggest change in his life was simply that his father seemed happier.

But the name—that was important to the boys. Choose a female name that won't embarrass us on our college applications, they told her. Pick a gender-neutral name. So she officially became Dana Beyer, and her sons usually call her by her first name. Now when she hears the name Wayne, Beyer says, "It's not me anymore. There's a bit of a cringe factor. But it always had a cringe factor, even when I was little."

Conventional wisdom in the trans-gender community suggests that half of one's friends and family might be lost in the wake of a transition. But in the end, "I have lost no one, with the exception of my wife as a wife," says Beyer, who remains good friends with Cathy. "I have regained all of these friendships, but in a far deeper sense." But what about her parents, from whom Beyer had been emotionally estranged for half a century? "We had never talked about anything of significance," she says, "because the most significant thing in my life was unspeakable."

Even after the facial surgery, when Beyer had been living as Dana for a couple of months, her mother insisted on calling her by her male name. Her father had been characteristically silent. So Beyer decided to fly down to Delray Beach, Florida, and confront the situation head-on. It began awkwardly—especially with her mother, who had long harbored guilt about her use of DES and how it might have affected her child. But within a few hours, the three of them were leafing through photo albums as her parents tried to decide whether she looked more like Aunt Becky or Aunt Frances. Says Beyer: "I have a relationship with my parents for the first time in my life."

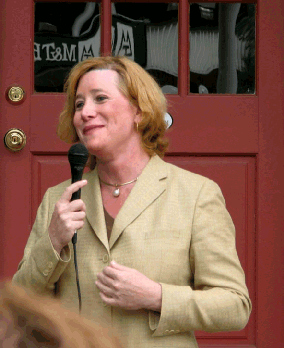

Once introverted, Beyer found new life as a community activist with an unyielding set of opinions, particularly about progressive causes like universal health care. "There aren't enough people who are truly willing to stand up for what they believe, so I'm trying to change that," says Beyer. "Because of my transition, I'm fearless. After what I've gone through, dealing with conservative Democrats or fundamentalist Christians is a piece of cake."

The day after the 2006 election, Montgomery County councilwoman Duchy Trachtenberg offered Beyer a paid position as her senior policy adviser. Beyer worked nearly sixty hours per week— her responsibilities included health and human services, education, civil rights, and intergovernmental relations—until taking unpaid leave to return to the campaign trail. Beyer also serves as vice president of Equality Maryland, sits on the board of directors of the National Center for Transgender Equality, and is a founding director of Teach the Facts, a group that has waged a legal battle with conservatives over curriculum changes that included discussion of transgender issues. Her increased public profile has turned her into a bit of a lightning rod in the county. "Some of my political adversaries here are going around saying, 'She thinks she's the tenth councilmember. She's not acting like a staff member,'" she says. "Well, this is who I am. I'm making a difference."

Some of her opponents, however, have done more than grumble. Beyer has received hate mail and the occasional death threat. Her son David has even tried to convince her to wear a bulletproof vest. "He's afraid I'm going to end up like Harvey Milk," says Beyer, who dismisses the notion with a shrug. "My whole goal is to normalize my community and myself."

Beyer has occasionally found herself embroiled in ugly confrontations, one of which resulted in her suing the county under a 2007 law—prohibiting discrimination based on "gender identity and expression"—that she and Trachtenberg helped craft. After Beyer was accused of intimidating petition gatherers representing a group formed to oppose the law, the county ethics commission launched an investigation. When Beyer learned that the investigation had included having a technician secretly scour her office computer, she filed a complaint with the county human rights commission. Then, contending her complaint was ignored, she sued Montgomery County for $5 million; the case is pending. "If you sue for an apology," she explains, "nobody pays much attention to you."

Meanwhile, Beyer continues to aim for a seat as a state delegate, so she has worked to enhance her credentials. In July 2008, she completed a three-week program for senior executives in state and local government at Harvard's Kennedy School. During the 2008 presidential race, she attended the Democratic National Convention and served on the Obama campaign's LGBT steering committee. Last June, she found herself in the East Room of the White House as part of a group observing the fortieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, the Greenwich Village confrontation considered the modern genesis of the gay rights movement. After Obama spoke he worked the room, finally arriving at Beyer.

"Mr. President, I'm Dana Beyer. I'm a retired eye surgeon," she told him. "And when I'm elected next year, I'm going to be the first transgender state legislator in American history."

"That's great," the President said with a wide smile. "Go for it."

Brad Herzog '90 is a CAM contributing editor and author of the new travel memoir Turn Left at the Trojan Horse.