Portrait of Anna ComstockRobert Barker

When Anna Botsford Comstock 1885 died in summer 1930 at the age of seventy-five, the pioneering naturalist left behind not only an ailing husband—famed entomologist John Henry Comstock 1874, who was severely debilitated by a series of strokes and would pass away just half a year later—but a 760-page manuscript chronicling their decades of marriage, travel, teaching, and scientific study. It would be nearly a quarter-century until that memoir reached a wide readership, in the form of a book compiled by Glenn Herrick 1896, Anna’s second cousin and the couple’s closest living relative.

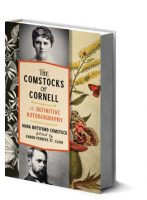

Published in 1953 by a division of Cornell University Press, The Comstocks of Cornell was in fact just part of Anna’s original manuscript. It had been heavily edited by Herrick, also a professor of entomology on the Hill—not only to de-emphasize events and characters he considered irrelevant, but to streamline the language, remove any hint of controversy, and shift the focus toward John Henry’s august accomplishments, including his role as founder of Cornell’s entomology department.

But this spring, CU Press is publishing a new edition of The Comstocks of Cornell—a version that comprises Anna’s entire manuscript, or at least the 716 pages that survive. It’s edited by Karen Penders St. Clair, PhD ’17, a former laboratory staffer in CALS and the Vet college who undertook the project as her doctoral thesis in horticulture, devoting six years to research in Kroch Library’s Rare and Manuscript Collections, home to the Comstocks’ papers. Currently an independent scholar based in Rochester, New York, St. Clair hopes the upcoming volume will give readers a better sense of what Anna was truly like, beyond the familiar tropes of her status as Cornell’s first female professor, a leading scientific illustrator, and an early advocate of nature education. “She was sassy. She was a romantic. She had a fantastic vocabulary. She was opinionated,” says St. Clair. “And you wouldn’t know any of that from reading the 1953 book.”

Born in a small town in Western New York, Anna Botsford grew up on the family farm, with parents who supported her love of learning; aiming for a university education, she did college prep work at a nearby women’s school. “An outstanding student,” notes her entry in The 100 Most Notable Cornellians, “Anna delivered the salutatorian address to her class in Latin, as was customary.” She matriculated on the Hill in 1874, one of thirty-seven female students (compared with 484 males) who lived off campus in advance of the completion of the Sage College women’s residence. “The cold-shouldering of the females by the males existed from the first,” Morris Bishop 1914, PhD ’26, writes in A History of Cornell—going on to note that while Anna had been warned before coming to campus that male students paid co-eds little attention, that didn’t prove to be her experience. “She was a very intelligent person, original, decided, and humorous, and beautiful even in her old age,” Bishop writes. “In college, she had no awareness of ostracism; indeed, she had to discourage men callers.”

One of Anna’s etchingsAlamy

Anna left Cornell after two years—as St. Clair explains, moving back home in the wake of breaking off an engagement to a classmate. She returned to campus in 1878, not as an undergraduate but as the new wife of John Henry; six years her senior, he had taught a course she’d taken in zoology, and the two became close friends before their relationship turned romantic. (“The Comstock partnership, in science and life, vindicated Andrew D. White’s judgment of college attachments and their results,” Bishop notes, referring to the founder’s belief that for young people, studying together was a far better way to find a compatible mate than conventional courtship.) Anna eventually completed a BS in natural history and—having a lifelong talent for painting and drawing—became a skilled illustrator of insects and plants, initially to help her husband with his lectures and publications.

Her career as a nature educator began in earnest in the 1890s, when she joined a New York State committee aimed at encouraging rural youth to stay on their family farms by teaching them to appreciate the wonders of the natural world. “The state legislature appropriated funds for Cornell’s College of Agriculture to implement a pilot project,” says Notable Cornellians. “Liberty Hyde Bailey, Cornell’s distinguished horticulturalist, was named head of the ‘nature study’ movement, but Anna Comstock did much of the work.” She became the University’s first female assistant professor in 1899, though she held the title only briefly before some trustees objected, and she was returned to instructor status (while retaining the higher salary). “Men did not want her to have this professorship,” St. Clair says. “They were afraid if there was a female professor, people might not come to Cornell.”

