I might've been done for the day, but Obama wasn't. While he raised the roof delivering his stump speech, I walked off the arena floor and into an outer lobby, looking for a corner that might shield enough of the noise so I could call my wife. I checked in with Stina twice a day, bare minimum, once when she woke up and again just before she went to bed, and tried to catch her several other times so I could talk to our three kids as well. I could tell from the four rings before she picked up, and her sleepy voice once she did, that she'd fallen asleep reading to Bobby, our four-year-old.

"Hi, honey," she said, her voice trailing off. She sounded so worn-out. Sure she was tired of raising three kids alone, with me gone for months at a time, but this was more than fatigue. She was worried. This had nothing to do with her husband's new bosses and a change in his professional standing. In the eight years since my father died, she'd watched me head off to cover two wars, suffer enough post-traumatic stress to require several months of therapy, then allow my unrestrained ambition to lead me to an intensely demanding job at the White House. Until his death we'd been walking a path together, holding hands. Then suddenly I'd dropped hers and veered off into some thick woods, chasing something I couldn't catch. The easy joy Stina had always found as a wife and mother had started to leach from her home.

"That's okay, Stina," I told her. "Back to sleep. I'll talk to you in the morning. Love you." I hung up feeling hollow and detached. The balancing act I'd worked out long ago between my scampering up the career ladder and remaining connected to my wife and kids had started to feel badly outdated.

Wandering back into the arena, I climbed the stairs up to the media riser, pulled out my BlackBerry, and scrolled down to Dave's e-mail. I hit Open and saw a chart:

| YEAR | FIRST NAME | LAST NAME | AGE | TIME |

| 1980 | ROB | AXE | 44 | 3:42:43 |

| ERT | LRO | |||

| D | ||||

| 1981 | ROB | AXE | 45 | 3:39:53 |

| ERT | LRO | |||

| D | ||||

| 1982 | ROB | AXE | 46 | 3:29:58 |

| ERT | LRO | |||

| D |

It took a moment for me to realize what I was looking at, and just a split second more for my nose to wrinkle and my eyes to fill. Dave, who loved to tool around on the Web, panning for whatever nuggets he could find from our pasts, had found my father's race times for the three New York City Marathons he'd run in the early 1980s.

The tears were no surprise. I'm a world-class weeper. Since she was five, my daughter, Emma, has proudly declared, "My dad cries more than most men." Funerals and weddings are for amateurs. I've lost it at the end of Charlotte's Web. But nothing brings the tears more reliably than thinking about my dad.

His was one of those deaths that left everyone shaking their heads and scared the hell out of the men in the neighborhood. Never mind the three marathons he'd run in his forties. He'd eaten right and hadn't been much of a drinker. His parents had been ninety-one and eighty-nine at his funeral. And my mom was a health-food nut who'd made my dad the first guy on the block to mix wheat germ into his yogurt. He bubbled over with vigor. If they could've figured out a way to harness his energy, he could've lit Cleveland for a decade. All that, and he'd died at the age of sixty-three in January 2000, following a nine-year battle with prostate cancer.

I put the BlackBerry back in its holster and watched Obama finish his stump speech. "Yes we can. Yes we can. Yes we can, Houston." The electrified crowd didn't want to go anywhere, but after ten minutes, they realized he wasn't coming back onstage. The houselights went up, and the arena began to clear.

Wanting to look at my dad's race times again, I climbed down off the riser and found a dull-brown metal folding chair, collapsed and leaning against a wall. I grabbed it, unfolded it, and sat down, rocking slightly back and forth with my Black-Berry extended at arm's length to accommodate my rapidly deteriorating vision, which I'd been refusing to acknowledge.

"Okay, let's see here, he ran 3:39:53 when he was forty-five."

I was whispering to myself, lips barely moving, as I went from column to column, performing calculations.

"He ran 3:39:53 when he was forty-five," I repeated, digesting what I was seeing. My mind raced to the next set of numbers. "Then 3:29:58, when he was forty-six." That stopped me for half a second. I remembered my dad telling me, when I was a kid and he was in the middle of his marathon years, that breaking 3:30 was a big deal. Going sub-3:30 meant running a little more than twenty-six miles at eight minutes per mile, an impressive pace.

"He broke 3:30 when he was forty-six," I continued to myself.

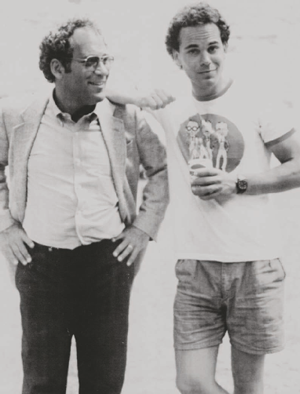

I sat and rocked for half a minute more, thinking of the framed photograph hanging in the front hallway of our home in the Washington, D.C., suburb of Chevy Chase, Maryland. There was my father, enraptured, crossing the finish line of one of those marathons, his arms thrusting straight up in triumph. I could use some of that. His body may have been exhausted, but his eyes were dancing. A running magazine had published it, clearly looking to inspire.

"I'd need at least a year."

I'd never run a marathon, but I'd watched my dad as he planned his training, beginning a year before the race. I knew the kind of dedication required just to finish a marathon, never mind to run one in eight-minute miles. The old man was already in top shape when he did it, having run steadily for four years before he took on the challenge. I didn't even pause—

"I could do this."

—which was slightly delusional, given that I was in the worst shape of my life, flabby in every imaginable way. Without much of a fight, I'd surrendered to the grind of the campaign trail, dismissing the thought of exercise as an indulgence the long hours didn't permit. At that moment, leaning forward in that brown metal chair, elbows on my knees, BlackBerry in my hands, belly drooping over my belt and sagging toward the floor, I couldn't run around the block.

"It might be just what I need."

I knew the New York City Marathon was always run in late October or early November. In other words, right around Election Day. No way, especially if Hillary won the nomination. But 2009 was a definite possibility. I'd be forty-six years old. My dad's age when he ran his last New York City Marathon would be my age running my first.

"Twenty-one months. I could do that."

I tried to slow myself down to take full measure of what I was contemplating. But I couldn't. My very next thought was on me in a heartbeat. It wasn't a choice. It was instinct. There was nothing conscious about it.

"I bet I can run it faster than he did."

Jim Axelrod '85, a national correspondent for CBS News, previously served as chief White House correspondent.

EXCERPTED FROM IN THE LONG RUN: A FATHER, A SON, AND UNINTENTIONAL LESSONS IN HAPPINESS BY JIM AXELROD, PUBLISHED IN MAY BY FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX LLC . COPYRIGHT © 2011 BY JIM AXELROD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.