At the Eighty-Third Academy Awards in February, Javier Bardem and Josh Brolin—a dashing pair of chisel-jawed, dark-haired actors clad in matching white dinner jackets—presented the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay. In his suave Spanish accent, Bardem listed the nominees: Another Year, The Fighter, Inception, The Kids Are All Right, The King’s Speech. Brolin then opened the golden envelope and announced the winner: David Seidler ’59 for The King’s Speech, a historical drama about George VI’s struggles to overcome his stutter with the help of an unconventional speech therapist.

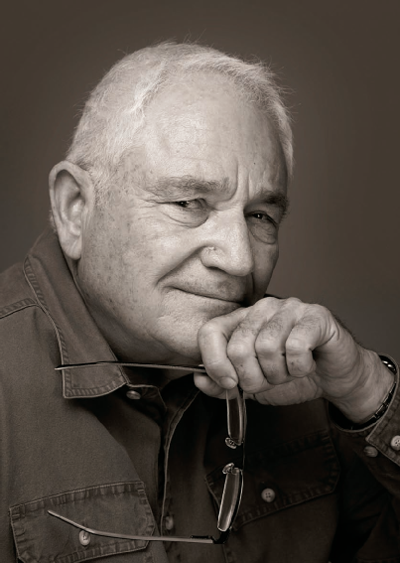

Seidler took the stage, looking a bit lost; he needed help finding the microphone, which was so slender as to be almost invisible. But once he located it, he brought the house down. “My father always said to me,” the courtly, white-haired Seidler told the elegantly clad audience, “I would be a late bloomer.”

At seventy-three, Seidler became the oldest person to win an original screenplay Oscar—the pinnacle of a career that began in the mid-Sixties with six episodes of the long-forgotten TV series “Adventures of the Seaspray.” Until The King’s Speech, Seidler’s best-known film was the 1988 Francis Ford Coppola picture Tucker: The Man and His Dream, starring Jeff Bridges as an ill-fated automotive entrepreneur. Much of his work had been in television biopics, including Malice in Wonderland (about gossip mavens Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons), Onassis: The Richest Man in the World, and Come On, Get Happy: The Partridge Family Story.

For Seidler, The King’s Speech was a labor of love. Not only did it resonate personally—a childhood stutterer himself, he’d been inspired by the king’s strides in overcoming his speech impediment—but the film was decades in the making. In the early Eighties, he’d asked the king’s elderly widow (Elizabeth, the Queen Mother) for permission to write about her husband’s speech problems, but she’d told him the subject was still too painful and requested that he wait until her death. He agreed—never imagining that she’d live another two decades, passing away in 2002 at the age of 101.

Born in London, Seidler came to the U.S. with his parents as a toddler to escape World War II; he claims that his stammer began on the transatlantic crossing. He grew up on Long Island and majored in English on the Hill—where he first put his mind to the idea of writing about George VI. “That organ, however, was easily distracted by girls,” Seidler recalled in an essay published in the Daily Mail last December, “so nothing much came of the effort.”

When he finally tackled the subject in late 2005, he wrote it as a stage play; once the movie rights were optioned he swiftly adapted it to the screen. Directed by Tom Hooper (who helmed the TV miniseries John Adams), The King’s Speech stars Colin Firth as Bertie, the future King George VI; Helena Bonham Carter as his wife; and Geoffrey Rush as speech therapist Lionel Logue. It was nominated for twelve Oscars and won four, including Best Picture; in addition to his Academy Award, the film earned Seidler a BAFTA (the British Oscar), a Critics Choice Award, and a Golden Globe nomination, among other honors.

In mid-April, Seidler returned to Ithaca to introduce the film at Cornell Cinema and answer questions from the audience. It was just the second time he’d been back to campus since his graduation; his previous visit was in 1979. Before the screening, Seidler spoke with CAM over drinks at the Statler Hotel.

Cornell Alumni Magazine: What’s it like to win an Oscar?

David Seidler: It’s most peculiar. It’s really very strange. No pre-imagining quite prepares one. One does fantasize. What if I win? How will I feel? And then it happens and it’s somewhat otherworldly, like being abducted by aliens.

CAM: Do you remember walking from your seat to the stage?

DS: I was very conscious of “Don’t trip, don’t fall on your face, it’s going to look bad.” When I got up there Javier Bardem and Josh Brolin turned it over to me—but nobody had warned me that the microphone is very thin and black, and of course everyone is wearing tuxedos. I had trouble finding the mike, which was a little embarrassing.

CAM: Had you prepared a speech—and if so did you stick to it?

DS: I had loosely prepared some remarks. I couldn’t stick to them very well because my first line got too long a laugh, and they count that in your forty-five seconds. I had only given my first sentence when this damn prompter was saying, “Wind it up, wind it up.” I had to leave out all my thank yous.

CAM: Was there actually someone giving you the wind-up sign?

DS: It’s a digital prompter that says WIND IT UP in big red letters.

CAM: At one of the most important moments of your life? That had to be distracting.

DS: Yeah, a little bit. But nobody wants to listen to the writer.

CAM: As you noted in your speech, you’re the oldest person ever to win for Best Original Screenplay. In our youth-obsessed culture, was that particularly sweet?

DS: It’s a nice victory lap. It has added a zero to my price, which is really good. I’ve got a lot of work. Everybody takes me terribly seriously. It’s a wonderful thing. But I’m glad it has happened to me now, and not when I was younger.

CAM: Why?

DS: I can see how it can mess up your head. It’s so divorced from reality. It’s so bizarre that I think a younger person could get really off track, because you can start taking yourself too seriously.

CAM: Why did you want to write about King George VI’s speech problems?

