Cornell in the Cold War (Part I)

This is the first of two articles derived from ongoing study of Cornell history from 1945 to the present by Glenn Altschuler and Isaac Kramnick. Altschuler, PhD ’76, is the Litwin Professor of American Studies, dean of the School of Continuing Education and Summer Sessions, and vice president for university relations. Kramnick is the Schwartz Professor of Government. They are the co-authors, along with Laurence Moore, the Newman Professor of American Studies and History, of The 100 Most Notable Cornellians. In their research, Altschuler and Kramnick have had access to many presidential papers in the Cornell archives, some of which had never before been open to scholars.

This is the first of two articles derived from ongoing study of Cornell history from 1945 to the present by Glenn Altschuler and Isaac Kramnick. Altschuler, PhD ’76, is the Litwin Professor of American Studies, dean of the School of Continuing Education and Summer Sessions, and vice president for university relations. Kramnick is the Schwartz Professor of Government. They are the co-authors, along with Laurence Moore, the Newman Professor of American Studies and History, of The 100 Most Notable Cornellians. In their research, Altschuler and Kramnick have had access to many presidential papers in the Cornell archives, some of which had never before been open to scholars.

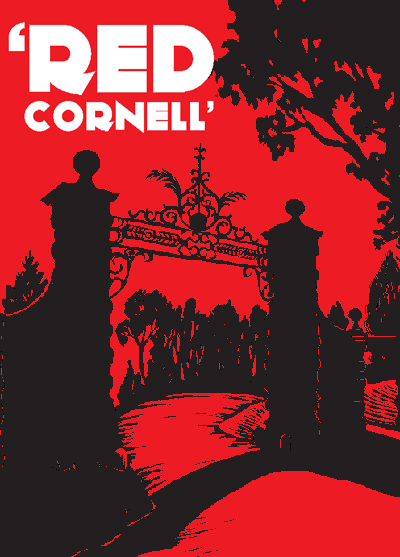

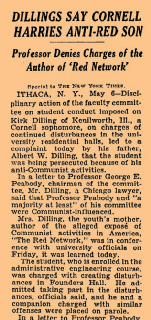

Cornell Goes Bolshevist” proclaimed the New York World-Telegram on October 19, 1943.

The University’s Russian courses, the paper announced, were being taught by communists, making Cornell a breeding ground for “Muscovites.” For the next several days, the paper repeated its accusation in articles and editorials carried in other Scripps Howard and Hearst papers across the country.

The attack was focused on two Russian émigrés, Joshua Kunitz and Vladimir Kazakevich, who had been hired to teach in the Intensive Russian Language and Culture Program, which the University agreed to design for the United States Army in the summers of 1943 and 1944. The Army had chosen Cornell because since 1939 it had offered an innovative Slavic language and studies program funded by the Rockefeller Foundation. For twelve weeks, hundreds of trainees in what was called the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) were brought to Ithaca and immersed in conversational Russian language. The students also took courses in Cornell’s Institute of Contemporary Russian Civilization.

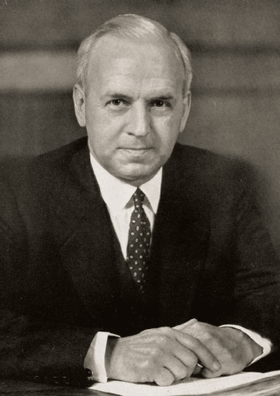

Cornell’s president, Edmund Ezra Day, had been delighted that the Army asked his university to play an important role in the war effort. “Because of Cornell’s well-known reputation as a pioneering institution,” he wrote after the Soviet Union had become an ally of the United States, “strong representations were made that it take a lead in the development of modern Russian studies.” Answering this call was what Day had in mind when he insisted in his 1937 presidential inaugural address that universities had a “social obligation” to “add to the common weal.” Not that the Dartmouth- and Harvard-educated former economics professor—who before coming to Cornell had taught at Harvard and Michigan and been director for the social sciences with the Rockefeller Foundation—didn’t see problems in such activities. “We knew,” he later noted, “that we were taking a calculated risk in agreeing to run the Army program,” given the lack of “authentic and validated information” about Soviet Russia and “an even worse lack of critically trained teachers.” And, of course, given the potentially controversial nature of the instruction.

