Cynthia Marshall saved Evan Hubbard's life—but she did it third-hand. On Valentine's Day 2008, the former Marine sergeant donated a kidney to someone she'd never met, a Queens woman named Ana Maria Berdeja. Berdeja's husband, who had not been a donor match for his wife, gave a kidney to Rubina Parvin, a Long Island City homemaker originally from Bangladesh.

Cynthia Marshall saved Evan Hubbard's life—but she did it third-hand. On Valentine's Day 2008, the former Marine sergeant donated a kidney to someone she'd never met, a Queens woman named Ana Maria Berdeja. Berdeja's husband, who had not been a donor match for his wife, gave a kidney to Rubina Parvin, a Long Island City homemaker originally from Bangladesh.

A novel 'chain' system for kidney donation, pioneered at Weill Cornell, is giving patients a new chance at life

By Beth Saulnier

Cynthia Marshall saved Evan Hubbard's life—but she did it third-hand. On Valentine's Day 2008, the former Marine sergeant donated a kidney to someone she'd never met, a Queens woman named Ana Maria Berdeja. Berdeja's husband, who had not been a donor match for his wife, gave a kidney to Rubina Parvin, a Long Island City homemaker originally from Bangladesh. Parvin's husband, in turn, gave a kidney to five-year-old Evan, who had been severely ill for most of his young life. "Cindy Marshall is the best—God bless her," says Mohammed Islam, Parvin's husband and Evan's donor. "Without her, we could not do any of this. Donating is a wonderful thing. I understand how people suffer, because my wife suffered so much."

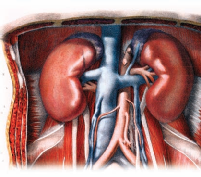

It's called a Never Ending Altruistic Donor (NEAD) chain— a sophisticated medical take on the bucket brigade, or perhaps the childhood game of "telephone." In NEAD, a person willing to donate a kidney to a stranger begins a chain that, in theory, is open-ended, with each link representing a life saved. NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center (NYPH/ WCMC)—along with its nephrology partner, the Rogosin Institute—was among the first institutions to pursue the chain system, and remains one of about a dozen where it's performed. "The bottom line is that there are far more people in need of a kidney transplant than there are organs available," says Sandip Kapur, MD '90, chief of transplant surgery at NYPH/WCMC and a professor of surgery at Weill Cornell. "In the past few years, we've tried to explore all options for transplants to go forward, and the exchange-type transplant is one example of that."

With more than 75,000 Americans awaiting kidney transplants, physician-scientists have been exploring new ways to make more organs available—for example, using immune therapy to precondition a recipient's body to accept an organ it might otherwise reject, and developing guidelines that allow organs to be harvested after cardiac death as well as brain death. NEAD is another weapon in that arsenal, addressing a fundamental fact of organ donation: while many people languish on waiting lists, a significant portion of them have a willing donor who is not a medical match. NEAD allows such donors, in effect, to rescue their loved ones by proxy. "It's awesome," Evan's mother, Nina Hubbard, says of the chain concept. "By giving a kidney, you're saving a life and making the world a better place. Some people I've spoken to outside the hospital hesitate because you have to donate a kidney but it's not going to go to your loved one. But that's something nobody should be afraid of because, in a sense, you're saving your loved one—you're just doing it through someone else."

Sometimes the donations are done in pairs, with two donor-recipient couples being matched with each other. But if an altruistic donor like Marshall steps forward—the rare person who is willing to donate a kidney to a stranger—it can form the first link in an open-ended chain. Due to the complexity of matching several donors and recipients, and the logistics of scheduling simultaneous operations, each segment of the chain tends to comprise no more than three transplants in a single day. "Because there was that initial altruistic donor, a person we don't owe a kidney to, there is at the end a bridge donor, who is a donor who hasn't given yet," says David Serur, Rogosin's medical director and a Weill Cornell professor of clinical medicine. "There are four donors and three recipients, so there is one donor at the end who will initiate another cluster of transplants."

