This is Philip Messina's challenge: to create a world. More specifically, he must craft a universe comprising exotic creatures, supernatural spirits, and four distinct human cultures—the Water Tribes, the Earth Kingdom, the Air Nomads, and the Fire Nation.

This is Philip Messina's challenge: to create a world. More specifically, he must craft a universe comprising exotic creatures, supernatural spirits, and four distinct human cultures—the Water Tribes, the Earth Kingdom, the Air Nomads, and the Fire Nation.

From postwar Berlin to the Vegas strip, production designer Philip Messina '88, BArch '90, makes movie magic

By Brad Herzog

This is Philip Messina's challenge: to create a world.

More specifically, he must craft a universe comprising exotic creatures, supernatural spirits, and four distinct human cultures—the Water Tribes, the Earth Kingdom, the Air Nomads, and the Fire Nation. He has to make it epic yet accessible, unprecedented yet familiar, fantastic yet plausible. And as the production designer for Paramount Pictures' The Last Airbender, he has to keep to a budget.

Scheduled for a summer 2010 release, The Last Airbender is a live-action version of an Emmy-winning animated series that aired on Nickelodeon for three seasons. The movie covers the TV program's first season, but with a big budget and a big-name director (M. Night Shyamalan), the studio has a trilogy in mind. Set in an Asian-influenced universe where martial arts coexist with manipulation of the elements, the story follows the adventures of a boy named Aang, a successor to a long line of Avatars. Aang would be twelve years old, except that he was frozen in an iceberg for a century. After being rescued, he must stop the warlike Fire Nation from enslaving the people of the Water, Earth, and Air.

The jury is out on who has the tougher assignment—Aang or Messina.

What an illustrator is to a book, a production designer is to a film. He or she is part of the primary creative team—along with the director, cinematographer, and costume designer—that translates the words in a screenplay into the images on the screen. As head of a film's art department, the production designer oversees the art director, assistant art directors, set decorator, illustrators, prop masters, location scouts—essentially, everyone who determines the look of the movie.

It is late spring, still a year before filming will even begin, but Messina '88, BArch '90, is already immersed in pre-production. He is working in temporary offices at Culver Studios in Culver City, California; the space is devoid of decoration except for the concept illustrations that line the walls. Among these illustrations—part photograph and part computer-generated fantasy, "an amalgam of real and fake," Messina says—are depictions of a fortified city teeming with waterfalls, an ice-bound village atop frozen tundra, a fire ship inspired by Victorian Age machinery, and a temple that seems to hang from the sky. "This is like four period films," says Messina, as a handful of his production illustrators sit in adjacent rooms, tinkering with images on their computer screens. "I think of it as period because there's a primitiveness to it. But we also have to put our own spin on it, and they all have to feel like the same world in the end."

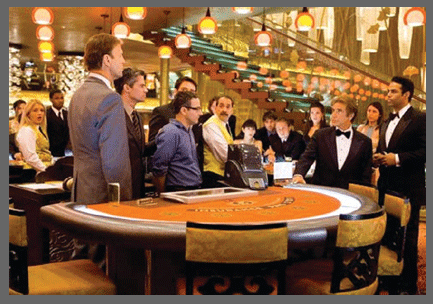

It is a challenge that Messina was eager to take on. His agent sends him many scripts, but he is most tempted by projects that are new and different. Ironically, he often achieves that goal by working with the same director—Oscar-winner Steven Soderbergh. For Soderbergh's sci-fi film Solaris, Messina oversaw construction of a multi-level space station on a Warner Brothers soundstage. For The Good German, made in the style of Forties film noir, he was charged with turning a Universal Studios back-lot into postwar Berlin. ("It was the only movie I've ever worked on where at the end I still wanted to do more," he says. "Usually you're fried and exhausted, and you just want to go sit on a beach.") And for Ocean's Thirteen, Messina had to construct a working casino that was, per Soderbergh's instructions, "beautiful, but in a mad way." Says Messina: "I had about $15 million in my construction budget. In architecture, you can do a pretty great building for fifteen million bucks, but it was amazing how quickly it went."