In 1911, two years before she finally regained a professorial title, Anna published her landmark Handbook of Nature Study. Released by the couple’s own company (now part of CU Press), which they’d established with a friend to publish John Henry’s textbooks, it became a surprise hit. The volume, running to nearly 900 pages, is still in print. “Nature study cultivates in the child a love of the beautiful; it brings to him early a perception of color, form, and music,” Anna writes in the introduction. “He sees whatever there is in his environment, whether it be the thunder-head piled up in the western sky or the golden flash of the oriole in the elm; whether it be the purple of the shadows on the snow, or the azure glint on the wing of the little butterfly. . . . But, more than all, nature study gives the child a sense of companionship with life out of doors and an abiding love of nature.” Furthermore, she observes, “Out-of-door life takes the child afield and keeps him in the open air, which not only helps him physically and occupies his mind with sane subjects, but keeps him out of mischief. It is not only during childhood that this is true, for love of nature counts much for sanity in later life.”

Retiring from full-time teaching in 1920, Anna went on to accrue numerous accolades, including an honorary doctorate from Hobart College, inclusion on the League of Women Voters’ 1923 list of America’s dozen most outstanding women, and the naming of two Cornell buildings in her honor—a North Campus residence (which now houses the Latino Living Center) and Comstock Hall (named for both her and her husband), home to entomology and other sciences. In 1988, she was inducted into the National Wildlife Federation’s Conservation Hall of Fame.

The Comstocks’ life was upended in 1926, when John Henry suffered a severe stroke. Anna, herself ill with cancer and heart disease, spent her final years tending to him and working on her memoir, drawing from her diaries (which have since been lost). The volume might have seen the light of day in the mid-Thirties, when Herrick—the heir who received the couple’s papers—retired from the Cornell faculty and, casting about for a project, eyed the publication of Anna’s memoir as a way both to generate income and to highlight the Comstocks’ scientific legacy.

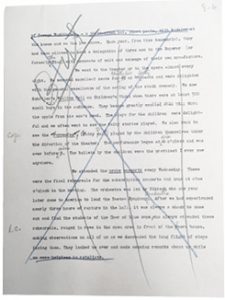

A page from her memoir’s manuscript, extensively marked up by an early readerRare and Manuscript Collections

But he abandoned the project after receiving conflicting advice from colleagues. Historian George Burr 1881 said it would be anathema to alter a personal memoir, counsel that inclined Herrick to publish Anna’s work verbatim. But Woodford Patterson 1896—the University secretary and editor of the Cornell Alumni News—panned the manuscript outright; as St. Clair writes, he considered it “too personal and trite for scholars of the Comstocks’ character.” Wielding a purple wax pencil, he chopped vast swaths of the text. “He called it ‘a desultory recital of loosely related occupations and diversions,’ ” St. Clair says, quoting her notes from the Kroch Library reading room. “He said, ‘The style of this book is repulsive; its diffuseness and disorder and aimless shifting the focus of attention all combine to make it tiresome reading.’ ” For St. Clair, those dismissive comments are infuriating. “When I found Patterson’s letter, I went on my knees on the floor in front of the card catalog,” she recalls. “I had such a physical reaction of disgust.”

Cowed, Herrick shelved the project for a decade and a half. But by the early Fifties, Patterson and others who’d expressed opinions on how to handle the manuscript had passed away, and Herrick had carte blanche to edit it as he saw fit. He wound up trimming it considerably, removing whole sections, and altering language here and there. The end result, St. Clair says, is not only that the 1953 version focuses more on John Henry’s career—unsurprising,

since Herrick idolized him—but that it squelches Anna’s distinctive voice. “She knew enough of life by the time she was seventy-three or seventy-four years old that she knew what she wanted to be recorded,” St. Clair says. “This was her saying, ‘This is what I think is important about my life; this is what mattered.’ ”

In crafting the new edition, it was important to St. Clair that readers see how Herrick had altered Anna’s prose. She and CU Press settled on some creative punctuation: the sections of Anna’s memoir that didn’t appear in 1953 are set off by scrolled brackets. “I felt that what Herrick did was for his own selfish reasons,” St. Clair observes. “He may have started off thinking he was doing it for the moral good of preserving the Comstock legacy, but I think he was trying to create something for himself.” As she notes, when Herrick did an oral history interview for the University archives in 1965, he repeatedly referred to the volume as “my book.” “It was not right,” St. Clair says of Herrick’s heavy-handed editing, “because it was not how she wanted her life and work, or her husband’s, to be remembered.”