Marshall first started thinking about donating twelve years ago, when her husband gave a kidney to his brother, whose own had failed due to diabetes. A former radio repairwoman in the Marine Corps, the fifty-one-year-old Marshall now lives in Twentynine Palms, California, and works as a civilian financial specialist at the Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center. "It's just something I've always wanted to do," she says of donating. "Living close to it in the family and seeing how well my brother-in-law did after the surgery—and he wasn't expected to live long on dialysis—was my motivation. I thought if I could do that for somebody else, and it wasn't going to physically affect me in the long run, why wouldn't I?"

But back when her husband donated, the idea of altruistic donation was practically anathema. For one thing, conventional wisdom held that no one of sound mind would offer a kidney to a complete stranger. Then, in late 2007, Marshall saw a TV program that mentioned the increased acceptance of altruistic donors. The shift, in part, was due to the fact that the kidney removal surgery had become much less invasive. Before the advent of laparoscopic surgery, donation required an operation called an open nephrectomy, which entailed extensive recovery time and left patients with a scar vaguely resembling a shark bite. "The advent of minimally invasive surgery has made the process of donating a kidney much more palatable," Kapur says. "It's not associated with the same sort of morbidity that the big open operation used to have, where it would incapacitate someone and have him or her in the hospital for ten days and a full three months of recovery, and it would have a huge impact on their lives and jobs. Now, using minimally invasive techniques, patients go home the next day or the day after. Generally if they have a desk job, they're back to work in three weeks."

Like all donors, Marshall underwent a battery of tests to ensure she was healthy enough to donate. They include blood tests to evaluate kidney and liver function, imaging to confirm the existence of two healthy kidneys, and a twenty-four-hour urine-collection test to see if the kidneys are working well. But unlike those donating to a close relative, altruistic donors must pass stringent psychological tests as well. "A mother giving to a child doesn't usually need a psychiatrist," Serur says. "But for altruistic donors coming out of nowhere, we want to make sure they're OK, that they're not wacko—and sometimes they are. We want to be sure that they are doing it for the right reasons. The social worker has to make sure that they have a stable support system, that there aren't any people in their family who are against this and could be a cause of stress, that the donor has access to medical care, and that they have insurance. We want to make sure they have all of that in place before they go forward."

One "wrong" reason for donating, of course, is financial gain; it's illegal to sell an organ in the U.S. Other misplaced motives can range from the odd to the overly idealistic. "Somebody saying, 'It would please my mother if I donated' would be a wrong reason," Serur says. "Or, for another example, 'I want to bring peace to the world by donating a kidney.' These are things that are not necessarily insane but are a little far-fetched. We want to make sure they're doing it for the right reasons; that is, 'I want to help somebody' or 'I want to be a part of starting a chain and help more than one person.' Often, we've figured out that those who are sincere have a history of volunteering parts of their bodies. They've donated blood, platelets, or even bone marrow."

There are, in essence, two tracks for patients awaiting a kidney: one for those who have a willing donor, and another for those who must wait for a cadaveric donor. But a subset of patients have a willing donor who is not a medical match; for them, transplant swaps—in which two sets of donors and recipients are paired up—and donor chains offer a novel solution. However, as in a conventional live donation, each recipient must bring a donor to the table to participate in the process. "We need to make it fair in some way, and this is an ethical dilemma that we face," Kapur says. "The other way to look at it is this: there are a lot of people on the waiting list who are disadvantaged because they don't have a donor. But that would exist whether the chains did or not."

The living donor track is preferable not only because it cuts wait time; organs from living donors versus cadavers also last longer, an average of fifteen years compared to ten. "That's an important difference," says Serur. "If you're sixty years old and you're getting a living kidney, you likely will never need another one. But if it is only going to last ten years, you're probably going to need another one. So not only do living kidneys last longer, but there's less of a need, because fewer people will require second kidneys."

