They’re the two strong-willed women at the heart of the nation’s debate on school reform. Michelle Rhee ’92 is the former chancellor of the D.C. school system, whose embattled term was marked by bitter controversy over firings and a brusque management style. Randi Weingarten ’80, head of the American Federation of Teachers, is known as a fierce advocate for her union—some say to a fault, with substandard educators kept in the classroom to the detriment of students. The two sat down with CAM to talk about the education debate. Separately.

They’re the two strong-willed women at the heart of the nation’s debate on school reform. Michelle Rhee ’92 is the former chancellor of the D.C. school system, whose embattled term was marked by bitter controversy over firings and a brusque management style. Randi Weingarten ’80, head of the American Federation of Teachers, is known as a fierce advocate for her union—some say to a fault, with substandard educators kept in the classroom to the detriment of students. The two sat down with CAM to talk about the education debate. Separately.

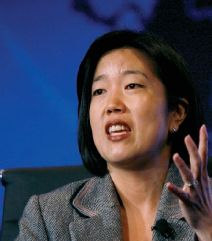

Two Cornellians on opposite sides of the education debate—controversial former D.C. schools chancellor Michelle Rhee '92 and teachers' union leader Randi Weingarten '80—sat down with CAM to talk about school reform. (But not together.)

By Bill Sternberg

They are the two strong-willed women at the heart of the nation's debate on school reform. Both were featured in last year's education documentary Waiting for Superman—one as a hero, the other as a heavy. They have offices seven blocks from each other in Washington, D.C., but are miles apart philosophically. And, yes, reform advocate Michelle Rhee '92 and union leader Randi Weingarten '80 are both Cornellians, a connection they've never discussed.

Rhee, forty-one, catapulted to national prominence—including appearances on Oprah and the covers of Time and Newsweek—as a result of her tumultuous three years as schools chancellor in the District of Columbia. Appointed in 2007 by Mayor Adrian Fenty to overhaul the troubled D.C. system, she fired hundreds of teachers and principals, closed schools, and reorganized the bureaucracy. Test scores rose and enrollment stabilized, but her steamroller style made enemies, not the least of them the Weingarten-led American Federation of Teachers. AFT poured money into the mayoral campaign of Vincent Gray, who defeated Fenty in last September's Democratic primary. Rhee, calling the outcome "devastating," resigned soon after. She has since started a new organization, Students First, to promote school reform. A native of Toledo and the divorced mother of two daughters, Rhee is engaged to former NBA star Kevin Johnson, the mayor of Sacramento.

Rhee, forty-one, catapulted to national prominence—including appearances on Oprah and the covers of Time and Newsweek—as a result of her tumultuous three years as schools chancellor in the District of Columbia. Appointed in 2007 by Mayor Adrian Fenty to overhaul the troubled D.C. system, she fired hundreds of teachers and principals, closed schools, and reorganized the bureaucracy. Test scores rose and enrollment stabilized, but her steamroller style made enemies, not the least of them the Weingarten-led American Federation of Teachers. AFT poured money into the mayoral campaign of Vincent Gray, who defeated Fenty in last September's Democratic primary. Rhee, calling the outcome "devastating," resigned soon after. She has since started a new organization, Students First, to promote school reform. A native of Toledo and the divorced mother of two daughters, Rhee is engaged to former NBA star Kevin Johnson, the mayor of Sacramento.

Weingarten, fifty-three, is the nation's most powerful and highest-profile leader of unionized teachers. She was elected president of the 1.5-million member AFT after serving twelve years as leader of the New York City local, where she was known as a tenacious and combative negotiator. Since becoming AFT president in 2008, she has fought back against efforts to scapegoat teachers, but has embraced changes in the ways they are disciplined and evaluated. Raised in Rockland County, New York, Weingarten is a power broker in Democratic politics; her office overlooks the Capitol. The only openly gay union leader in the top ranks of organized labor, she lives in East Hampton, New York, and Washington, D.C.

In separate interviews ("If you can get them together, sell tickets!" says Richard Whitmire, author of The Bee Eater: Michelle Rhee Takes on the Nation's Worst School District), Rhee and Weingarten discussed education and each other.

Michelle Rhee: 'I'm Not Anti-Teacher'

Cornell Alumni Magazine: Your critics call you anti-teacher. Is that fair?

Michelle Rhee: I'm not anti-teacher. I love great teachers. I think great teachers are the solution to the problems we face today in lots of ways. But the question at the end of the day is, where should the protection sit? Should the protection sit with the adults or with the kids?

CAM: In D.C., did you communicate well enough with the good teachers?

MR: It is true that I didn't have consistent communication with good teachers. But the other thing is, the media take the juiciest things. So when I said we're going to move a lot of ineffective teachers out, even though I said it within the context of a lot of other stuff, that's the sound bite. I get it. That's my inexperience in not having been in the political realm. So, lesson learned.

CAM: Did you try to do too much, too soon?

MR: No. When you are leading the worst school district in the country, which is what we were considered when I got here, and 8 percent of your kids are on grade level in mathematics, you can't move fast enough. If you talk to political people, they all say, "You moved too fast." But if you talk to parents and kids—the people we were actually serving—they all said, "I'm not going to wait for eight years for the school system to get better. I need it to get better today because my kid is only going to be a first grader one time."

CAM: Do you regret posing for the cover of Time dressed in black and holding a broom?