DS: I was a profound stutterer, and a childhood of stuttering is no fun. But during the war my parents encouraged me to listen to the king’s speeches and they would say things like, “David, he was a far worse stutterer than you, but listen to him now.” He was never perfect, but he was able to give stirring wartime speeches that rallied the troops, the commonwealth, the free world.

CAM: So at the time, the average Brit knew he had a stutter? It wasn’t concealed, like FDR’s paralysis from polio?

DS: It was hard to hide. FDR’s legs you could put a blanket over; you could avoid showing him standing up. But if the king has to speak and he can’t, you can’t hide that. So everybody knew it but nobody said anything. It was swept under the carpet. That’s why very little was written about it, or about Lionel Logue, because the royal stutter was a source of embarrassment. In those days, it was called a speech defect—and if you had one you were a defective person. You couldn’t have the King of England called a defective person. So it was known throughout England but never talked about.

CAM: How did you feel about the film getting an R rating, solely for the scene in which the “f-word” is used as a means of speech therapy?

DS: To rate The King’s Speech the same as, say, Saw 3-D makes you wonder, what are they smoking and where can I get some? On television and radio, you can advertise a film called Little Fockers. Who are we kidding? There’s a great deal of hypocrisy. Those words are in that scene for a specific purpose. It is not puerile, there’s no sexual innuendo, no insult, no threat. It’s purely for therapeutic reasons.

CAM: Why was that scene so important to include?

DS: It’s one of the very few scenes that I could not prove actually happened—but I know it must have, or something very similar to it, because it’s a cathartic moment that every stutterer goes through. In my case I was sixteen. I knew that if I didn’t get a good handle on my stutter by late adolescence, my chances went down precipitously, because the older you get, the harder it is to deal with. I was sixteen, hormones were raging, I couldn’t ask girls out on a date—and even if I could and they said yes, what was the point? I couldn’t talk to them.

CAM: So how did you cope with it?

DS: I got very discouraged and depressed at first, but I’m not a depressive personality. I don’t stay down long. I get angry. I get defiant. So I started verbalizing in my bedroom, jumping up and down on my bed, basically the f-word. And my thoughts went something like this: “This is f-wording unfair. Why have the gods visited this affliction upon me? I haven’t done anything terribly wrong; I didn’t sleep with my mother or kill my father. And if I’m stuck with this affliction the rest of my life, f-word you all. You’re stuck with listening to me, because I am not going to remain silent. I have a right to be heard.” And that psychological turn was the beginning. Within two weeks my stutter had, to a large extent, melted away.

CAM: Why did you agree to the Queen Mother’s request that you wait until after her death to write about her late husband’s speech problems?

DS: That’s when my American friends realized I really am still a Brit, because Americans don’t understand it. I am still a Brit, even though I am also an American citizen; I carry both passports. And when the Queen Mother says to an Englishman, “Please wait,” you wait.

CAM: Did you understand why she wanted you to hold off?

DS: I did. It had been such a profoundly painful experience for her, and she was still so embittered that David [King Edward VIII] had abdicated, had not done his job, had forced her husband to become king when he didn’t expect to be king, hadn’t been trained to be king. He wasn’t even qualified to be king with his speech impediment and his fragile health. And she felt, with a fair degree of justification, that this had killed him, that he had died prematurely. She didn’t want to be reminded of it, and I could get that. And I didn’t think I was going to have to wait that long.

CAM: What was it like to see it finally brought to the screen?

‘I am still a Brit, even though I am also an American citizen. And when the Queen Mother says to an Englishman, “Please wait,” you wait. ‘ DS: It was a huge relief. This movie almost didn’t get made so many times. The financing was so tricky. After a few days of rehearsal and seeing Colin nail it, I thought, My goodness, it’s not only getting made, it’s getting made well.

CAM: Can you describe a scene that you find particularly affecting?

DS: There’s a scene after Bertie has had a very bad time with his father, who has bullied him about giving a speech on the radio—”Spit it out, boy!” He’s lying in his study with a wet towel over his eyes, and he gets up angrily to put on the phonograph record that Logue has given him, expecting to hear himself stutter. And of course we hear him speaking Hamlet’s soliloquy brilliantly, and Tom [Hooper] did something really wonderful. You see something come into lower frame; it’s Elizabeth in her dressing gown. And you pan up and see her face, and for the first time she’s hearing her husband speak beautifully. I was terribly moved by that scene.

CAM: What’s next for you?

DS: I have three movies signed up. I’m doing a script called The Lady Who Went Too Far, about Lady Hester Stanhope, who went to the Middle East during the Napoleonic Wars and became a female Lawrence of Arabia. I’m doing a rewrite of a script called Judge for Robert Downey Jr. And I sold to the producing team of the Bourne and Indiana Jones movies a script called The Games of 1940, based on a true story about the Olympic games, which officially never took place. They were scheduled to be in Tokyo, but they didn’t happen. In Stalag 13A near Longwasser, Nuremberg, 150,000 Allied prisoners of war were being kept in appalling circumstances to crush their spirit. They decided that, to retain their humanity, they would hold an international prisoner of war Olympic games in 1940, and they did it without the Germans knowing.

CAM: Does having won an Oscar affect your creative process? When—like every writer—you sit down alone to work, does something feel different?

DS: I don’t know. I haven’t worked for seven months. It’s very disconcerting. It began with the Telluride Film Festival and it’s been nonstop. After the Oscars I went to New Zealand for a month to chill out. Now I’m back and I’ve got to get to work.

CAM: Last question: Where do you keep your Oscar?

DS: I was going to use it as a doorstop. But currently it’s on a cabinet shelf in my dining room, flanked by my two BAFTAs.