On one of the largest soundstages in L.A., Messina oversaw creation of a tri-level casino, which included a working elevator, hundreds of slot machines, thirty-two gaming tables, and two restaurant-bars. Over the craps tables he hung a 9,000-pound chandelier made of hand-blown Austrian glass that arrived in ten packing crates and took five people a week to install. (Variety described the set as "dominated by sumptuous golds and reds, with money dripping from every frame"; according to the New York Times, "America's playground has never looked so glamorous and seductive.") Along with the big picture, Messina also paid careful attention to the smallest details: the casino's logo was on each table, chip, and die. But as meticulously planned as his designs are, no finished set is ever quite what he originally conceived. "I can never picture all the nuts and bolts," he says. "And sometimes there's a happy accident on the set, and we'll use it. I try to keep the process as fluid as possible, but at some point you have to make decisions and stick to them."

Although Messina wasn't much of a film buff while growing up just north of Boston, he did dream of being an artist—but his parents believed his math skills would be put to better use as an engineer. After graduating from prep school, Messina settled on a compromise of sorts and enrolled in the Architecture college. "By about my fourth year, I convinced myself that I was not going to be an architect. I actually failed a semester of design because I decided I was going to be an actor," he says with a laugh. Although he did appear in a production at Risley Hall, he also managed to earn his degree.

After graduation, he took a job as a private investigator— even tailing people while investigating divorce and worker's comp cases. He then worked as a carpenter on an exhibit at the Boston Center for the Arts, and later as the center's liaison to architects and developers. Finally, the phone rang with the kind of life-altering offer more commonly found on the big screen. A production designer needed some help on Mermaids, a movie filming in Boston. The comedy-drama followed the adventures of a single mother (Cher, in her first role after winning an Oscar for Moonstruck) and her daughters (Winona Ryder and Christina Ricci) in the early Sixties. Messina was hired to make a few models and wound up designing much of the period set. "It fell into my lap," he says. "I didn't even know this kind of job existed. But I got paid well, and I thought, Wow, I want to do this."

For Ocean's Thirteen, Messina had to construct a casino that was 'beautiful, but in a mad way.' Says Messina: 'In architecture, you can do a pretty great building for $15 million, but it was amazing how quickly it went.'After a few more years in Boston—designing sets for movies like School Ties and Housesitter—Messina married his longtime girlfriend, Kristen Toscano '89, and they moved to Los Angeles. (A set decorator who studied at Cornell for a semester before transferring to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Toscano has collaborated on all the films that Messina has designed—except for The Last Airbender, because she is focusing her attention on their first child, son Luca, born last July. "One of the most difficult things about working for my husband and best friend," she says, "is not being able to go home at the end of a difficult day and vent about my boss.")

Messina served as an art director on ten movies—from Ed and His Dead Mother to Shyamalan's The Sixth Sense—before finally earning screen credit as production designer on Soderbergh's Erin Brockovich. He and Soderbergh have collaborated on seven films since, including Traffic (for which Soderbergh won a Best Director Oscar) and all three Ocean's movies. All have required lengthy commitments, but Messina notes that—compared with the field in which he earned his degree—film offers near-instant gratification. "The time frame on architecture is years. Usually, you can be in and out of a movie in six months, starting with an empty stage and ending with an empty stage," says Messina, who has also designed TV commercials for clients ranging from Mercedes to match.com.

Messina approaches each project primarily as an artist, but also as an accountant. He starts by reading the screenplay several times and gathering images that supplement the storytelling— photographs, paintings, anything to capture the mood and aesthetic of the film. But his biggest decision, made with the director and producers, concerns where to shoot the movie. Should the sets be built on a soundstage, shot on location, or both? This is determined by a number of factors, including the budget, the shooting schedule, and the script itself. For instance, thirty-two pages of the Erin Brockovich screenplay—nearly one-fourth of the movie—were scripted to take place in a law office, so Messina constructed it on a soundstage so he could better control the environment.