Several weeks before the first World-Telegram attack appeared, Day asked Cornelius deKiewiet—a professor of history and director of the Army program that sponsored language and culture courses in German, Italian, Czech, and Chinese, as well as Russian—to inform the Cornell faculty about the initiative. Controversial material would be taught in these courses, he conceded, but this was the intention of the Army authorities responsible for the program. If instructors had “burning convictions” about their subjects, they should lay out their views and “provide the opportunity for free discussion.” DeKiewiet was as concerned with courses about our enemies, Germany and Italy, as he was about Russia, a “friendly and associated power.” In a surprisingly capacious vision of academic free inquiry, he wrote:

There is no objection whatever to handling controversial material if the purpose is to improve the understanding or promote the efficiency of Army trainees. Marxism and communism, the genuine achievements of Hitler or Mussolini, attractive characteristics of enemy peoples—these can and should be freely handled. The ASTP wishes its trainees to have a mature and sympathetic comprehension of other areas and peoples.

President Day responded to the World-Telegram‘s charge that students were being indoctrinated by “communist” faculty in a January 7, 1944, letter to Cornell’s Board of Trustees:

For reasons which are relatively easy to understand, the only available instructors who have an intrinsic knowledge of contemporary Russian conditions are individuals who had been repeatedly in Russia during the period since the revolution. Perforce, most, if not all of those individuals have exhibited “Russian sympathies”; otherwise they would not have had opportunities for close observation of developments under the present Soviet regime.

Day then reviewed the careers of Kunitz and Kazakevich, their study in America, and their travels in and writings about Soviet Russia. “As far as we can see,” he concluded, “there is nothing in [the] entire record that suggests ‘un-American activities.’ ” Having talked with the Russians, Day was prepared to vouch for their loyalty and their “thorough” commitment “to the American way of life.”

Having reassured the trustees, Day turned next to calming any fears in the general public about “Red Cornell.” In March 1944 he stated the University’s position in the prestigious Saturday Review. Written in an age before professional speech writers, “So Cornell’s Going Bolshevist! The Strange Case of the Russian Courses,” is a beautifully crafted, at times deeply moving, essay, interwoven with a history of Cornell and an almost lyrical paean to freedom of inquiry.

It was an “unpleasant experience,” he began, with wry understatement and a touch of intellectual disdain, to find the “good name” of his institution “aspersed in the columns of a metropolitan daily.” Day felt particularly sad for anxious alumni, fearing that their alma mater “is pulled down from the serene heights on which their adolescent imaginations had placed her.” He then addressed head-on what he referred to, in terms not yet part of common American political parlance, as the World-Telegram‘s “witch-hunting.” It wasn’t the first time his institution had been so publicly attacked, he pointed out, recalling the accusation in the nineteenth century of “Godless Cornell.” Having its “faith tested” could be salutary, he proclaimed, if it forced Cornellians to realize that “a principal obligation of any university is a certain fearlessness about the knowledge which it professes and the end which it pursues.”

Little could President Day know in 1944 that Cornell’s encounter with a metropolitan daily was a mere minor prelude to the full-blown drama of postwar anti-communist hysteria— the phenomenon we now know as McCarthyism—that would engulf the University for the next twenty years, requiring Day and his successor, Deane Waldo Malott, to walk a fine line, balancing their commitments to academic values with demands of loyalty and Americanism. In meeting these challenges, Cornell’s presidents, administrators, and faculty would sometimes falter and stumble as the weight of the political world outside East Hill fell upon their shoulders. For the most part, however, in the face of pressure from trustees, politicians, and the popular press, they bent but did not break.