Why do living donor kidneys have 50 percent more longevity? Part of the answer is timing. Organs from live donors, which are removed during scheduled surgeries, are generally out of the body for only thirty minutes before being transplanted. "When we get a kidney from someone who died, that organ is outside the body, without a blood supply, for up to twenty-four hours," Serur says. "That does do some harm to the kidney. It's amazing that it works at all." Another reason that live-donor organs last longer is the simple fact that, by definition, the cadaveric donor's body has died, with all the damage that entails. "Something traumatic has happened to these people," Serur says. "It's usually a stroke, a gunshot wound to the head, or a motor vehicle accident. That can affect kidney function. But a living donor organ is coming from a healthy, live person."

At Rogosin, both sides of the donation equation have their own nurse-advocate—Marian Charlton for donors, Judith Hambleton for recipients—and the process is kept entirely separate to ensure there are no conflicts of interest. "As long as I've been here—and I've been employed here since 1997—we have always had separate teams, and that includes a social worker, nurse coordinator, nephrologist, and surgeon," Hambleton says. "So, never the two will meet. That way there is full objectivity." Hambleton notes that for a variety of reasons, not every person who comes through the door actually wants to donate. "It's sometimes an indistinct line. For example, a family member may feel obligated, but deep down really doesn't want to, and it's the job of the donor team to weed out those people." Some potential donors will even confide that although they don't want to donate, they feel they have no choice due to family pressure. "If absolutely necessary," Hambleton says, "the donor team will give people a medical out, so they don't feel external pressure to do it if their heart isn't in it."

Marshall is a longtime blood donor and has signed up with the national marrow registry as well. She passed the psychological testing easily and was flown to New York at the expense of the National Kidney Registry, a nonprofit established in 2007 by a wealthy businessman who tried to donate to his daughter but was not a medical match. Marshall donated her left kidney on a Thursday and was discharged Friday evening. A week later, in an emotionally charged press conference at NYPH/WCMC, she met her recipient—Berdeja, a fifty-eight-year-old born in Bolivia, who had been on dialysis for three years and suffers from diabetes, lupus, and high blood pressure. "It was very special for me to meet her," Marshall says. "It was a great experience, and very strange. There was this little part of me standing over there."

The same press conference unveiled the other links in the chain; hospital officials called their names one by one, uniting donors and recipients amid a flurry of tears. Islam, an observant Muslim who sells incense on Queensborough Plaza, already had an inkling of where his organ had gone. "When the surgery was finished, that night I dreamed that my mother told me, 'You did a good thing. You saved somebody's life. It is a little five-year-old boy, and God loves you.'" At the press conference, though, it took a few moments before he realized his name was being called as Evan's donor. "When I stood up, Nina hugged me and cried, cried, cried," Islam says. "I feel like Evan is my son, like he is part of my body. Yes, he is part of my body."

Marshall stayed in New York for ten days for follow-up care before going home to California. The scars from three nickelsized incisions where the guiding instruments were inserted have faded to almost nothing, she says, and the longer one where the kidney was removed is barely noticeable. She doesn't need to take any special medications or alter her diet; all in all, she says, giving up a kidney hasn't affected her in any meaningful way. "They just told me I can't kickbox or play football—but that wasn't a problem because I never did them," Marshall says with a laugh. "They don't want you to injure the remaining kidney, so if I engage in sports I have to wear sufficient padding." Marshall calls the donation "one of the best decisions I've ever made," which Charlton says is a common sentiment among donors. "We see most people at a couple of months post-op, at six months, a year, and I always ask that question: 'Any regrets?' And I have yet to have anyone say that they regret doing it, even if the recipient isn't doing so well."