The 1953 version of The Comstocks of Cornell ends on a heartbreaking note. After describing the diagnosis of her husband’s first stroke, Anna writes: “There are no words to describe his bravery and patience and cheerfulness after this calamity which, for us, ended life. All that came after was merely existence.” St. Clair is convinced that the ending is Herrick’s, not Anna’s, and that the actual one is among the several dozen missing pages from the original manuscript. “I don’t think that was the last sentence she wrote,” says St. Clair, who added an epilogue describing the couple’s final years. “Nobody can convince me of that. I think she had more to say.”

Three years before Anna matriculated at Cornell, Professor Goldwin Smith donated a carved bench that sits in front of his namesake building. Anna is known to have enjoyed sitting on the bench, which bears the quotation, “Above All Nations Is Humanity”; for St. Clair, doing the same offered a way to feel close to her subject. “It was important to me to sit there,” she says. “In my mind, I imagined she was sitting next to me. I felt like we were connected by a bridge through time, and I was going to set things right for her.”

Memoir editor Karen Penders St. Clair on a campus bench that Anna favoredProvided

On the Hill

In an excerpt from The Comstocks of Cornell, Anna Comstock describes life as a female student in the University’s early years

I first thought of Cornell when, during my last term at Chamberlain Institute, one of our graduates who had entered Cornell talked to me about it. He said: “It is a great place for an education; but if you go there you won’t have such a gay time as you have had here, for the boys there won’t pay any attention to the college girls.” I thought seriously and finally concluded: “Cornell must be a good place for a girl to get an education—it has all the advantages of a university and a convent combined.”

I started for Cornell in November 1874, entering at the opening of the second term. I stopped at Elmira on my way, and John Hillebrand, cousin Fidelia’s husband, came with me from there to see me settled. It was discouraging business, but we finally found a room, with a Mr. and Mrs. Harvey, in a house on East Seneca Street just below Spring Street, and a place to board with a Mr. and Mrs. Halsey in a house on the opposite side of the street.

There were then a few scattering houses on East Seneca Street above Spring, and a few on Eddy Street, but there were no paved sidewalks anywhere. Now and then there was gravel on a sidepath. I climbed up to the University as best I could, thankful that I was a country girl and accustomed to bad roads. Cascadilla Place was a forbidding-looking structure, but it housed many professors and their families and many students. Sage College and Sage Chapel were in process of building. Morrill Hall, then called South University, and White Hall, then called North University, had classrooms in their central portion but at the ends were dormitories for boys and at the top of each was a large lecture room. Of Sibley College only what is now the west section was completed.

A large wooden building occupying a place west of that given to Goldwin Smith Hall held the departments of chemistry, physics, and veterinary science. On East Avenue, President White’s house and north of it the houses of Professor Willard Fiske and Dr. [James] Law were completed. The farmhouse, with its orchards and barns, occupied nearly the place of East Sibley and Lincoln halls. There were a few old oaks and pines on the campus, but the elms were all just planted and protected by their boxes. However, it was not a bleak place, because from almost any point there was a glorious view of Cayuga Lake and the valley, lost now behind the trees.

Anna at eighteenRMC

My room at Mrs. Harvey’s looked out over town and valley; it was frankly a bedroom, and two students, William Berry 1876 and Spencer Coon 1876, had their room off the same hall. However, I was not disturbed by this, since I expected no social intercourse with gentlemen. Imagine my dismay a few days later when, answering a knock at the door, I discovered there a tall and dignified young man who evidently expected to be invited in. I stood guard firmly, while he explained that he had called to invite me to join the Christian Association. I thanked him and he retreated. Soon my neighbors called on me, and since they knew it was my bedroom, I managed in some way to express my dismay at having no other place to receive callers, but they were cheerful and seemed to think it was all right.

That night I asked Mrs. Harvey if I might receive callers in her parlor and she refused. Later she suggested that I take another small room for my bedroom, saying she would help me make my room into a study, where I might receive callers without embarrassment. When we had finished, it was an attractive room and greatly needed, for I had many callers; some women students came, but more men, naturally enough, as there were but few girls in Cornell at that time. It seemed that my boy friend of Chamberlain Institute had a mistaken idea about the social ostracism of girls at Cornell.