Robert Fogel ’48, who would win the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1993, was Cornell’s leading student radical in the late Forties, when Soviet-American friendship was replaced by the bitter suspicions of the Cold War. The son of Russian immigrants, he concentrated on physics and chemistry at New York City’s prestigious Stuyvesant High School. At Cornell, Fogel switched to economics and history—as well as political agitation. He became head of the Marxist Discussion Group and the campus chapter of American Youth for Democracy (AYD), the successor to the Young Communist League and an organization that Attorney General Tom Clark placed on his 1947 subversive list. The Alumni News estimated that in Fogel’s last years on campus the AYD had about a dozen members, with most radical students preferring either the Henry Wallace politics of the Progressive Citizens of America or the Students for Democratic Action, which was linked to its anti-Stalinist parent organization, Americans for Democratic Action, founded by Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Reinhold Niebuhr.

Robert Fogel ’48, who would win the Nobel Prize for Economics in 1993, was Cornell’s leading student radical in the late Forties, when Soviet-American friendship was replaced by the bitter suspicions of the Cold War. The son of Russian immigrants, he concentrated on physics and chemistry at New York City’s prestigious Stuyvesant High School. At Cornell, Fogel switched to economics and history—as well as political agitation. He became head of the Marxist Discussion Group and the campus chapter of American Youth for Democracy (AYD), the successor to the Young Communist League and an organization that Attorney General Tom Clark placed on his 1947 subversive list. The Alumni News estimated that in Fogel’s last years on campus the AYD had about a dozen members, with most radical students preferring either the Henry Wallace politics of the Progressive Citizens of America or the Students for Democratic Action, which was linked to its anti-Stalinist parent organization, Americans for Democratic Action, founded by Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and Reinhold Niebuhr.

Although his followers were few, Fogel put Marxism on the postwar campus map. In speeches, public debates, and letters to the Daily Sun, he proclaimed that communists “fight for anything that will help the majority of the people.” Fogel’s views would infuriate some trustees, but they seldom shocked the student body, a majority of whom were World War II veterans. A 1948 Daily Sun poll of 500 students indicated that 70 percent of the respondents believed that “we should continue to try to cooperate with Russia.” While 27 percent felt the work of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was “valuable,” 35 percent thought it “actually does harm”; the rest had no opinion.

Unlike most Cornell students, the mayor of Ithaca was shocked by Fogel’s Marxism. In May 1946, citing an ordinance prohibiting littering, he banned AYD leafleting downtown. More important, some Cornell trustees—including Nicholas Noyes 1906 of Eli Lilly and Co., Franklin Olin of Illinois’s First National Bank, John Collyer 1929 of B. F. Goodrich, and Horace Flanigan 1912 of New York’s Manufacturer’s Trust—were convinced that, as Olin put it, Cornell was “riddled with communism.” Day reassured angry alums and trustees that Fogel’s AYD was “a small, highly vocal, and virtually impotent” organization. As if to minimize any need for concern, Cornell’s dean of students noted that, like Fogel, “most of its members are Jewish” and that they are “attracting almost entirely their own type.”

The trustees had more than Fogel to fret about. The film star Adolphe Menjou 1912, who had attended Cornell without completing a degree, told HUAC that there was “a group of communists functioning in Ithaca.” Collier’s Magazine photographed a Willard Straight Hall meeting of the Marxist Discussion Group for an article it was preparing on campus reds, and in 1947 Eugene Lyons, author of The Red Decade, singled out Cornell in a pamphlet, “The Enemy in Our Schools,” published by the Catholic Information Society. Other colleges may have been as “deeply infiltrated” by communists, but few others, he claimed, “have been as frivolous in defending the infiltration or as stubborn in persisting in the error after it has been exposed.” Lyons recycled the charges against the wartime Russian program, “honeycombed with notorious pro-Soviet propagandists,” and accused the University of using the same faculty, “seasoned mouthpieces of Red propaganda,” when it revived the program in 1946.