Marshall was at one end of the Valentine's Day transplant chain; at the other was little Evan Hubbard. Evan had been ill for nearly four years—ever since the morning when, at eighteen months, his mother glanced down into his crib and noticed that something was wrong. "He looked swollen, like his legs were bigger," says Nina Hubbard. "I said maybe it's allergies, because I have bad allergies and his dad has food allergies. We thought we could give him a little Benadryl and it would go away. But the next morning when we woke up he was heavy. When I went to pick him up out of his crib, I had to use more strength than normal."

They brought the boy to his pediatrician, and eventually to a specialist who diagnosed nephrotic syndrome. The intervening years were a blur of medications, doctor visits, and rounds of at-home peritoneal dialysis before physicians decided he needed a transplant. "When it came time for Evan to receive his kidney transplant, my husband and I said, 'One of us will give it to him and we'll be OK,'" Hubbard says. "But we found out we were not a match, and of course we were devastated. I stopped breathing. I had to regroup. Because as a mom and dad you want to be able to help your child, and we were not able to help him."

Since receiving Islam's kidney, Evan has made a strong recovery; he attends first grade at the East Village Community School in Manhattan, and on October 16 he celebrated his sixth birthday. "Evan has much more energy than he did before," says Hubbard. "He's still on medication, but not as much, and he's not swelling at all, no diarrhea, no vomiting, no fever. Now he's jumping around, he's happier. He's very active. He tells me, 'Mommy, I'm not sick anymore. I feel good.' And that's what I live on now."

In May, Evan's father—a longtime billing clerk at NYPH/ WCMC—donated a kidney to a Queens man whose brother, in turn, gave one to a Connecticut woman; her husband will be the initial donor for the next group of transplants. "My husband was able to donate to Evan in a roundabout way, because the next person received a kidney," Hubbard says. "And God forbid, down the line, if he needs another transplant, I will do it."

Getting Better

NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center has long been in the vanguard of kidney transplantation. The first such surgery in New York State was performed there in 1963, and the program has since grown to be one of the biggest and busiest in the country, doing more than 225 transplants a year; in summer 2007, NYPH/WCMC and its nephrology partner, the Rogosin Institute, announced that they had performed their 3,000th transplant. "Transplant in itself is not a very old field in medicine," says Sandip Kapur, MD '90, the hospital's chief of transplant surgery. "The first successful transplant was only in 1954. During that time period there were a number of years where the results weren't great, and they only got very good in the Nineties." The national Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network keeps a running tally of the number of people on waiting lists, available online at www.optn.org/data; as of late October, about 100,000 people were waiting for organs, 78,000 of them kidneys.

New drugs and surgeries have improved the odds of survival When the first kidney was successfully transplanted in the U.S. a half-century ago—a donation from one twin brother to another—the odds of surviving a year after a living-donor transplant were just 10 percent; today that figure is 90 percent. The vastly improved survival rates are due in part to new generations of anti-rejection drugs, but also to the advent of minimally invasive surgical techniques that have allowed for more living-donor transplants, and from a wider variety of donors. "It has allowed us to look at donors much older than we normally would have," says Kapur. "We use donors in their seventies now. Before the advent of minimally invasive surgery, we wouldn't have even contemplated that." The new surgical techniques, he says, "have been a major contributor to making living donation more acceptable. And there's also been a tremendous amount of media attention about people needing a kidney transplant, and the fact that the results of transplantation are so excellent."

When the first kidney was successfully transplanted in the U.S. a half-century ago—a donation from one twin brother to another—the odds of surviving a year after a living-donor transplant were just 10 percent; today that figure is 90 percent. The vastly improved survival rates are due in part to new generations of anti-rejection drugs, but also to the advent of minimally invasive surgical techniques that have allowed for more living-donor transplants, and from a wider variety of donors. "It has allowed us to look at donors much older than we normally would have," says Kapur. "We use donors in their seventies now. Before the advent of minimally invasive surgery, we wouldn't have even contemplated that." The new surgical techniques, he says, "have been a major contributor to making living donation more acceptable. And there's also been a tremendous amount of media attention about people needing a kidney transplant, and the fact that the results of transplantation are so excellent."