MR: No—and I wear black 90 percent of the time. It's my color.

CAM: Some people thought the image implied that the people you were dealing with were dirt.

MR: That one I haven't heard. If there's anyone in the city that would have told me we didn't need to clean house and we didn't need sweeping reforms, I would have said, "You're crazy."

CAM: Of all the things you did, what worked best?

MR: We put in place a new framework that laid out for teachers, principals, and administrators what we think good teaching and learning looks like. We put a new evaluation system in place. Then, finally, there was the new teachers' union contract that essentially got rid of tenure, seniority, and lock-step pay, which I think were the three albatrosses around our necks.

CAM: What's the concept behind your new organization, Students First?

CAM: What's the concept behind your new organization, Students First?

MR: Education reform can't be top down. It has to be the very people who are being screwed by the system every day saying, "We won't take this anymore, something's got to change" and demanding something different. The education policy in this country over the last thirty years has been driven by special interests. You have teachers' unions, testing companies, you name it. There is no organized interest group that's advocating on behalf of kids to bring balance. So that was the whole idea.

CAM: What, specifically, will the organization do?

MR: We want to become one of the most powerful membership organizations in the country. We are going to focus at the state and local levels because that's where laws, regulations, and union contracts can be changed. And we are going to do that the old-fashioned way—people and money. Our goal is to raise $1 billion and have a million members within the first year.

CAM: It sounds like you want to build a National Rifle Association for education reform.

MR: I don't love the NRA. Let's say an AARP. Part of what makes the teachers' unions so powerful is that they have members paying dues. That's what gives them the financial heft they need to have influence. Our model is similar.

CAM: What are the most important things to fix in K-12 education?

MR: Students First is going to focus on three areas. One is on human capital. Second is on providing choice to families. Third is around fiscal responsibility and accountability.

CAM: What do you mean by human capital?

MR: The human capital stuff is probably what I'm most well known for. Everything we did in D.C. over three years often got synthesized to "she fired people." We did a lot more than that, but that was one thing that hadn't happened before in urban school districts, certainly not in D.C.

CAM: Why so much focus on teacher accountability?

MR: If you look at all the data and research, it says the in-school factor that has the most impact is the quality of the teacher who is in front of the students every day. Even for kids who are living in the most disadvantaged situations, having three highly effective teachers in a row can literally change their life trajectory. We're not saying that the home and environment factors don't matter. But if this is the factor that's going to have the most impact, then that is where we must have the greatest focus.

CAM: How do you improve teacher quality?

MR: We need to recognize the best people, pay them more, and move away from a pay system based on seniority. It is also important to be able to quickly move out the lowest performers. If you can't improve, we're not going to throw you in jail. You might still be a really good person—but you can't have the privilege of teaching our kids. There's just too much at stake.

CAM: Does Randi Weingarten of the AFT recognize the need for change?

CAM: Does Randi Weingarten of the AFT recognize the need for change?

MR: I think she does. She's in a tough spot because, on the one hand, she's getting a tremendous amount of pressure from President Obama, [Education Secretary] Arne Duncan, and people like me. But on the flip side there is a portion of the rank and file who want to hold on to those protections. This is not about the teachers' unions needing to change. The unions are doing what they're supposed to—protecting the privileges, priorities, and pay of their members. They're doing an excellent job of that.

CAM: That suggests they care more about their privileges and priorities than they care about students.

MR: But they should. In the automotive industry, the unions are supposed to look out for their people. The purpose of the union isn't to build a cheaper, faster, better car. That's not their job.

'We have lost our competitive spirit. We want to make kids feel good about themselves, so we are always praising and coddling them when they don't always deserve it.'CAM: When you announced Students First, Weingarten said we need more cooperation and less conflict in education.

MR: What I would say back to that is that the harmony we have been trying to create for two decades, where all the adults get along, has not helped our kids. We know that. We have some fundamental differences in what we believe, and we need to bring those to light and duke it out a bit.

CAM: What message should people take away from the movie Waiting for Superman? MR: One, that teachers matter a ton. You saw great teachers, and some not so great teachers, in that movie. But what I think the movie was trying to tell you is that great teachers are a huge part of the solution.

CAM: What about the parents?

MR: One of the most maddening things that I hear a lot is that if inner-city parents cared more about their kids, we wouldn't have these problems. Nope. In the movie you could tell every single one of them wanted the best for their kids. They were all willing to do whatever it took to get their kid into a great school, even if it meant waking up at five in the morning.

CAM: Is there a larger social problem with the American style of parenting?

MR: I think in this country we have lost our competitive spirit. We want to make kids feel good about themselves, so we are always praising and coddling them when they don't always deserve it. My kids play soccer. They suck at soccer, but they have all these medals and ribbons and trophies because we don't want them to feel bad about themselves. I juxtapose it with Korea, which is at the top of the charts in all the academic stuff. In Korea, when you start in kindergarten you get a rank in your class, one to forty. You know where you are, and you know how far you have to go to be Number One.

CAM: When you were at Cornell twenty years ago, could you have envisioned yourself becoming the face of public education reform in America?

MR: Absolutely not. I never planned on going into education. When I was in my senior year I started hearing about Teach for America. A few weeks before I graduated, I was trying to figure out whether I was going to go to graduate school in industrial and labor relations or do Teach for America. I was weighing the two, and my grandmother said, "Go teach."

CAM: And the rest is history.

MR: And the rest is history.