In a series of long letters in 1949, trustee Nicholas Noyes complained that Cornell was ‘unwittingly providing a sounding-board for a lot of reds, pinks, and crackpots.’ Several trustees were suspicious, as well, that in collaborating with the State of New York to create a School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell was opening the door to subversives. No matter that Governor Thomas Dewey, in his address at the ILR opening in November 1945, described it as “a school which denies the alien theory that there are classes in our society and that they must wage war against each other.” President Day agreed that ILR could well help the nation turn “from continuing warfare between the contending parties in modern industrial enterprise, and toward increasing cooperation.” Nonetheless, by 1947, trustee Frank Gannett 1898 cautioned Day that the ILR faculty “can be in sympathy with the working class but that does not mean that they should directly or indirectly promote collective bargaining or unionization.” A year later, Day was informed that “some trustees . . . still regard [ILR] with horror as an incubator of radicalism.”

Several trustees were suspicious, as well, that in collaborating with the State of New York to create a School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Cornell was opening the door to subversives. No matter that Governor Thomas Dewey, in his address at the ILR opening in November 1945, described it as “a school which denies the alien theory that there are classes in our society and that they must wage war against each other.” President Day agreed that ILR could well help the nation turn “from continuing warfare between the contending parties in modern industrial enterprise, and toward increasing cooperation.” Nonetheless, by 1947, trustee Frank Gannett 1898 cautioned Day that the ILR faculty “can be in sympathy with the working class but that does not mean that they should directly or indirectly promote collective bargaining or unionization.” A year later, Day was informed that “some trustees . . . still regard [ILR] with horror as an incubator of radicalism.”

In the immediate postwar years, trustees worried a lot about what happened on campus. In a 1947 speech at Barnes Hall, NAACP leader Roy Wilkins described the campaign against communism as “stupid, foolish, and at times hysterical . . . [and] anyone who challenges the status quo seems to be branded as communistic.” Along with the Ithaca Chapter of the American Veterans Committee and the Daily Sun, Fogel urged that ROTC training, a requirement for all male students in Cornell’s contract colleges, be made voluntary. After voting twice to retain compulsory ROTC, the Student Council endorsed the reform in December 1947; the faculty and administration, however, would not be moved.

In the immediate postwar years, trustees worried a lot about what happened on campus. In a 1947 speech at Barnes Hall, NAACP leader Roy Wilkins described the campaign against communism as “stupid, foolish, and at times hysterical . . . [and] anyone who challenges the status quo seems to be branded as communistic.” Along with the Ithaca Chapter of the American Veterans Committee and the Daily Sun, Fogel urged that ROTC training, a requirement for all male students in Cornell’s contract colleges, be made voluntary. After voting twice to retain compulsory ROTC, the Student Council endorsed the reform in December 1947; the faculty and administration, however, would not be moved.

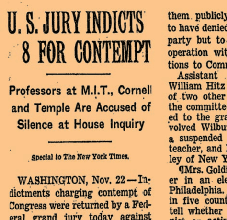

To the trustees, moreover, too many professors seemed to be radicals or fellow travelers. They noted that history professors Paul Gates and Curtis Nettles opposed President Truman’s 1947 proposal for aid to Greece and Turkey in their battle against communism, and that some Cornell scientists refused to work on government grants if the research was “classified” and therefore secret. They were further alarmed when—concerned about the arbitrary dismissal of faculty from American universities—Robert Wilson, director of the Laboratory of Nuclear Studies, Nobel laureates Hans Bethe and Peter Debye, chemist Simon Bauer, and physicist Philip Morrison formed a committee, affiliated with the Federation of American Scientists, “to investigate the spy investigators.”

