Flash forward more than forty years. In June, Oxford University Press published Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro, Perlman's follow-up to The Myth of Marginality. In the book, Perlman revisits the people and places she'd studied, using their stories as a lens through which she explores the favelas, Brazilian society, and urban poverty worldwide. In the intervening years, such squatter settlements—she never calls them slums, deriding the word as "an unfortunate throwback to an earlier period of class-based moralizing"—have mushroomed around the globe. They currently house half of all city dwellers in the developing world, a billion people in all. "She writes with compassion, artistry, and intelligence," Foreign Affairs said in its review of the book, which features an introduction by former Brazilian president Fernando Henrique Cardoso, "using stirring personal stories to illustrate larger points substantiated with statistical analysis."

When Perlman sought grant support for the follow-up studies, some funders turned her down on the grounds that after so many years, it would be impossible to track down more than a handful of her subjects; after all, for confidentiality reasons, she had neither addresses nor last names for her original interviewees. But those funders, she says, "didn't understand how much solidarity there was, and how many connections there were among people in these communities. They settled next to relatives or people from the same village, and they maintained and deepened those ties."

Over the course of two years, Perlman and her assistants painstakingly tracked down 41 percent of the original subjects, also interviewing their children and grandchildren—nearly 2,500 people in all. In the decades since her original study, she notes, prevailing wisdom about the settlements had evolved, though not entirely for the better. "It wasn't about dependency and marginality, but more that favelas were a trap—that society was so unequal that no one could get out and they must be in dead-end situations perpetuated from generation to generation," she says. "But I found that was not true. Only a third of the original interviewees were still in favelas. A third had been moved to public housing, and a third were in neighborhoods. And of the grandchildren, about 50 percent were living in legal neighborhoods in the formal city. They had moved out of the favelas and out of that stigma. That was a big shock."

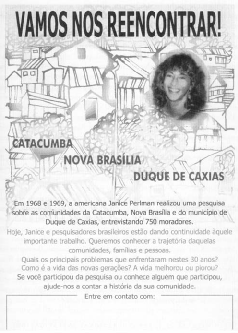

But for Perlman, the biggest shock of all was how the drug trade had altered life in many of the favelas, making residents afraid to come out of their homes and squelching their vibrant sense of community. "The fear that they were going to be removed and put in public housing had been replaced by the fear that they were going to be shot in the crossfire, in territorial wars between drug gangs or between gangs and the police," Perlman says. "It was wonderful to see the people I'd loved—but it was also terrifying to have young armed thugs at the entrances with semiautomatic rifles pointed at me, wanting to know what I was doing there." She had a particularly close shave in the Nova Brasília favela, where she snapped some photos of a corner she recognized from decades ago, unaware it had become a hotbed of the cocaine trade. "A cadre of heavily armed and angry kids surrounded me," she recalls. "I was able to give up my film and not my life, but it was very scary."

Favela was released to positive notices and a fair amount of media coverage, including a piece in the Economist and an interview on a New York City NPR station. Publishers Weekly gave it a coveted starred review. "Her measured approach is all the more compelling," it said, "because as she investigates the deprivation and danger faced by favela dwellers—19 percent of the city's population—she also conveys a deep understanding that favelas are not merely despair-filled slums but communities, and many residents have remained there by choice."

While Perlman formerly held a tenured professorship at the University of California, Berkeley, and has served on the faculty at Columbia and NYU, in recent years she's given up teaching to focus on advocating on behalf of impoverished city dwellers. She founded the Mega-Cities Project, a nonprofit that brings together community leaders from around the world to address problems facing urban areas. With events like a September book reading at the World Bank in Washington, D.C., she's working to spread the word about the rich culture of the favelas, lamenting the fact that many Americans see them solely as the setting of films about the violent drug trade, like the Oscar-nominated City of God. "I would like people to see the other side—the creative culture, the music, the dance, all that makes Rio and Brazil what they are," she says. "I want to show these brilliant, capable, and courageous people who are so often treated as invisible."