The days were busy and happy. We climbed up to the University through snow and slush and sometimes on ice. I made the sage observation that the native Ithacan was never self-conscious when he fell on the icy walk; he got up as well as he could, and never looked to see if someone had observed him. Not so did the recent comers take their tumbles; before they made effort to arise they looked around furtively to see who might have witnessed their humiliation. There was a steep place by Cascadilla up which, one icy morning, a South American student was carefully climbing and which I was about to attempt. Just as he reached the top he slipped and came back down on all fours, landing at my feet. I was glad I did not understand the language he was using.

When spring came there were walks in the woods after flowers for the botany, and there were boat rides on the lake, and many scrambles through the gorges. The lake was our favorite play-place. It was very different then. Two great side-wheel steamers made connections between the New York Central Railroad and Ithaca. As we paddled out through the inlet we passed many barges, some of them with picturesque families aboard, their multi-colored wash flapping in the breeze. There were small sailboats in plenty and no cottages along the shores to take away the wildness that was their charm. There was an interclass regatta that was thrilling. The seniors spilled, the juniors stopped to rescue them, the sophomores were impeded by the mishap, but the freshmen rowed manfully on and won the race.

I returned to Cornell in the fall of 1875, rejoicing that Sage College was finished. It was a beautiful home for us, and highly appreciated by those of us who had experienced the difficulties of living in town. There were two or three small reception rooms besides the large dining room, all well furnished. My room was on the second floor on the north side and very pleasant. My roommate was Minerva Palmer 1877, a beautiful Quakeress, and our companionship proved ideal. There were only thirty of us in the big dormitory, so only the first and second floors were in use.

Although we were few, college spirit was with us. Ruth Putnam 1878 came to my room one evening asserting indignantly that the freshmen were holding a meeting in a room of one of the class and she averred something should be done about it. Something was done immediately; water from a pitcher was dashed over the transom to dampen freshman ardor. But it did not work that way. They indignantly made a sortie upon us, and as they outnumbered us, there was a desperate struggle on the stairs and a rumpus in the halls which shocked everybody not in the squabble.

Anna (second woman from right) at an informal gathering in the 1890s—possibly in one of the female students’ rooms in Sage—including (behind her) Glenn Herrick, her second cousin and the future editor of her memoir.RMC

The fracas resulted in the organization of a student government association in Sage College. Julia Thomas 1875, MA 1876 (later Mrs. Irvine, President of Wellesley), was elected president and a committee appointed to make rules for our guidance. These rules, finally unanimously adopted, were not so many, but otherwise were not unlike the rules of the self-government association of today, with the exception of the one restriction that the women students should not bow to their men student friends on the campus. We were so few that it was embarrassing to recognize or be recognized in the crowds passing to and from classes. As soon as we explained to our friends the reason for ignoring them, they not only accepted the dictum, but confessed relief.

President White and Mr. Sage both thought we should have a chaperone in charge of Sage College, but we resented this and would not have it. We came to Cornell for education and had been reared to care for ourselves; chaperoning we considered insulting to our integrity. However, I must confess that some of our rules were made to govern any girl who overstepped our ideas of propriety.

We had a happy social life in Sage that first year. The gymnasium was where the kitchen now is, and was reached from the front hall via a covered porch. We had dances there every Friday night; sometimes there were girls only, but more often our men friends were invited. I remember that one evening the entire Kappa Alpha fraternity came and we had a pleasant evening, a social affair probably not recorded in the annals of that organization. I remember that one of the members made each girl with whom he danced promise to bow to him when she met him on the campus. I am sure that we all promised, but I doubt if anyone fulfilled her promise; I know I did not, although he was a nice lad. But lads, however nice, could not break our rules.

Excerpted and condensed from THE COMSTOCKS OF CORNELL: THE DEFINITIVE AUTOBIOGRAPHY, published by Cornell University Press. Copyright © 2020 by Cornell University. Reprinted by permission. Note: The book employs scrolled brackets to indicate text from Anna Comstock’s memoir that did not appear in the 1953 version; they have been removed from this condensation for ease of readability.