The trustees took note, as well, of the position of the faculty on the sensitive issue of student organization membership lists. For years, concerned that students on academic probation might participate in student organizations, the faculty, with the support of the Student Council and the Daily Sun, had required that all registered groups submit membership lists to the administration. In January 1948, Fogel’s Marxist Discussion Group and the Cornell chapter of the Young Progressive Citizens of America refused to comply, fearing that the students named would then be under suspicion of disloyalty. Setting what the Sun described as “an all-time attendance record,” the University faculty met in February and, by a vote of 155 to 149, repealed the policy. With considerable justification, President Day feared that the trustees would read this vote “as a victory of the campus reds” and for Fogel. Three months later, his assistant, Whitman Daniels, wrote to Day that “these queries in regards to communism and kindred activities at Cornell seem to be coming in with such frequency that I am almost inclined to believe that we should adopt a form letter by way of reply.”

The trustees took note, as well, of the position of the faculty on the sensitive issue of student organization membership lists. For years, concerned that students on academic probation might participate in student organizations, the faculty, with the support of the Student Council and the Daily Sun, had required that all registered groups submit membership lists to the administration. In January 1948, Fogel’s Marxist Discussion Group and the Cornell chapter of the Young Progressive Citizens of America refused to comply, fearing that the students named would then be under suspicion of disloyalty. Setting what the Sun described as “an all-time attendance record,” the University faculty met in February and, by a vote of 155 to 149, repealed the policy. With considerable justification, President Day feared that the trustees would read this vote “as a victory of the campus reds” and for Fogel. Three months later, his assistant, Whitman Daniels, wrote to Day that “these queries in regards to communism and kindred activities at Cornell seem to be coming in with such frequency that I am almost inclined to believe that we should adopt a form letter by way of reply.”

Fogel didn’t always win. In early 1949, a year after his graduation, Fogel was still on campus. On behalf of his Marxist Discussion Group, he invited Eugene Dennis, secretary of the American Communist Party—then under indictment in federal district court for advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government—to speak at Cornell. The Faculty Committee on the Scheduling of Public Events, however, unanimously turned thumbs down, declaring: “No person under indictment should be permitted to substitute the campus of Cornell University for the legally constituted courtroom as a forum to plead his case.” At a rally that April, Fogel charged that the faculty caved in because it was “unrepresentative, lacking professors who believed in Marxist doctrine.”

The trustees saw a different faculty. In a series of long letters in 1949, Nicholas Noyes complained that Cornell was “unwittingly providing a sounding-board for a lot of reds, pinks, and crackpots.” Noyes endorsed Day’s commitment to fire self-professed communist professors, but he also wanted to regulate “borderline teaching,” which “stops just short of communism.” Trustees also complained about “pinko” textbooks. When Frank Gannett, J. Howard Pew, John Collyer, and W. C. Teagle objected to classroom use of L. Tarshis’s “subversive, wicked, and vicious” Elements of Economics, Day and Provost Arthur Adams felt the heat—and asked C. C. Murdock, PhD 1919, dean of the faculty, to investigate. Elements of Economics, Murdock reported, “adopts the approach of Keynes. . . . It is admittedly modern and somewhat to the left.”

Deciding to take no action, Adams sought to placate the trustees, assuring them, a bit disingenuously, that “no member of the economics department shares Tarshis’s viewpoint,” but allowing himself to add that “the young men and women who are now studying economics will some day be confronted with versions of this doctrine [Keynesianism]. . . . It would be doing them a disservice to withhold ideas which are a part of current economic thought and to fail to train them in the ability to form and defend their own judgments.”

The trustees tried a different tack as well. Endorsing John Collyer’s proposal for a required course on “the American way of life,” Frank Gannett claimed it “would impress on our students the great benefits that we have derived from our system of government and the opportunities it has made possible.” President Day agreed, writing to Devereux Josephs, president of the Carnegie Foundation, “That we need such a program of indoctrination seems to me incontrovertible. . . . We are faced with an enemy who is engaged in an all-out mass indoctrination by authoritarian means . . . [and] I doubt very much whether we can relax and assume that in a free society no counter propaganda need be undertaken.”