When selecting a location, Messina has to ask himself the obvious questions about whether it will work visually and financially. But there are also countless smaller issues. Is the location too noisy for dialogue? Is there sufficient access for trucks and trailers? Is there enough room to lay a set of tracks so the camera can be mounted on a moving dolly? Will they be able to control the lighting? Where's the sun?

The opening scenes of The Last Airbender take place on a vast ice plain. So Messina and a location manager trekked to Greenland last March and spent nearly a week scouting out a seaside location, where they planned to construct a tiny village. It met their visual specifications, but there were other considerations—logistics and contingencies, for instance. The site is located just outside Greenland's third-most populous settlement, Ilulissat, making transportation more practical in a place where most people travel by dog sled, boat, or helicopter. And the city has an athletic facility, where Messina plans to construct the interior of an igloo in case bad weather forces them to cut short their use of the outdoor set. The filmmakers want to shoot in Greenland for no more than two weeks, and any extra time spent reaching the location or waiting for the weather to change would set back the schedule.

But it isn't always the story that dictates Messina's locations; sometimes it's the other way around. The movie 8 Mile, directed by Curtis Hanson, features rapper Eminem, but its real star is Detroit. Messina spent a few weeks scouting the city, and among the locations he found was the Michigan Theater, a seventy-five-year-old movie house that had been gutted, its main hall and lobby converted into a remarkably ornate yet decaying parking structure. He told Hanson, "I don't know what this could be used for, but you have to see it." Hanson wound up rewriting a key scene—a spontaneous rap battle in which Eminem's character first demonstrates his skills—to fit the location.

The opening scenes of The Last Airbender take place on a vast ice plain—so Messina and a location manager trekked to Greenland.Occasionally, a design element that Messina liked but was unable to use in one movie will find its way into another. For The Last Airbender it was a nearly forgotten piece of set dressing that became an inspiration. Charged with creating the air temples—ethereal castles on mountaintops—Messina couldn't come up with a suitable design. He knew he wanted a hint of Tibetan architecture in the building, but he went through several iterations, none of which satisfied Shyamalan. "We talked about the nature of it, what it should evoke, the philosophy of the people behind it," says Messina. "Their element is air. How does air translate into a building? You can go fifty different ways with it." But then one of Messina's assistants found a photograph of an unused prop—an exotic-looking lamp that was originally supposed to be part of the quasi-Asian-themed casino lobby in Ocean's Thirteen. Messina used it as a starting point for his design, and an air temple was born. "It's interesting that the same piece of research could be used in the lobby of a modern building or in something that's supposed to be thousands of years old," he says. "That's the fun of what we do."

Messina's philosophy is that the big picture can be influenced by the smallest details. One of the final scenes of Erin Brock-ovich shows the title character's boss (Albert Finney) talking on the phone, triumphant after winning an enormous lawsuit. Without telling the actor or director, Messina printed a mock issue of a legal magazine—with Finney's character smiling on the cover— and placed it on the office desk. Soderbergh loved it and wound up starting the scene with a close-up of the cover, complete with the headline GOLIATH BEWARE. "It's fantastic when you have that kind of direct effect," Messina says. "The more detail you bring into it, the more fully fleshed out it is. Half the time the camera doesn't even see that stuff, but the day the camera lands on that one piece, you want to have the right thing there."

Messina even went so far as to affix a fake mailing label to the magazine, the kind of detail he often adds to inject another layer of realism. When a scene is filmed in a bedroom or kitchen, he will sometimes fill the closets or refrigerator with the kind of items that the character would have there—just in case, says Messina, "the actor suddenly wants to open a cabinet."

Brad Herzog '90 will publish his latest travel memoir in May. Greek to Me chronicles his Odyssey-themed, cross-country road trip to Ithaca for his 15th Reunion.