Great Migration

Reprinted from Favela: Four Decades of Living on the Edge in Rio de Janeiro (Oxford University Press). © 2010 by Oxford University Press.

In Favela, a political scientist recalls witnessing the shift from Brazil's rural villages to its urban squatter settlements

By Janice Perlman

The year I arrived in Arembepe was the very year that everything changed. Just like the miraculous arrival of ice in the fictional village of Macondo described by Gabriel García Márquez in One Hundred Years of Solitude, the transistor radio had appeared. It was the first time that most of the people heard directly about life beyond the parameters of their village. The technology that enabled music and messages, word images and information to be carried on airwaves into otherwise inaccessible places changed life options from that moment on. The opening of new horizons—for better or worse—beckoned people to the "bright lights, big city."

Young people were no longer content to spend their lives fishing, hoping to die in the arms of Yemanjá, the seductive goddess of the waters, or to work the land with the hoe, as their families had always done. They were attracted to the excitement of the unknown—they wanted to go where the ("movimento") action was. I could feel the magnetic pull that the city exerted on the youngsters and wondered what would happen to the newly arrived hopefuls if they got there, given their illiteracy and inexperience. It dawned on me that this was the beginning of an enormous sea change, one that would coincide with my own lifetime. As people became aware of broader horizons, there would be a massive migration from the countryside to the city—not only in Brazil but all over Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

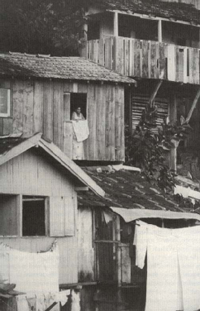

Years later, for my doctoral research, I followed the migratory flow from the interior state of Bahia and elsewhere in the Brazilian countryside to the big city of Rio de Janeiro. To find out where people went when they arrived in the city, I met the trucks bringing newcomers from the Northeast. These were open-backed flatbed trucks whose brightly painted and decorated sides were covered with mud and dust. They were called parrot's perches because of the way people sat jammed together on wooden slats laid around their perimeters and across the width of the truck bed. Some of the newcomers were met by relatives or people from their hometown who had arrived before. The rest were taken to a shelter until they could find someplace to stay. Most had sold all they owned to pay for the ticket to Rio and had no money at all for housing. The solution to their problem of finding shelter was to build shacks and eventually settlements on vacant lands, typically on steep hillsides, or morros, or in flood-prone swamps. Thus the favelas grew from tiny settlements into larger communities with distinctive personalities.

My initial research topic, "the impact of urban experience" on the new migrants, turned out to be a nonissue. The people adapted rapidly and astutely to the city and developed creative coping mechanisms to deal with the challenges they faced. The problem was that the city did not adapt to them. Rio had been the seat of the Portuguese empire during the Napoleonic wars, and it became the national capital when Brazil became a republic, in 1889. It was a citadel of the elite, the place where Brazil's large landowners, and later large industrialists, enjoyed their urban amenities. The streets were laid out following Haussmann's Paris, and the buildings were elegant. The favelas, as they grew, were seen as a blight on the urban landscape, a menace to public health, and a threat to urbane civility. The incoming migrants, and even those born in favelas, were seen as dangerous intruders.

From the beginning, I found the favelas visually more interesting and humanly more welcoming than the upper-middle-class neighborhoods. They could be seen as the precursors to the "new urbanism" with their high-density, low-rise architecture, featuring facades variously angled to catch a breeze or a view, and shade trees and shutters to keep them cool. The building materials were construction-site discards and scraps that would now be called "recycled materials." They were owner-designed, owner-built, and owner-occupied. And they followed the organic curves of the hillsides rather than a rigid grid pattern.

From the beginning, I found the favelas visually more interesting and humanly more welcoming than the upper-middle-class neighborhoods. They could be seen as the precursors to the "new urbanism" with their high-density, low-rise architecture, featuring facades variously angled to catch a breeze or a view, and shade trees and shutters to keep them cool. The building materials were construction-site discards and scraps that would now be called "recycled materials." They were owner-designed, owner-built, and owner-occupied. And they followed the organic curves of the hillsides rather than a rigid grid pattern.

The city's refusal to provide running water and electricity to these communities indeed created a danger to public health, but electrical connections were hooked into the power lines, and people took great pride in the cleanliness of their homes and persons. They were immaculate, despite the fact that all water for cleaning, cooking, and washing had to be carried from a slow-dripping communal standpipe along the road below. Women and children waited for hours and then hauled their water up the hillside in square five-gallon oil cans, sometimes set on a circular rolled-up cloth on their heads, sometimes hanging from both sides of a pole across the shoulders.

The migrants, rather than being the "dregs of the barrel"—the most impoverished among the rural people—were more often the "cream of the crop," the most farsighted, capable, and courageous members of their communities. They were the ones with the motivation and willingness to work in the least desirable jobs for the longest hours at the lowest pay in order to provide their children with opportunities they had never had. While in the eyes of others they were uprooted masses ready to rise up in revolt when confronted with the riches all around them, in their own eyes, they were proud of doing so much better than those who had stayed behind.

{mp3remote}http://www.podtrac.com/pts/redirect.mp3/audio.wnyc.org/lopate/lopate083010dpod.mp3{/mp3remote}

Janice Perlman Interview on WNYC (32:33)