Day also sent the proposal to Dean Murdock, who appointed a faculty committee; they did not like the idea of “a program of indoctrination”—and refused to make the course an undergraduate requirement. Scrambling, perhaps to save face, the University sponsored a series of lectures and conferences entitled, suitably enough, “America’s Freedom and Responsibility in the Contemporary Crisis,” funded with a $10,000 Carnegie grant for speakers.

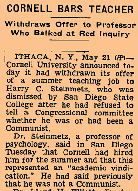

Clearly, President Day worked hard—and repeatedly—to respond to the trustees without compromising academic freedom. An especially thorny challenge came when Nicholas Noyes informed him that Marshall Stearns, who had just been hired by Cornell’s English department, had been engaged in “subversive activities” at his former institution, Indiana University. After checking with Indiana’s president, Herman Wells, who verified that the allegations were true, Day (for the first and only time, as far as we know) applied a political test for the retention of a faculty member. “Fortunately he is on a limited-term appointment for three years,” Day wrote to Noyes. “He was already hooked up with us before I had my first report from you . . . and I do not see that anything more can be done at the present time.” But he wanted Noyes to know that, as president, he had “put the dean of the college and the chairman of the department on notice with respect to the record the man made at Indiana . . . if and when the question of Dr. Stearns’s retention or possible promotion comes up for forward action.” Stearns soon left Cornell for what became a distinguished career as an expert on American jazz.

As the Cold War shattered Day’s hopes for Soviet-American cooperation and intensified attacks on academic freedom, he told the Board of Trustees that “a member of the Communist Party cannot be free or honest, and therefore has no place on the university faculty.” He believed, however, that students should see all points of view, so communists would be allowed to speak on campus—but only if questions were allowed. After the Marxist Discussion Group brought a speaker who explained the latest trends in Soviet genetics, he pointed out proudly, “A competent group of animal and plant majors matched minds with him after his lecture and were able to win out very substantially.”

Day went along with a federal mandate that applicants for Atomic Energy Commission fellowships sign a loyalty affidavit, but he opposed congressional investigations of the curriculum. When Congressman John S. Wood of HUAC asked for a list of all texts used in the social sciences, Day responded that compliance would be difficult and expensive. “More important, what does the committee intend to infer from such a list? Suppose in some courses Karl Marx’s Das Kapital is on the list of reading, or sections of the Communist Manifesto. . . . These young people ought to have some acquaintance with these documents. It does not follow because they are cited or used that communism is being taught.”

Day knew that Cornell’s Board of Trustees was not immune to the anti-communist hysteria sweeping the country. But he told Frank Gannett that when Franklin Olin argued that “our college campuses were riddled with communism,” or “calls a New Dealer a communist,” or “looked for a red under every bed, even at Cornell,” he “just does not know what he is talking about.” Nonetheless, “in view of Mr. Olin’s great wealth” and the prospect that “he might reasonably give us money,” Day held his tongue to Olin himself.

In contrast, Day tried to persuade Nicholas Noyes about the values of academic freedom. After reassuring Noyes that he, too, abhorred communism and thought communist faculty should be fired, Day illustrated the central role of free discussion in “our American way of life” with the story of a student who had recently “confounded a radical speaker and brought an end to a meeting with a simple question to which he wanted a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer. If there were a communist government in the United States, would that government permit a meeting such as this?”

In 1949, two months before his deteriorating heart condition forced him to resign his presidency, Day was interviewed by Mutual Radio News. He defended ejecting communists from teaching positions, “where their fettered minds have no legitimate place.” But, he warned, this must not “give rise to a sort of hysteria, in which independent and essentially forward-looking thinkers are scrapped along with real members of the fifth column.” Day concluded with a plea that Americans develop an explicit definition of “the essential ingredients of the American way of life.” Echoing the Cornell historian Carl Becker, Day challenged his radio audience to do what their “founding fathers did not do . . . to spell out the responsibilities, individual and collective, which go along with the rights they established . . . responsibilities without which our rights today cannot be permanently retained.”

Part II continues in our September/October feature, “The Morrison Case.”